Waterstudio’s New Water on Shortlist

Waterstudio’s project New Water is on the Shortlist of the Urban Design WAN Awards

New development plans for Dutch flatlands

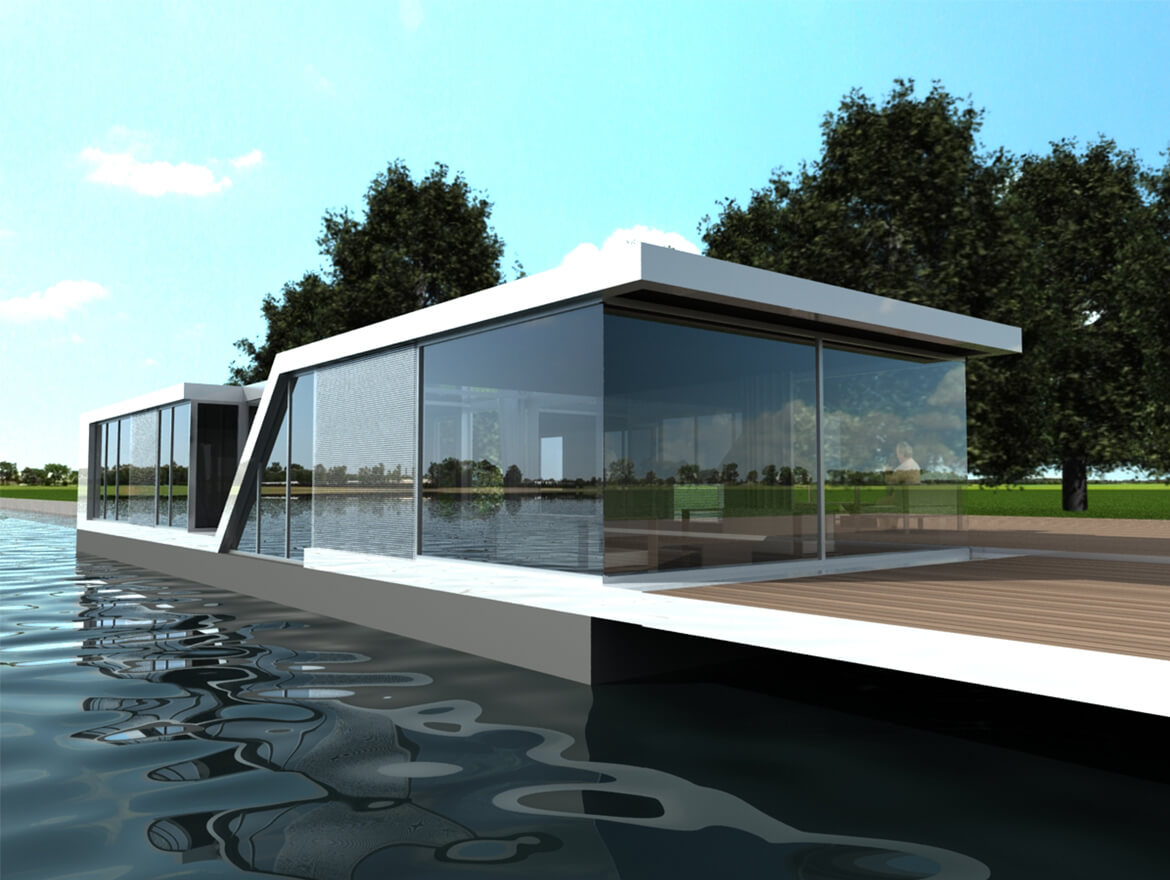

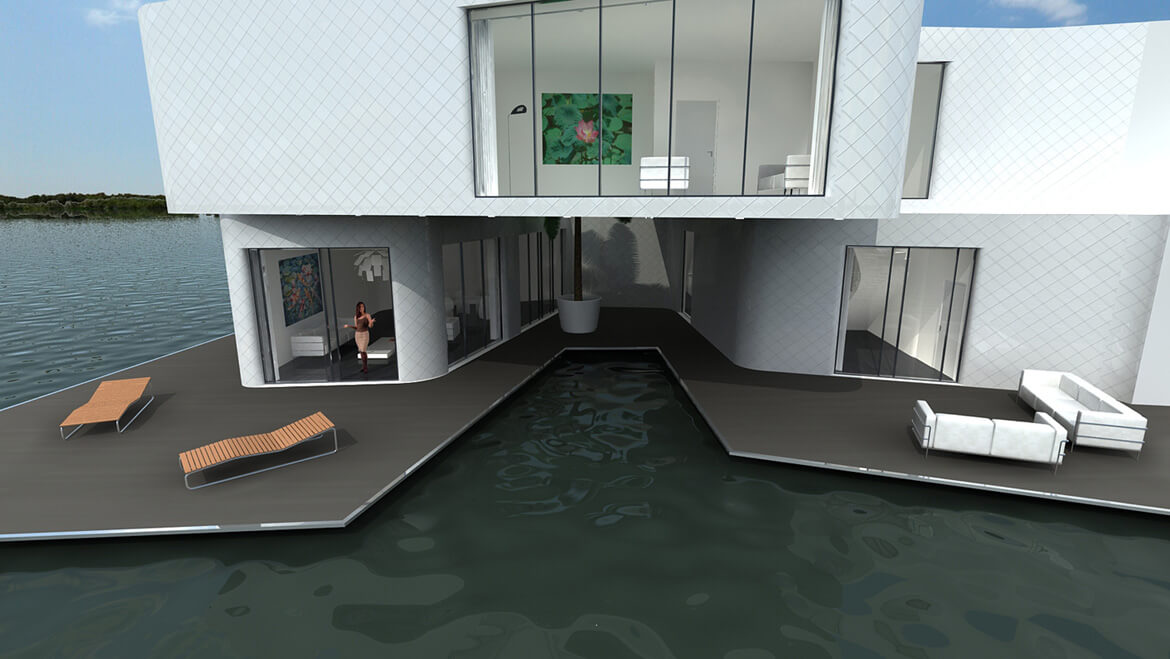

Waterstudio designed a masterplan called The New Water in which housing, ecology and water storage will be combined in a multifunctional zone. This new approach to urban development fits wet and threatened Dutch polder landscape. The client is the public-private partnership ONW consisting of the waterboard, city and bank.

The project is located in one of the lowest areas in Holland between The Hague, the beach and Rotterdam. The surrounding area consists mainly of a landscape of greenhouses which make this project a waterbased development within a sea of glass.

Almost all polders in the The Hague area are in use for greenhouses, leaving only a small amount of uncovered soil. In 1996 and 1998 large parts of this area as well as many other polders have been flooded causing enormous economical damage. The New Water masterplan consists of giving back to the water a 200 year-old artificial landscape that has been kept dry only by pumping the water out continuously. The New Water will help the surrounding polders by expanding their storage capacity in case of heavy rainfall. The ambition for this project is to set the benchmark for urban development on water in depolderised zones in Holland.

The masterplan consists of 820.000 m2 with 1200 houses of which 600 will be have a floating foundation. In this water-development project virtually all new waterbased concepts and technologies will be used; Floating houses in a row, floating social housing, large floating islands, floating roads, floating gardens, stilthouses and terphouses . The total project will be finished in 2017. Europes first floating apartment building The Citadel, measuring 90 x 140 meters, will be built in 2010.

De Volkskrant about Waterstudio.NL:

New water ‘The most concrete and advanced project in the field of living on water in The Netherlands’

Bouwen op water

Written by de Volkskrant, Wouter Keuning

Reuters about Waterstudio.NL:

‘Dutch learn to live with, instead of fight, rising seas’

Written by Reuters, Ben Berkowitz

AMSTERDAM (Reuters) – The watermark column inside Amsterdam’s city hall is more than just a tourist attraction, it’s a reminder that the Dutch capital like much of the rest of the Netherlands is well below sea level.

