By Erik Bojnansky, BT Senior Writer

Biscayne Times

volume 15 issue 1

Photo Credits: Waterstudio

IT MAY SOUND CRAZY TODAY, BUT DESIGNERS AND ENGINEERS AROUND THE WORLD ARE ALREADY EMBRACING LIFE ON THE WATER

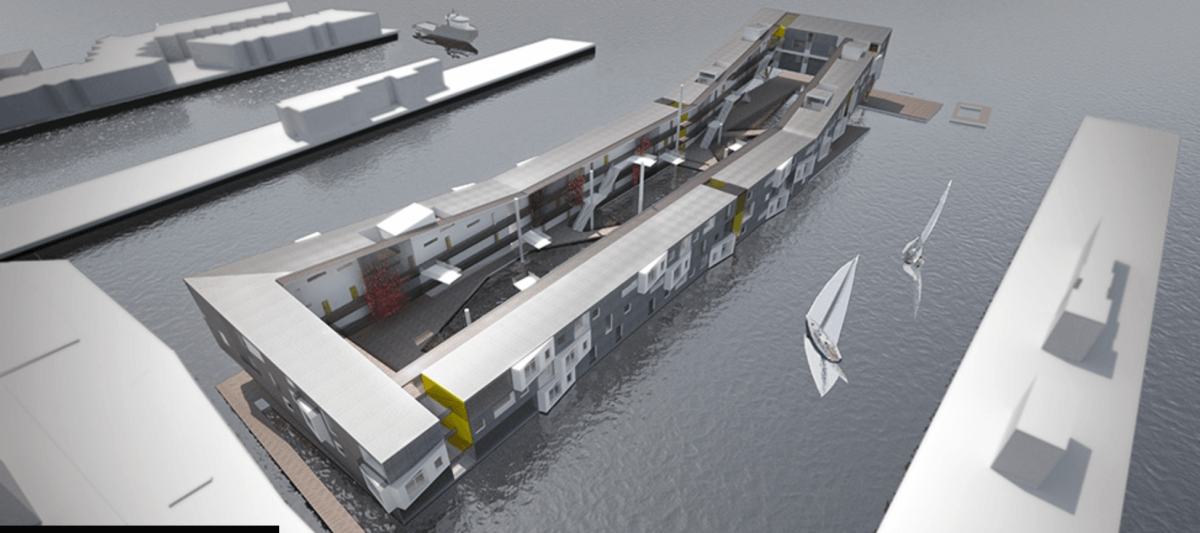

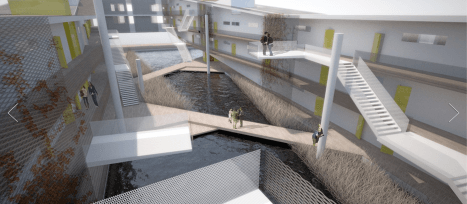

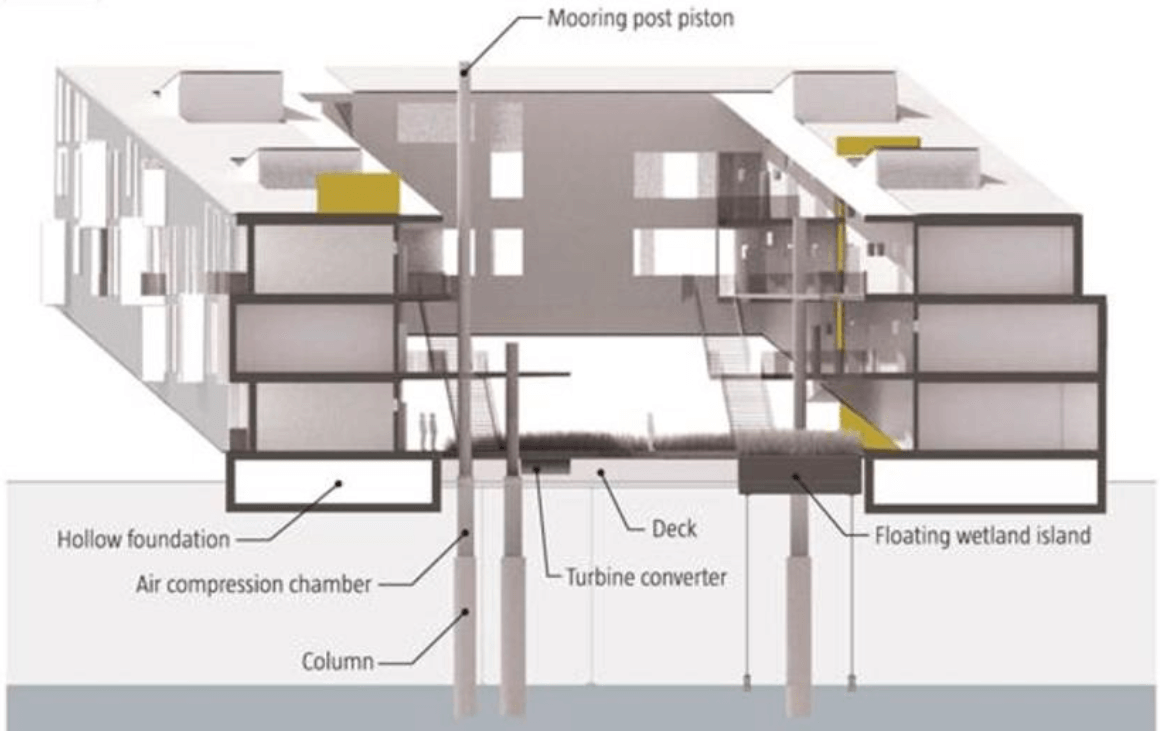

For more than 14 years, Dutch architect Koen Olthuis has been designing buildings that float. His portfolio includes the construction of 200 floating homes and offices in the Netherlands.

Later this year, luxurious floating islands designed by his Rijswijkbased architecture firm, Waterstudio, will be shipped from the Netherlands to Dubai and the Maldives. Olthuis is also experimenting with floating computer classrooms and other facilities called City Apps that he hopes will soon be transported to floodprone Bangladesh. And he’s in contact with a New Jersey developer who wants to transform the Lincoln Harbor Yacht Marina into a floating residential community with views of the Manhattan skyline.

Olthuis has other ambitious ideas, too. On his architecture firm’s website, www.Waterstudio.nl, you’ll find plans for floating apartment buildings, floating restaurants, floating hotels, floating cruise ship terminals, floating places of worship, floating beaches, floating golf courses, floating “sea trees” for animals, floating facilities (City Apps) for flooded slums, and floating islands for he very wealthy.

“When we started in 2003, we were the only office that was 100 percent into floating structures,” says Olthuis. “Everybody said we were crazy. But we saw the market, and today there are many, many architects working on floating structures in Holland and in Europe. It has become more mainstream.”

Olthuis also wants to bring his designs to Miami’s urban areas and show that water, especially in the form of rising sea levels, doesn’t have to be an obstacle to future development. It can be an asset.

“The reason I’m an architect is that our cities are not perfect. They don’t function as well as they should,” says Olthuis, who floats his structures on concrete box foundations filled with Styrofoam. “I think that water is the next ingredient to improve the performance of cities.”

Rising seas pose a major threat to Greater Miami. Within the next 80 years, climate change may result in ocean levels that are up to seven feet higher than today, washing out huge sections of flat Florida. But Olthuis feels his floating structures can literally rise to the challenges that tides could bring in the coming decades. And for the present, he argues, floating neighborhoods can provide greater flexibility for urban planners, especially in places like Miami and Manhattan, where vacant land is scarce and expensive.

So far, Miami has not taken well to his plans. His idea to create a floating Major League Soccer stadium for David Beckham in downtown Miami didn’t sail. And his proposal to build a floating parking facility for the American Airlines Arena ran aground.

