World’s first floating apartment build to commence in 2014

Gizmag, Phyllis Richardson, October 2013

The Dutch are known for their ingenuity in taming it and using it to their advantage, but their systems for keeping water at bay are now being rethought by architect Koen Olthuis and his team at Waterstudio. While rising sea and river levels have inspired governments around the world to invest in better flood defenses, with the Citadel, Olthuis is embracing water-borne housing with particular vigor.

The Dutch are known for their ingenuity in taming it and using it to their advantage, but their systems for keeping water at bay are now being rethought by architect Koen Olthuis and his team at Waterstudio. While rising sea and river levels have inspired governments around the world to invest in better flood defenses, with the Citadel, Olthuis is embracing water-borne housing with particular vigor.

Designed for developer ONW/BNG GO, The Citadel is a flotilla of apartments in one modern luxury development. The project, which will begin building work early next year, will consist of 60 units in a high density arrangement (30 units per acre of water). Part of the project means halting some flood defenses and letting the water back in. Olthuis points out that Holland has as many as 3,500 polders (patches of low-lying land that are protected by artificial dikes) which are below sea level and kept dry by pumping water out 24/7. This new development, dubbed New Water, will essentially be re-flooded after centuries of being kept artificially dry.

Lightweight construction on top of a main deck and easy connections to land are part of the program designed to deliver the same level of comfort as in a high-rise building. A large, heavy, floating concrete caisson provides the foundation, which also contains the car park, and will support the apartments. These will consist of 180 modular elements, all arranged around a central courtyard.

Construction will take place in a temporary dry dock. When construction is completed, explains Olthuis, the pumps will stop and the site will flood. Once the site has been “depolderized,” the Citadel will float in 6 feet of water, which will later rise to 12 feet in depth. A floating bridge will connect the Citadel to the mainland, allowing residents and emergency vehicles access. The architects maintain that due to the large size of the overall concrete caisson base, which is 240 x 420 x 9 feet in size, residents will not be able to detect any water-related motion.

Though this is partly a government-funded enterprise, this is the higher-end part of the development and the design of the units is quite bold. The apartment blocks are made up of irregularly shaped floors stacked at odd angles to one another so that overhangs alternate with shaded window recesses. Each has its own floor plan and outdoor space.

Sustainability is an abiding concern, though the Citadel does not seem to have yet committed to the full range of technologies. The facades will be clad in aluminum, as its longevity and low-maintenance requirements were found to outweigh its energy costs. Greenhouse units and green roofs will be part of the environment but it is not yet clear how extensive these will be. Energy saving methods and technology are estimated to make consumption for the Citadel 25 percent less than that of a conventional building on land. Not surprisingly, all of the apartments will have water views and most will have their own berth for a small boat. The Citadel is part of a larger development that will be built in this depolderized zone of New Water, which will eventually have 6 such floating apartment buildings.

Dutch firm says giant floating platforms could ease urban crowding

South China Morning Post,Jamie Carter, November 2013

There has been much debate on where land can be found to house a growing population in Hong Kong. For communities elsewhere, the need is even more pressing.

With global population density increasing and sea levels expected to rise by as much as 30cm by 2050, many coastal habitats will come under intense pressure. And the answer could be right on the horizon.

“In major cities there’s already a lack of space and the next logical step is to make use of water,” says Koen Olthuis, founder of Netherlands-based Waterstudio.nl and architect of multiple maritime projects.

“It’s just evolution – the elevator made vertical cities of skyscrapers possible, and water is the next step for letting cities grow and become more dense.”

More than two-thirds of the Netherlands is prone to flooding, and much of it is below sea-level, which gives its architects and engineers an unusual perspective on man’s relationship to water. While he stops short of proposing giant cities at sea, Olthuis thinks the definition of a city should be changing constantly.

Waterstudio.NL’s City Apps project tackles urban density and climate change. It was inspired by Olthuis’ belief that cities should be more flexible, and approached as a product.

“Smartphones all look the same but they are not, they are personalised with different apps,” he says. “We looked at cities and saw they have their own problems, and our floating City Apps simply add to the hardware of a city.”

Waterstudio’s first project is for the watery Korail slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh, where 70,000 people struggle to survive. Its solution – a small floating platform housing a school with 20 iPads fixed to the walls, intended to be used as an internet hub at night – has mostly been built in the Netherlands.