Some 70 percent of the country’s economic output is generated below sea level, protected by a complex-system of ancient dikes and modern cement barriers that hold back water from the sea and the multitude of rivers that weave through the country.

Now, with scientists’ predicting that sea levels will rise by about one meter (3.3 feet) this century, the Dutch are reversing centuries of tradition to create natural flood plains for rivers as well as rebuild mangrove swamps as buffers against the sea.

“We’ve been adapting for 1,000 years. That’s nothing new. It’s just that climate change is going faster than it was before,” said Lennart Silvis, the operational manager of the public-private Netherlands Water Partnership.

Instead of raising dikes, the Dutch want to reclaim land and build public recreation areas that can absorb storm surges.

Rather than dredging sand to maintain beaches, they are looking at dumping piles of sand offshore to create “sand engines” shifted by the tides. Marshes may be renewed to break the power of incoming waves.

There is even a campaign called “Room for the River” which would weaken levees to recreate natural flood plains along rivers, including the Rhine and its tributaries which flooded in 1995 following heavy rainfall that almost led to a calamity.

While the dikes can be shored up, as happened in 1995 preventing the country from being submerged in 6 meters (20 feet) of water, the dikes could collapse if the sand and clay that form the barriers absorb too much water over time.

Hence the need for a longer-term solution given the possibility the Netherlands may face sustained pressure from its rivers throughout this century as glaciers in Switzerland melt, raising the water level of the Rhine.

River discharge in the country is expected to rise 12.5 percent in the coming years. This is on top of rising levels already seen in the past 10 to 12 years.

Those who work to promote such ideas say natural water buffers are a smarter move than building higher flood walls that may not stand the test of time as sea and river levels rise.

“100 billion (euros) spent on safety alone under uncertain conditions is maybe not the wisest investment,” said Raimond Hafkenscheid, director of the Co-operative Program on Water and Climate (CPWC) in The Hague.

SWIMMING TO SURVIVE

Perhaps no country on Earth lives with rising seas in the way the Netherlands does. If the nationwide network of pumping stations failed, within a week the entire country would be covered in 1 meter (3 feet) of water.

From the age of four, virtually all children in the Netherlands start five years of swimming classes. Achieving the final “diploma” requires a test that includes treading water for half a minute, navigating an obstacle and then swimming 100 meters (328 feet) while fully dressed in heavy winter clothing.

It may sound extreme, but for Dutch families that remember the great flood of 1953, which killed over 1,800 people, wiped two villages off the map and required one of the post-war era’s largest international relief efforts, it is a small price to pay for peace of mind.

That flood, the source of the high watermark at Amsterdam city hall, drove water levels 4.5 meters (15 feet) above normal.

“A city can’t be prepared for all the change that will come but it can be flexible,” said Koen Olthuis, one of the principals of Waterstudio, a Rijswijk-based architecture firm that has designed floating structures around the world.

Fresh off a commission designing a floating mosque in Dubai, Oltenhuis is working on Het Nieuwe Water, a 2.5-kilometre wide project near the Hague that would include a series of floating apartments designed to rise and fall with the water level.

Such ideas are not new, there are already floating houses in the Dutch town of Maasbommel, to say nothing of Amsterdam’s houseboats. But they point toward the trend of living with the water, rather than trying to keep it out.

IMPLEMENTING CHANGE

The ultimate goal of the varied efforts across the country is to keep people dry while at the same time react more quickly to the threat of flooding.

The problem, some say, is that the Dutch are so confident about their existing flood systems that they don’t respond with any particular urgency when danger threatens.

“We would like to be two times faster and two times better in our decision making,” said Piet Dircke, a program manager at engineering firm Arcadis and the chairman of the Flood Control 2015 initiative.

At the IJkdijk near Groningen in the far north of the country, the group is testing a range of sensors from differet companies embedded within dikes to see if any demonstrate potential in predicting when and how a dike will fail.

But even before water hits the dikes, there are those who think it would be better to block its path in the first place.