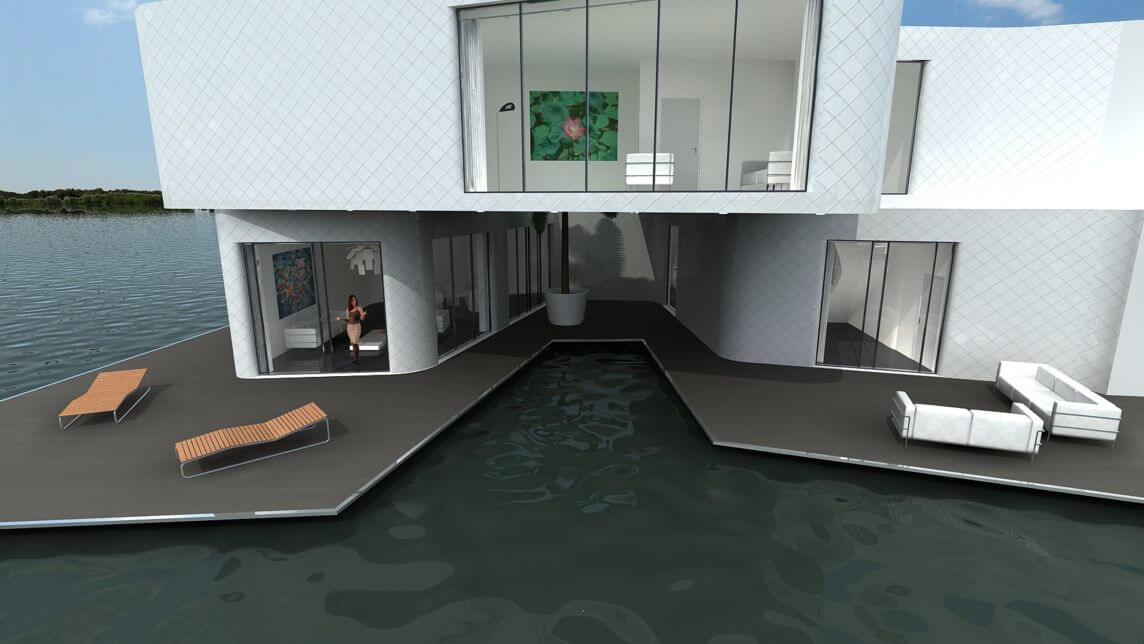

And then there is Maule Lake, a privately owned body of water in North Miami Beach bordering the upscale neighborhood of Eastern Shores. Business associates of Olthuis, through the Dutch Docklands Company, were contracted to buy the lake. It’s here that Olthuis planned to anchor 29 artificial islands each about 7000 square feet, with a fourbedroom house, vegetation, swimming pool, and a couple of boat docks and sell them for $12.5 million apiece. A 30th island, called an “amenity island,” was to feature a clubhouse. The floating community would be called Amillarah. (The project is named after another Dutch Docklands venture, Amillarah, in the Maldives. The word amillarah means private island in Maldivian, according to Dutch Docklands.)

Many Eastern Shores homeowners were horrified at the thought of 30 private islands being built in what they considered their backyard. Among their fears: that the islands would become projectiles during powerful hurricanes, that they would ruin the aesthetics of the neighborhood, and that they would attract throngs of gawkers.

“We don’t want it. We’re going to fight against it. And we’re not going to let it happen,” said Chuck Asarnow, president of the Eastern Shores Homeowners Association, in an interview with the BT in May 2015. In response to the outcry, the North Miami Beach City Council (four members of which, including Mayor George Vallejo, lived in Eastern Shores) declared Maule Lake to be a “conservation area” in July 2015, thus prohibiting development.

But Amillarah in North Miami Beach may not be dead in the water. This past October, Scott Weires, an attorney representing Raymond Gaylord Williams, the owner of Maule Lake, sent North Miami Beach officials a letter announcing his client’s intention to sue under Florida’s Bert J. Harris, Jr. Property Rights Protection Act for $37 million in damages if the city doesn’t rezone the lake. Maule Lake, incidentally, was a rock quarry used by the Maule Rock Mining Company, run by E.L. Maule, in the early 20th century. Williams is a descendant of Maule.

Under the Harris Property Rights Protection Act, a private property owner can seek relief when a governmental body imposes restrictions on the use of that property.

In a February 2, 2017, memo to NMB officials, city attorney José Smith stated that the Williams claim “lacks both merit and validity,” and that the law firm of Weiss Sorota Helfman had been retained to represent the city. Eastern Shores residents remain defiant, insisting that there were never any rights to build on the lake because it was never zoned for development.

“That took them awhile. I thought it was over,” says Fortuna Smukler, chair of the Eastern Shores Crimewatch committee, regarding Williams’s filing of a Harris action 18 months after the city designated the lake a conservation area. “I have confidence in our city attorney. He originally said that Williams won’t have a claim, and I believe him.”

Adds David Templer, an attorney and board member of the Eastern Shores Homeowners Association: “It’s pretty interesting that we use up all the waterfront land [for development] and, hey, now we can use up the water, too.” Weires contends that Williams has the right to develop the lake he has inherited, or to sell it with the development rights attached.

“Our investigation has revealed that these privately owned lands are not environmentally restricted and were never properly zoned by the city,” Weires tells the BT. “As a result, we contend that our client has a constitutional right to develop the entire parcel any way he wishes.