“In slums there are no rules – if you build a house it can be destroyed in a few months by the government rethinking that area, but if that happens then City Apps can be moved,” says Olthuis. “We’ve put the floating platform in Dhaka. We need 14,000 plastic PET bottles to keep one City App floating, so we got the local people to collect the bottles and paid them four to six cents each.”

The next City App – this time for sanitation – is planned for Bangkok.

A similar project comes from NLE, another Netherlands-based architectural practice, which has been working with the floating community of Makoko, near Lagos in Nigeria.

Around 100,000 people are thought to live here in stilt houses – largely as a result of massive urban sprawl – but the community lacks schools and infrastructure. NLE’s solution is a pyramid-shaped primary floating school built from local bamboo, which is intended as a community hub.

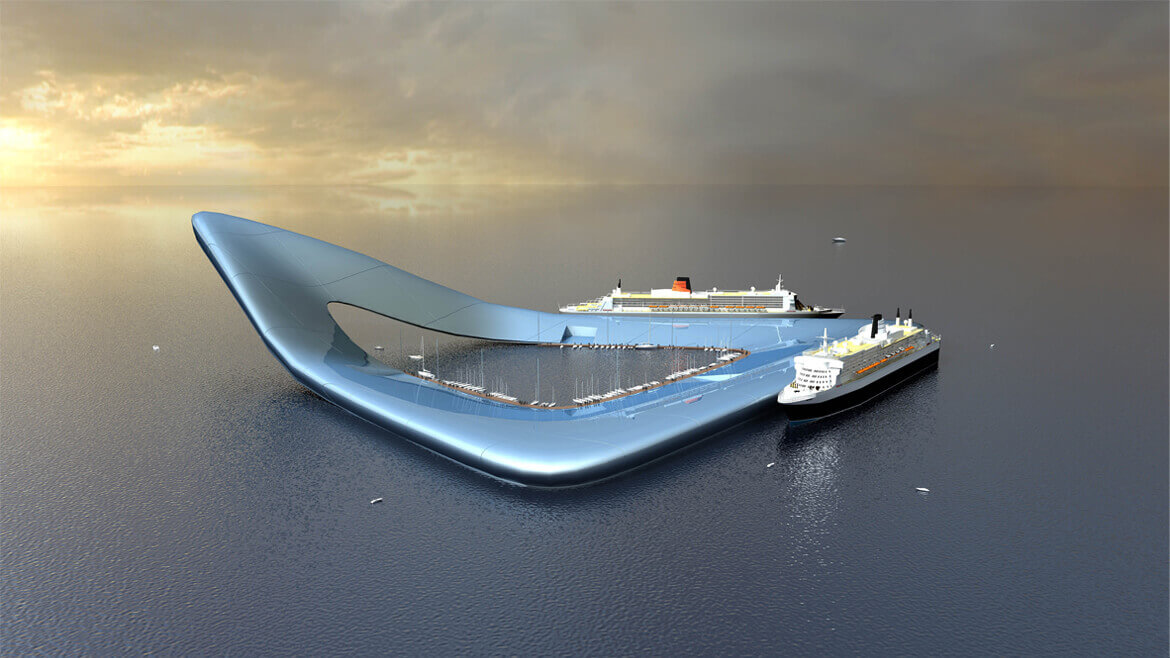

Such socially progressive projects are often spin-offs of lucrative contracts elsewhere. Waterstudio’s Five Lagoons Project, a joint-venture between Dutch Docklands and the government of the Maldives, will see an area of about 740 hectares supplied with luxury floating developments.