Enter the Wadden Works, a concept for a campground alongside small lakes that would sit in front of the Afsluitdijk, a causeway built in the late 1920s and early 1930s to close off a salt water inlet of the North Sea called the Zuiderzee.

Developed by engineering and consultancy firm DHV, the Works would create a major new recreation area in the north of the country while also acting as a natural breakwater for one of the most important dikes in the world.

Almost anyone involved in water in the Netherlands will tell you without hesitation that preparation is essential as water will encroach from rising seas and river flooding due to climate change.

“We are more accepting now of the concept that nature will come, the water will rise,” said Martin Karelse, a hydraulic engineer by training who serves as a program manager for DHV.

A government commission recommended last year that the Netherlands spend an extra 1 billion euros a year over 100 years to improve its flood control. With the Dutch economy hurting from the global slowdown, few expect the mid-September budget to allocate anything close to that.

While the existing flood defenses are generally held to be adequate, the uncertainties around climate change leave those closest to the water — literally and figuratively — on edge.

“Not everything in the Netherlands is as set in place and organized as people think,” the CPWC’s Hafkenscheid said.

Dutch learn to live with, instead of fight, rising seas

Reuters, Ben Berkowitz

AMSTERDAM (Reuters) – The watermark column inside Amsterdam’s city hall is more than just a tourist attraction, it’s a reminder that the Dutch capital like much of the rest of the Netherlands is well below sea level.

Some 70 percent of the country’s economic output is generated below sea level, protected by a complex-system of ancient dikes and modern cement barriers that hold back water from the sea and the multitude of rivers that weave through the country.

Now, with scientists’ predicting that sea levels will rise by about one meter (3.3 feet) this century, the Dutch are reversing centuries of tradition to create natural flood plains for rivers as well as rebuild mangrove swamps as buffers against the sea.

“We’ve been adapting for 1,000 years. That’s nothing new. It’s just that climate change is going faster than it was before,” said Lennart Silvis, the operational manager of the public-private Netherlands Water Partnership.

Instead of raising dikes, the Dutch want to reclaim land and build public recreation areas that can absorb storm surges.

Rather than dredging sand to maintain beaches, they are looking at dumping piles of sand offshore to create “sand engines” shifted by the tides. Marshes may be renewed to break the power of incoming waves.

There is even a campaign called “Room for the River” which would weaken levees to recreate natural flood plains along rivers, including the Rhine and its tributaries which flooded in 1995 following heavy rainfall that almost led to a calamity.

While the dikes can be shored up, as happened in 1995 preventing the country from being submerged in 6 meters (20 feet) of water, the dikes could collapse if the sand and clay that form the barriers absorb too much water over time.

Hence the need for a longer-term solution given the possibility the Netherlands may face sustained pressure from its rivers throughout this century as glaciers in Switzerland melt, raising the water level of the Rhine.

River discharge in the country is expected to rise 12.5 percent in the coming years. This is on top of rising levels already seen in the past 10 to 12 years.

Those who work to promote such ideas say natural water buffers are a smarter move than building higher flood walls that may not stand the test of time as sea and river levels rise.

“100 billion (euros) spent on safety alone under uncertain conditions is maybe not the wisest investment,” said Raimond Hafkenscheid, director of the Co-operative Program on Water and Climate (CPWC) in The Hague.

SWIMMING TO SURVIVE

Perhaps no country on Earth lives with rising seas in the way the Netherlands does. If the nationwide network of pumping stations failed, within a week the entire country would be covered in 1 meter (3 feet) of water.

From the age of four, virtually all children in the Netherlands start five years of swimming classes. Achieving the final “diploma” requires a test that includes treading water for half a minute, navigating an obstacle and then swimming 100 meters (328 feet) while fully dressed in heavy winter clothing.

It may sound extreme, but for Dutch families that remember the great flood of 1953, which killed over 1,800 people, wiped two villages off the map and required one of the post-war era’s largest international relief efforts, it is a small price to pay for peace of mind.

That flood, the source of the high watermark at Amsterdam city hall, drove water levels 4.5 meters (15 feet) above normal.