“That said,” Weires continues, “our client has always been, and continues to be, open to discussing possible resolutions with the city that would allow for the reasonable development of some portion of the 117 acres, while maintaining a large amount of the open water.”

And Olthuis? He’s still interested in building floating homes for Maule Lake. It will be a chance to showcase his buoyant residences, designed to withstand the strongest hurricanes, as an environmentally friendly method of developing submerged real estate.

“Miami can test these kinds of floating structures in order to use them on a bigger scale in the near future,” he says.

Olthuis isn’t the only person seeking to build innovative structures directly on the water. There are a number of bold designs floating around.

Among those proposing plans is the Californiabased Seasteading Institute, a nonprofit organization that received significant early funding from libertarian by Libertarian billionaire Peter Thiel “to provide a machinery of freedom to choose new societies on the blue frontier.” This past January, the Seasteading Institute signed a memorandum of understanding with the French Polynesian government that aims to build the first phase of a selfsustaining, floating village within the territorial waters, which would also have its own Special Economic Zone and “unique governing framework.”

The village, estimated to cost between $10 million and $50 million, is being designed by Blue 21, a Dutch engineering firm that also specializes in building floating structures. It will be constructed by Blue Frontiers, a forprofit company spun off from the Seasteading Institute. Not to be confused with the nonprofit marine conservation group Blue Frontier Campaign, the Seasteaders’ Blue Frontiers aims “to develop and construct floating islands and to operate the seazone.” The institute envisions thousands of seasteads “across French Polynesia, the Pacific, and the world” that would “test new ideas for government.”

Doug Pope, a Jacksonvillebased shipwreck treasure hunter, also wants to jumpstart plans to create his project, Oceana Water Resort, a 50unit hotel sitting on an elevated platform and rising six stories above the Gulf of Mexico, 16 miles northwest of Key West. It would be situated in water 5560 feet deep, he told the Miami Herald in February, and sit on pilings that could be raised and lowered as needed. Oceana, Pope declares, will be designed to withstand winds up to 200 miles per hour and will be powered by generators in concert with wind and solar power.

And in Riviera Beach in Palm Beach County, Fane Lozman, a former outspoken North Bay Village activist, wants to build stateoftheart stilt homes capable of responding to the tides, on 25 acres of prime submerged real estate that’s just a few miles from President Donald Trump’s MaraLago.

Steve Israel, a real estate investor and developer, says Mother Nature inspired his desire to turn Lincoln Harbor Yacht Club in Weehawken, New Jersey, a marina he has owned for 25 years, into a floatinghome community.

“Hurricane Sandy flooded everything around us, including things that were anchored on the ground,” Israel recounts. “But all my boats floated up. We have high pilings and no damage.”

Olthuis has already designed a “doublestory floodresistant yacht” without motors that can serve as floating homes for Lincoln Harbor. But because New Jersey bans stationary houseboats, Israel is also seeking someone who can build luxury “livable yachts” with engines and limited mobility at least until the houseboat law is overturned.

“This is what I am mostly excited about,” Israel says, touting the marina’s views of Manhattan and

proximity to a New JerseyNew York ferry. Israel sees this as an opportunity to destroy a nationwide stigma against houseboats, and a means to prepare for a wetter future. “Both cities [New York and Miami] are likely to be flooded in the near future,” he says. “Why assume that the places we live have to be anchored to the ground?”

If his Lincoln Harbor venture works out, Israel may try something similar for the marina he’s redeveloping in Fort Myers near the site of a future 18story condo he may codevelop or sell to another investor. (The proposed condo has parking on the first three floors, Israel says, partly as a precaution against future flooding events.) Israel would also love to set up a floating community in Miami: “I do believe Miami is very ripe for the same kind of deal.”

Building directly on the water isn’t a new thing. There’s Olthuis anticipated a parking crunch with this structure floating next to American Airlines Arena.

evidence that people have lived in stilthouses on the shores of lakes and seas since prehistoric times. And there have been floating villages in Asia for centuries.

In Florida, the waterways of Miami and Miami Beach were once filled with houseboats, says Paul George, a historian affiliated with the HistoryMiami Museum, and a “It kind of evolved,” George says, noting that the first houseboats on the Miami River, in the 1920s, were anchored near Grove Park in today’s Little Havana. “My sense is that some of these people were Northerners,” he says. “They were staying on houseboats, staying during the season, which is wintertime in Miami.” By the 1930s and 1940s, there were hundreds of houseboats on local waterways.