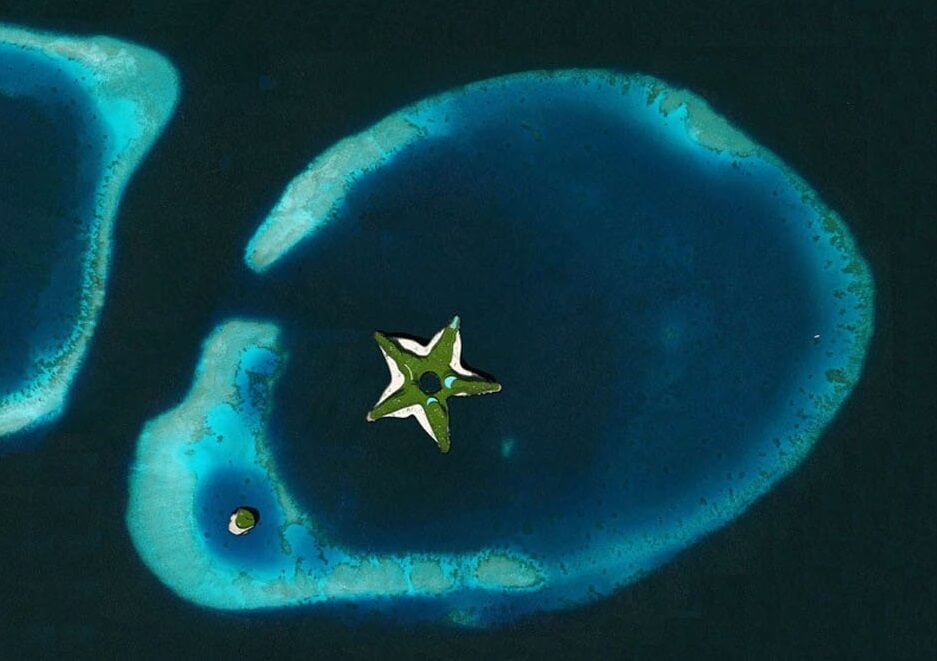

“We are going to develop five lagoons with different functions, including a resort, a conference hotel and a floating golf course,” says Olthuis, though the point of the star item – a luxury Ocean Flower resort of 185 villas – isn’t just to tempt tourists.

“By doing this we will learn how to make big green islands, and see how we can then make social housing on the water for local people,” says Olthuis.

His long-term goal is to help the 110,000 people in the Maldives’ capital city Malé, which is barely 1.5 metres above sea level and likely to be submerged in the next 85 years.

“You need this kind of expensive project to fund the future projects to help society,” Olthuis says.

Next up is Miami, where 17 floating developments will be built on a large lake. Floating communities aren’t always a response to rising sea levels in coastal communities. Non-profit organisation the Seasteading Institute wants to initiate an autonomous offshore community that pushes total freedom and encourages innovation and experimentation beyond the reach of governments.

“We’re looking for trailblazers,” says the organisation’s promotional video. “We believe humanity needs a new, blue frontier where we’re all free to explore new ways of living together.”

It claims “seasteaders” would only need the kind of money required to live in a big city. The institute is now attempting to raise money for its Floating City project on crowd-sourcing website Indiegogo, and doing fairly well – though it also needs a “host” country.

There’s a similar issue over at Freedom Ship International, a Florida-based company that is hoping to raise the US$11 billion needed to build the world’s largest vessel.

Designed as a mobile floating platform stretching over 1,600 metres, Freedom Ship – which could set sail renamed as the Global Friend Ship – is designed to host an entire city of up to 100,000.

Just under half that number will reside permanently on the ship, which will make its way slowly around the world’s coastal regions over three years.

As it moves, a fleet of ferries and small aircraft (there’s an airport on the roof) will take residents to shore – as tourists or businesspeople – and bring tourists onboard to visit the 2.7-million-tonne vessel’s casinos, restaurants and businesses. It will have schools, a hospital and a security force.

“It’s the first ever floating city,” says Roger Gooch, director and vice-president of Freedom Ship International, “but it’s too large to go into a port so it will also stay around 15 miles [24 kilometres] offshore in international waters.”

Freedom Ship is designed to let people get away from the normal restrictions of global geography and governments, he says.

There’s a similar reason behind another offshore entity called Blueseed. A purpose-built floating platform registered in the Bahamas but moored in international waters 22 kilometres from the shores of San Francisco, Blueseed is aimed at international entrepreneurs who can’t enter the US (Silicon Valley, in particular) to start companies because of restrictive visa issues.

Offering its occupants – all with a US business or travel visa – daily 30-minute ferry rides to the mainland as well as helicopter trips, Blueseed will begin life next year on a refitted cruise ship, progressing to the custom-built Blueseed Two floating city soon after.

But life at sea isn’t just restricted to land-based humans. Olthuis has a vision of a Sea Tree, a multi-storey floating structure similar to an oil rig that could be placed in rivers, lakes and oceans near densely populated cities.

“Instead of creating green areas in the city, make them on the water,” he says. “When nature starts to colonise a Sea Tree then birds, animals and insects will use it, too.”

Olthuis already has a way to pay for it. “I could see oil companies donating Sea Trees to cities in return for drilling rights,” he says.

A Sea Tree in Victoria Harbour? That really would give Hong Kong a new look.