“A city can’t be prepared for all the change that will come but it can be flexible,” said Koen Olthuis, one of the principals of Waterstudio, a Rijswijk-based architecture firm that has designed floating structures around the world.

Fresh off a commission designing a floating mosque in Dubai, Oltenhuis is working on Het Nieuwe Water, a 2.5-kilometre wide project near the Hague that would include a series of floating apartments designed to rise and fall with the water level.

Such ideas are not new, there are already floating houses in the Dutch town of Maasbommel, to say nothing of Amsterdam’s houseboats. But they point toward the trend of living with the water, rather than trying to keep it out.

IMPLEMENTING CHANGE

The ultimate goal of the varied efforts across the country is to keep people dry while at the same time react more quickly to the threat of flooding.

The problem, some say, is that the Dutch are so confident about their existing flood systems that they don’t respond with any particular urgency when danger threatens.

“We would like to be two times faster and two times better in our decision making,” said Piet Dircke, a program manager at engineering firm Arcadis and the chairman of the Flood Control 2015 initiative.

At the IJkdijk near Groningen in the far north of the country, the group is testing a range of sensors from differet companies embedded within dikes to see if any demonstrate potential in predicting when and how a dike will fail.

But even before water hits the dikes, there are those who think it would be better to block its path in the first place.

Enter the Wadden Works, a concept for a campground alongside small lakes that would sit in front of the Afsluitdijk, a causeway built in the late 1920s and early 1930s to close off a salt water inlet of the North Sea called the Zuiderzee.

Developed by engineering and consultancy firm DHV, the Works would create a major new recreation area in the north of the country while also acting as a natural breakwater for one of the most important dikes in the world.

Almost anyone involved in water in the Netherlands will tell you without hesitation that preparation is essential as water will encroach from rising seas and river flooding due to climate change.

“We are more accepting now of the concept that nature will come, the water will rise,” said Martin Karelse, a hydraulic engineer by training who serves as a program manager for DHV.

A government commission recommended last year that the Netherlands spend an extra 1 billion euros a year over 100 years to improve its flood control. With the Dutch economy hurting from the global slowdown, few expect the mid-September budget to allocate anything close to that.

While the existing flood defenses are generally held to be adequate, the uncertainties around climate change leave those closest to the water — literally and figuratively — on edge.

“Not everything in the Netherlands is as set in place and organized as people think,” the CPWC’s Hafkenscheid said.