By the 1950s and 1960s, houseboats were also tied to docks in Miami Beach and North Bay Village, inspiring a television show in the early 1960s called Surfside 6, about a detective agency based on a houseboat moored across the street from Miami Beach’s Fontainebleau Hotel.

Just off of Key Biscayne, in the shallow waters of Biscayne Bay, another aquatic community sprouted, called Stiltsville. Its origins can be traced to 1933, when Crawfish Eddie Walker turned a wrecked ship into a spot where he could sell chowder and bait to recreational fisherman. “He was a great storyteller,” George says.

Within a few years, Walker had neighbors. Various clubs, restaurants, lodges, and weekend homes were established, either on grounded ships or in stilt houses that rose ten feet or more above sea level.

At its height there were 27 houses and converted shipwrecks in Stiltsville. But the community’s structures were gradually weeded out by hurricanes. Prior to Hurricane Betsy in 1965, there were 24 businesses operating on old ships and stilthouses, notes George. After Betsy there were just 17.

Permits for new structures stopped after Biscayne National Park took over Stiltsville in 1980. The businesses and residences that remained were allowed to operate another two decades. Then along came Hurricane Andrew, which whittled the houses down to seven. After a campaign was launched to save the structures, the remaining seven houses are now shuttered, preserved relics that are maintained by their former owners, now referred to as “caretakers.”

Hurricanes slashed the number of houseboats in Miami and Miami Beach, too. That and a growing stigma toward houseboats. Some of the vessels on the Miami River became unsightly hunks of junk. George says the houseboat dwellers were often referred to as “river rats.” By the 1980s and 1990s, the City of Miami was outlawing them on the Miami River and other waterways. Miami Beach passed similar legislation. And marinas? They started turning away houseboats and other vessels used as fulltime residences.

It’s thanks to Fane Lozman that Dutch Docklands now has some added legal support in its pursuit of the Maule Lake project. Lozman, the creator of Scanshift, a software program that keeps tabs on the stock market, fell in love with the Miami houseboat lifestyle more than a decade ago and fought all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court for his right to continue living on one.

Lozman has a reputation for fighting. In 2003, when his first houseboat was tied up in North Bay Village, he tangled with Al Coletta, a politically influential property owner who allegedly threatened Lozman when he asked if a ramp could be provided for a disabled elderly houseboat owner.

Soon Lozman was fighting Coletta’s allies at North Bay Village City Hall. In November 2003, Commissioner Robert Dugger was arrested for official misconduct based on evidence Lozman collected showing that Dugger failed to disclose his financial connections to Coletta. The Seasteading Institute hopes to build a floating city in French Polynesia, like this concept designed by Blue21.

In April 2004, police Chief David Heller resigned and Mayor Al Dorne and Commissioner Armand Abecassis were arrested for actions related to an obscene threatening cartoon left anonymously in Lozman’s mail.

Lozman might still be in North Bay Village if it hadn’t been for Hurricane Wilma in October 2005. His houseboat survived, but 41 of the neighboring houseboats sank, and the marina where he docked was destroyed. In the aftermath, he discovered that many marinas were reluctant to accept houseboats for fear of turning them into “aquatic trailer parks.”

The only place that would accept Lozman’s houseboat was a marina owned by the City of Riviera Beach, 75 miles up the coast from North Bay Village. Within two months of relocating, Lozman learned that the city planned to condemn the marina as part of a controversial $2.3 billion waterfront redevelopment plan. Lozman sued to stop the project. Riviera Beach officials responded by claiming that Lozman hadn’t paid his dock fees, an accusation he denied. In 2009, after a circuit court judge ruled that his motorless houseboat was a “vessel,”

Riviera Beach officials seized his houseboat under admiralty law, towed it away, and destroyed it. Lozman, in turn, appealed the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 2013, the court ruled that Lozman’s houseboat was, indeed, a home and not a vessel.

Although Lozman says he’s still litigating to be compensated for his home’s destruction, it was his case that has helped Koen Olthuis’s Dutch Docklands associates argue that the proposed floating islands in Maule Lake will be, in fact, floating properties. Lozman bought another houseboat, a circa1967 twostory home that was once featured in a Frank Sinatra crime drama called Lady in Cement. Unable to find another marina, he kept it anchored in Biscayne Bay near in the 79th Street Causeway.