Le moschee del XXI secolo

il Magazine dell Architettura

Una volta il profeta Maometto disse che il mondo intero è una moschea. Un fedele musulmano, armato di pie intenzioni, può far apparire dal nulla una moschea quasi ovunque, trasformando in uno spazio sacro una duna del deserto, una sala partenze dellaeroporto o un marciapiede della città semplicemente fermandosi a pregare. La prima moschea fu la casa in mattoni di fango di Maometto a Medina, dove un portico di rami di palma offriva ombra per la preghiera e i dibattiti teologici. Mentre la giovane religione si diffondeva, gli arabi – e poi gli asiatici e gli africani – svilupparono le loro idee su ciò che rendeva moschea un edificio. Negli ultimi decenni quello spirito innovativo si è affievolito e la maggior parte degli skyline islamici è stata dominata dal progetto composto da cupola e minareto, apparso per la prima volta secoli fa. Oggi le cose stano cambiando. Una nuova generazione di costruttori e architetti musulmani, nonché di non musulmani che progettano per gruppi musulmani, spesso in Europa o in America del Nord, sta aggiornando la moschea del XXI secolo dando vita a una fase del progetto islamico estremamente creativa, ma anche spaccata dalle controversie. Le dispute sulle moschee moderne riecheggiano i dibattiti più grandi che oggi avvengono nel mondo islamico su sessi, potere e, specie nelle comunità di immigrati, ruolo dellIslam nelle società occidentali. Persino la più semplice delle decisioni di progetto può riflettere questioni cruciali per lIslam e i suoi seguaci: le donne vanno ammesse nella sala principale della moschea o vanno confinate in zone separate? I minareti sono necessari in Occidente, dove in base alle normative sul rumore sono usati di rado per invitare alla preghiera? Che aspetto deve avere una moschea frequentata da musulmani di zone del mondo diverse? Le più audaci tra le nuove moschee tentano di rispondere a tali domande, ma sono anche efficaci dichiarazioni dintenti. «LIslam vuole affermarsi», dice Hasan-Uddin Khan, storico dellarchitettura alla Roger Williams University di Rhode Island. «Le nuove moschee dicono: Esistiamo e vogliamo che si sappia». Via via che il numero di musulmani europei aumenta – dai dodici milioni di dieci anni fa ai venti milioni di oggi – aumenta anche lesigenza di moschee. Un rapporto del 2007 del ministero dellInterno italiano ha scoperto che le moschee nel paese erano passate da 351 a 735 in soli sette anni. Anche in Francia e in Germania il numero delle moschee è esploso. Se le chiese europee restano vuote o vengono convertite in loft e scuole di lusso, i musulmani costruiscono moschee in vecchi locali notturni e supermercati, in ex fabbriche di crauti e farmaci e, ebbene sì, anche nelle chiese abbandonate. Via via che i musulmani diventano più ricchi, sicuri e geograficamente diffusi – quasi un terzo del miliardo e trecentomila totale vive in paesi a maggioranza non musulmana – ormai le moschee non sono semplici monumenti ai governanti di cui portano il nome. Sempre più di frequente simboleggiano la lotta per sposare tradizione e modernità e mettere radici in Occidente. Gli immigrati musulmani di seconda e terza generazione, che hanno sicurezza e denaro per costruire, in pietra e vetro, i simboli della forza crescente dellIslam in posti come lEuropa, sognano edifici più audaci. Limitarsi a importare larchitettura tradizionale della moschea «non esprime lealtà allambiente circostante», dice Zulfiqar Husain, segretario onorario di uninnovativa eco-moschea a Manchester, Inghilterra. La moschea che Husain contribuisce ad amministrare, in un tetro quartiere operaio di Manchester, usa legno rigenerato e pannelli solari sul tetto per alimentare il riscaldamento sotto il pavimento. Allinterno, moquette color pesca e televisori al plasma creano latmosfera di una ricca casa inglese di periferia, mentre la sala per la preghiera ha intagli ispirati alla dinastia nordafricana Fatimid del X secolo. A Singapore, Forum Architects, gli architetti della moschea Assyafaah, ultimata nel 2004, si rivolgono alla popolazione multiculturale del paese creando uno spazio esteticamente neutro, lucente e futuristico, dove possono sentirsi a loro agio sia i musulmani malesi sia quelli cinesi. Linnovazione fiorisce anche in luoghi improbabili come la Baviera meridionale. Nella città di Penzberg, lanno scorso il Forum islamico, costruito nel 2005, ha vinto il Wessobrunner Architekturpreis, un premio assegnato ogni cinque anni allarchitettura bavarese di rilievo. Semplice edificio in vetro e pietra perlacea, il Forum attira musulmani e non musulmani a entrare dalle due porte che somigliano a un libro aperto. «È un luogo di comunicazione», spiega larchitetto bosniaco Alen Jasarevic. «Ampie finestre e aperture sulla facciata, persino nella sala per la preghiera, invitano i cittadini di Penzberg a conoscere lIslam e la sua gente». Il delicato minareto, che da lontano sembra di pizzo, è una rappresentazione calligrafica delle parole dellinvito alla preghiera incise su lastre dacciaio perforato. «Non chiama alla preghiera cinque volte al giorno, ma 24 ore su 24», commenta Jasarevic. «Senza disturbare il vicinato». Le moschee e i loro quartieri, però, non sono sempre così silenziosi. Soprattutto in Europa, le moschee sono diventate lequivalente architettonico del velo: segni visibili della presenza dellIslam e quindi siti di tensione tra tradizionalisti musulmani e non musulmani. Un recente rapporto dellInstitute of Race Relations di Londra riferisce di moltissime campagne contro i progetti delle moschee in Europa. Nel 2007, una petizione che chiedeva al governo di abbandonare i piani per la costruzione di una megamoschea su un lotto di sette ettari vicino al sito dei Giochi olimpici del 2012 ha raccolto oltre 275.000 firme. Quello stesso anno, i membri della Lega Nord italiana «hanno benedetto», queste le loro parole, il sito riservato alla moschea di Padova sfilando con un maiale, lanimale ritenuto impuro dal musulmani. Un sondaggio dopinione olandese del 2004 ha rivelato che le moschee, che negli anni novanta erano state lodate come «arricchimento del paesaggio urbano», erano definite «banali», «brutte» e «imitazioni dozzinali». Un aspetto del progetto della moschea causa più rabbia di tutti gli altri: il minareto. In tutta Europa, i minareti sugli skyline cittadini sono diventati una questione politica. In Olanda Filip Dewinter, leader del partito di destra Vlaams Belang, ha criticato una nuova moschea di Rotterdam perché i suoi minareti erano più alti delle luci dello stadio di calcio della città. «Questi simboli non devono esserci», ha detto a Radio Netherlands Worldwide. Nel 2007 la cancelliera tedesca Angela Merkel ha avvertito che i minareti non devono essere «ostentatamente più alti dei campanili delle chiese». Il dibattito è vivo anche nelle comunità musulmane occidentali. «Spesso gli immigrati musulmani vogliono [un minareto], perché per loro rappresenta la moschea», dice Omar Khalidi, archivista dellAga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture del Massachusetts Institute of Technology. «Ma costano molto e, secondo altri, sono un lusso che i musulmani non possono permettersi». Per Paul Böhm, larchitetto tedesco autore della nuova moschea progettata per Colonia, i minareti sono una parte essenziale del disegno di un edificio fiero e genuino. «Secondo noi, questa struttura dovrebbe manifestare il suo intento e i minareti possono contribuire a farlo», dice. «Negli ultimi 40 o 50 anni, i musulmani della Germania si sono nascosti in seminterrati e in zone industriali [abbandonate] per pregare. [Molti tedeschi] non li hanno mai riconosciuti come parte della società. Dargli una struttura che li elevi allo stesso status [di altri gruppi religiosi] può aiutarci a capirli e ad accettarli» (cfr. Voglio togliere i musulmani dai c o r t i l i, in «Il Magazine dellArchitettura» n. 1, settembre 2007). Alcuni abitanti di Colonia, però, non sono daccordo. I membri del gruppo di destra Pro Köln hanno contestato la moschea da venti milioni di dollari perché i due minareti di 51 metri rovineranno lo s k y l i n e, ora dominato dalla famosa cattedrale gotica. I lavori procedono e gli anziani musulmani locali sperano che, una volta lì, la gente curiosi nella biblioteca, visiti la galleria darte o spenda nel centro commerciale, che Böhm immagina come «un moderno suk con latmosfera di quello tradizionale». Come molti altri architetti che disegnano moschee, Böhm si è ritrovato alle prese con il problema dellaccesso consentito alle donne nelle parti più importanti delledificio. Le moschee tradizionali tendono a nascondere le donne con pareti o tende. Negli edifici più nuovi e progressisti, le zone riservate