Then in 2014, he was contacted by the owners of 200 acres of submerged property on the Intracoastal Waterway, along A1A in Singer Island, a narrow strip of land that is now the most affluent part of Riviera Beach.

“They were wealthy people whose family was paying taxes on it for the past 94 years,” Lozman says. The family was so enamored of his “David versus Goliath Doug Pope’s vision of his Oceana Water Resort, a 50unit hotel 16 miles northwest of Key West in the Gulf of Mexico. story,” as Lozman puts it, that they offered to sell him 25 acres of their submerged land for $250,000. The deal closed later that year.

By the summer of 2016, Lozman had triumphantly towed his second floating home, the Sinatra houseboat, adorned with a banner proclaiming his Supreme Court victory, and anchored it at one of his submerged land parcels. Lozman also announced his intention to build a community of floating homes on his 25 acres.

His waterfront condo neighbors, who lived along A1A, were less than thrilled. Last July, Singer Island residents, fearful of losing their views and property values, petitioned the Riviera Beach City Commission to not grant Lozman street addresses.

Lozman says his neighbors’ expressions of dismay weren’t limited to petitions or pleas to local media. A couple of men in a boat tried to hit him with a drone, Lozman recounts, and someone broke into his houseboat and left garbage bags filled with feces.

“One woman came over and tried to buy my property,” Lozman remembers. When he said no, “she started cursing at me. She wouldn’t take no for an answer.” (Emails to the Singer Island Homeowners Association, as well as calls to the association’s president, went unanswered by deadline.)

This past August, Lozman’s Sinatra houseboat sank. The cause isn’t known, but Lozman says the fact that a door to the second floor of his houseboat was open, and that several hatches were missing, indicate an intruder may have sunk it. Witnesses also saw people with flashlights near his property prior to the sinking, he adds.

In spite of his best efforts, the home couldn’t be salvaged. The matter is under investigation and Lozman now lives with his girlfriend at an undisclosed location.

Despite the setback, in November Lozman won yet another case, this one forcing the City of Riviera Beach to give him street addresses for his properties, enabling him to obtain permits from the city, state, and Army Corps of Engineers.

Lozman has since changed his mind about creating a community of floating homes in Riviera Beach. Instead he wants to create Tidal House at Renegade, a development of 40 or 50 twostory stilt homes that use a pinion gear system to move with the tides, plus aerodynamic roofs that can withstand high winds.

Terry and Terry Architects, a San Francisco firm run by brothers Alex and Ivan Terry, came up with the design that, Alex Terry tells the BT, was unveiled at an architecture exhibit in Venice, Italy, last summer and is based on exploratory oil rigs.

“They’re kind of a response to changing climate and a lot of issues with tidal action…and places where there is severe storm action,” Alex Terry says, adding that the Tidal House design has also garnered interest in India.

“The stilt home is a superior solution,” says Lozman, who has hired contractor Donna Milo, a former Upper Eastside resident (and onetime Miami City Commission candidate) to build the homes. Lozman hopes to start construction by 2018, adding that he’s already had offers to buy Tidal House residences for $3 million each.

“In Palm Beach County, three million is not a lot of money,” he notes, pointing out that the condos on Singer Island sell for as much as $10 million.

Wayne Pathman is an environmental and landuse attorney. He has served on special committees on sea level rise for the City of Miami and MiamiDade County, and is chairman of the Miami Beach Chamber of Commerce.

Pathman advocates for extensive changes in urban codes and infrastructure improvements to address the threat of rising seas. He supports actions spearheaded by Miami Beach Mayor Philip Levine namely, adding pumps and elevating streets to handle flooding.

Pathman has advocated against creating new historic districts in the city’s North Beach neighborhood, arguing that doing so would limit options for property owners in the future, as tidal events become more pronounced. Pathman often reminds people that the insurance industry is already looking at the future impacts of sea level rise in Florida.

But placing floating homes and stilt houses on South Florida’s waterways? “I don’t think people here in South Florida are really ready for floating homes like other parts of the world,” he says. “It has to be explored when sea level rise becomes more of an impact.”

Miami Beach, in particular, has been pretty tough on even common boats anchoring on the city’s waterways, this in response to waterfront homeowners who complain that liveaboards (full time boat residents) invade their privacy. Although a proposed law making it illegal to live aboard a boat fulltime was rejected in 2002, the city has recently passed laws forbidding vessels from anchoring in public waters without permission, except for specified areas near the Venetian Causeway.