alla preghiera per gli uomini e le donne sono spesso separate, ma uguali. Dopo tante discussioni, il comitato della moschea di Colonia ha accettato che le donne e i gli uomini preghino nella stessa sala, ma con le donne confinate in un balcone. Il progetto di Böhm è così flessibile che un giorno i due sessi potrebbero ritrovarsi sullo stesso piano. «Sono un architetto, non un politico», dice. «Ma ho aggiunto alcuni dettagli – stesse porte per uomini e donne – che lasciano spazio a evoluzioni. È un processo che richiederà tempo, proprio come nella chiesa cattolica. Mio padre ricordava le donne sedute al piano superiore, in chiesa, e gli uomini al pianterreno». Non sorprende che a spingere i maggiori cambiamenti siano le comunità di immigrati musulmani. «La moschea occidentale sta rapidamente diventando un luogo di contestazione tra i musulmani che sostengono la moschea tradizionale e quelli che vogliono far ottenere uno spazio adeguato alle donne», dice Khalidi del MIT. «La seconda generazione chiede, e spesso ottiene, quello spazio». Lo storico dellarchitettura Uddin Khan calcola che, fino a non molto tempo fa, le moschee dellAmerica del Nord concedevano solo il 15 per cento dello spazio alle donne. Negli ultimi cinque anni, lo spazio a cui le donne hanno accesso è arrivato almeno al 50 per cento. La nuova architettura e la rottura con le tradizioni cominciano a influenzare anche i progettisti dei paesi musulmani. A volte il cambiamento è un ritorno alle radici della religione. Quando ha progettato lultramoderna moschea Sakirin di Istanbul, larchitetta Zeynep Fadillioglu ha preso spunto dalla sua esperienza di preghiera nelle moschee. «Al tempo del profeta, uomini e donne pregavano accanto», dice. «Ultimamente, con lascesa dellIslam politico ovunque, le zone delle donne sono state coperte e recintate. Sono stata in moschee così e mi sono sentita molto a disagio». La zona delle donne di Fadillioglu è un ampio balcone che si affaccia sulla sala centrale, separato solo da inferriate incrociate. Una sensibilità ariosa e sfarzosa pervade ledificio. Le strutture per labluzione che precede la preghiera hanno armadietti di legno biondo e plexiglas. Nella sala principale è appeso un lampadario in bronzo da cui pendono gocce di vetro soffiato, allusione visiva al versetto del Corano secondo cui la luce di Allah dovrebbe cadere sui credenti come pioggia. Il mihrab, che indica la direzione della preghiera, è a forma di tulipano ed è turchese, «un varco che conduce a Dio», dice Fadillioglu. Dio è celebrato in modo diverso nella moschea galleggiante in costruzione di fronte alla costa di Dubai. Progettata dallo studio olandese Waterstudio. NL, il sensazionale edificio che verrà inaugurato nel 2011 assomiglia a un sottomarino futuristico che sorge dal Golfo Persico con minareti talmente bassi e sottili da sembrare periscopi. Costruita con moduli galleggianti di calcestruzzo e resina, verrà raffreddata dallacqua marina pompata attraverso il tetto, le pareti e i pavimenti. Tornando in Europa, un gruppo di giovani architetti olandesi guidati da Ergün Erkoçu volevano che lidea della loro moschea Polder fosse altrettanto elegante. Usando il concetto olandese della ricerca del consenso, il loro progetto non prevede minareti ma mulini a vento. Allinterno hanno pensato allo spazio per lhammam (il bagno turco) e una schiera di negozi. La moschea non sarebbe mai stata realizzata, ma doveva solo provocare il dibattito. Missione compiuta: gli anziani hanno detto sprezzanti che non è abbastanza tradizionale e i musulmani olandesi, ansiosi di veder espandere il ruolo della moschea al di là della preghiera, lhanno applaudita. Il progetto ha anche fruttato a Erkoçu lincarico per la moschea An-Nasr di Rotterdam, dove larchitetto sta alterando la tradizione. Il minareto di An-Nasr sarà di vetro trasparente e slanciato e non dominerà lo skyline. Linvito alla preghiera sarà diffuso dalle luci, che pulseranno al ritmo della voce del muezzin. Quando la moschea sarà finita, Erkoçu spera che i cittadini di Rotterdam vedranno linvito alla preghiera nel cielo. I musulmani guarderanno in alto e, in qualunque parte della città si trovino, volgeranno il pensiero alla preghiera.

Citadel in ABC’s list of bizarre buildings

Together with buildings from Gehry and Hundertwasser, Olthuis’ Citadel is mentioned in ‘Worlds most bizarre structures’