Dutch architect Olthuis emphasizes that Maule Lake has been privately owned for decades, and he is sure the Amillarah project would be beneficial to the surrounding neighborhoods and the city itself. He points out that the Supreme Court ruling in Lozman’s case clarifies that floating homes without motors are actually homesteads that can be taxed as property. In other words, floating homes can provide cities with revenues.

Olthuis argues that places like South Florida need to start thinking seriously about how climate change will affect living choices.

“You can see that cities like Miami and New York and Guangzhou are the top cities being threatened by sea level rise, in terms of assets,” he says. “Miami has to come up with different kinds of solutions. You have to come up with new technology, and you have to change the DNA of cities. You have to slowly start implementing these kinds of developments that have growing resiliency.”

He’s hopeful that building codes in Florida will soon force developers to build in preparation for a changing environment, much like in his native Netherlands. “In 10 or 15 years, builders will, for the most part, have made the switch to resilient typologies like floating houses or stilt houses in Miami,” he predicts.

Other aspiring builders, like Doug Pope in Jacksonville, think the new administration in Washington will be their ally in removing regulations. A single regulation dealing with Oceana’s water treatment stood in the project’s way when it was proposed in 2010, Pope asserts. Then the project fell into limbo when Oceana’s financial backers suddenly balked. Now he is somewhat confident he can find new investors to raise the $26 million needed to build Oceana.

“Things are looking better,” he says. “I wouldn’t say ‘good.’ I would say better.” But why submit yourself to outside governmental regulations at all? Joe Quirk, a science author affiliated with Peter Thiel’s Seasteading Institute, says technology can innovate more quickly if entrepreneurs don’t have to report to government. That’s why the Seasteading Institute wants to create floatingisland “startup societies” with their own autonomy.

If the French Polynesia pilot project succeeds, notes Randolph Hencken, the institute’s executive director, he can envision “future seasteads in places like Miami and Bangladesh.” Says Quirk: “In order for us to bring this technology to Florida or Miami, the governments of Florida and Miami would have to legislate us some measure of legislative or regulatory autonomy.”

Absent new discoveries that could clean the atmosphere of greenhouse gases, the oceans will continue to warm and rise increasingly faster as ice from Greenland and Antarctica slips beneath the waves, predicts Harold Wanless, chairman of the University of Miami’s Department of Geology and an outspoken climatologist.

Because humans have been burning fossil fuels for more than a century, Wanless points out, the planet has about as much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere today as it did 3 million years ago, a time when there were no polar ice caps and the oceans were 80 feet higher. “This isn’t a cloud of smoke that will just evaporate,” Wanless quips.

The UM professor adds that we won’t have to wait until 2100 to see the full effects of sea level rise. In less than 30 years, he says, tidal flooding will be significantly worse for lowlying areas like Broward, Miami Beach, Key Biscayne, west MiamiDade, south Brickell, and Miami’s Edgewater and Upper Eastside neighborhoods, along with other areas up and down the Biscayne Corridor. (For more on sea level rise projections, see “Six Feet Under,” June 2015.) According to Wanless, Miami Beach’s expensive efforts to mitigate rising seas will only last a couple of decades.

Wanless says the innovations proposed by Olthuis, the Terry brothers, and the Seasteaders are “nice” and “creative,” but he questions if anyone is going to want to live in a flooded area that will be significantly hotter, ravaged by more powerful storms, and difficult to traverse.

A better idea, Wanless suggests, would be preparing places like Omaha, Nebraska, to accommodate the millions of people who will be displaced from coastal communities in the United States.

Olthuis, however, is undeterred. He’s confident his floatingstructure designs can help South Florida adapt to the changes that most scientists agree are certain to come. And in addition to Maule Lake, he has leads on other sites.

“You can imagine that other people with new opportunities have contacted us,” he says. “Developers who are asking if we can do the same for their water.” Olthuis wouldn’t identify those developers or where future floating projects might be located.

“They’re not ready,” he explains. “They must get hold of all their licenses and all their agreements before they start bringing their projects into the open.”

Click here for the full article in pdf

Photo by Roos Aldershoff, courtesy of Marlies Rohmer Architects and Urbanists

Photo by Roos Aldershoff, courtesy of Marlies Rohmer Architects and Urbanists Photo by Marcel van der Berg

Photo by Marcel van der Berg