Meet the man who builds things on water, from slum schools to $14 million villas

Quartz, Siraj Datoo, Aug 2013

Dutch architect Koen Olthuis specializes in building things that float. His structures, he concedes, use a similar technology to oil rigs. Yet Olthuis’s focus is elsewhere—on combating rising sea levels, floods, and a growing world population. As he outlined in a TEDx Warwick talk last year, the work he’s doing is quite literally putting land where there wasn’t any before.

Olthuis is the founder of architectural firm Waterstudio.NL, and as a native Dutchman, he often cites his own country’s history as inspiration. “In Holland, we have always been fighting against the water… 50% is under sea level,” he said in his talk. Yet he finds this ongoing battle with water “strange”, arguing that it makes the country susceptible to danger. “What if something breaks?” he said in a phone call with Quartz. His solution: “Why don’t we just use the water?”

His projects include designing homes in Holland, schools in slum neighborhoods in Bangladesh, “amphibious houses” in Colombia, a star-shaped conference center, and a 32-island golf course (with, yes, underwater glass tunnels linking the islands) in the Maldives. He’s also looking to sign a contract to design villas in Florida.

How does it work?

There are three main elements here. The floating base:

[It] is the same technology as we use in Holland. It’s made up of concrete caisson, boxes, a shoebox of concrete. We fill them with styrofoam. So you get unsinkable floating foundations.And the bit on top?

The house itself is the same as a normal house, the same material. Then you want to figure out how to get water and electricity and remove sewage and use the same technology as cruise ships.

How it is anchored to the ground?

In Dubai, they just put sand into the water and made artificial islands. Once you put sand into the water, you can’t go back. We can go back after 150 years and there’s no damage to the habitat.

That’s impressive. So what do you do exactly?

[In the Maldives], these houses are connected to a floating boulevard… Those are connected to the sea bed with telescopic piles and as the boulevard rises up from sea level and the house rises up.And all that means that if there’s a rise in the sea level, due to a flood or tsunami, the island will just rise?

Yes.

“We don’t believe in donating money,” he tells me. “It didn’t work in the history [sic] and it won’t work in the future.” When you give money to charity, he argues, you rarely know what impact it has had.

His response to this is the City Apps Foundation. Instead of donating money for food and aid, companies provide financing for “apps”—interchangeable, prefabricated units such as classrooms, social housing, first-aid stations, or even parking lots. Like the apps on a smartphone, they’re designed to be easy to install and launch with the minimum of fuss. After an initial free trial, schools, governments and local municipalities can lease specific “apps” for a monthly fee. The fees yield a return for the investors, and when the apps are no longer needed they can simply be packed away and assembled in another city. The foundation has raised funding from a number of Dutch companies, and Olthuis and his company provide the technology.

The foundation’s first major project is a school in a slum in Dhaka. Olthuis says that slums have specific problems that appeal to him—in particular their instability. At any moment “the government can say that we’ll take the slums out or landlords might kick them out,” so slum-dwellers tend not to invest in their communities.

City Apps gives power to these neighborhoods, Olthuis argues, especially because they are often situated on the edge of water. In Dhaka, the school app will be a white container that stands out from the rest of the slum to create what Olthuis, perhaps inadvisedly, calls a “shock and awe effect”. The schools will contain iPads for use by the students, and women will use the space for evening classes. Within 12 weeks, the schools will have been built, transported to Dhaka, assembled and ready to use. If the community is forced to move, the school can move too with relative ease.

Olthuis says there are two ways that the City Apps foundation is a better system for investors:

It provides accountability. Cameras inside the containers will allow investors in the project to show off the fruits of their social spending to clients or shareholders in real time.

Although the initial school app will be free, slum-dwellers will have to pay to lease extra apps, such as what Olthuis calls “functions” for sanitation (this could be anything from a toilet to a fully-fledged bathroom) — or even just the ability to print. If the slum no longer wants a specific “function”, it can be easily taken away and used elsewhere. Investors get money if more “apps” are leased

“[It’s] stupid that each [sic] four years, we build complete neighborhoods and then they leave it there.” And it kind of is. The British government spent almost £2 billion ($3.1 billion) on venues alone for the Olympics and Paralympics village for London’s 2012 games. Instead, Olthuis suggests, Olympic cities should lease floating stadiums and property. This could be assembled in advance of the games and packed away afterwards, and would be far cheaper than creating new stadiums and neighborhoods every four years. While it would certainly remove some of the sparkle around the event, it would cut a good deal of waste. In Britain, talk of how the OIympic venues could be used after the games has already faded away.

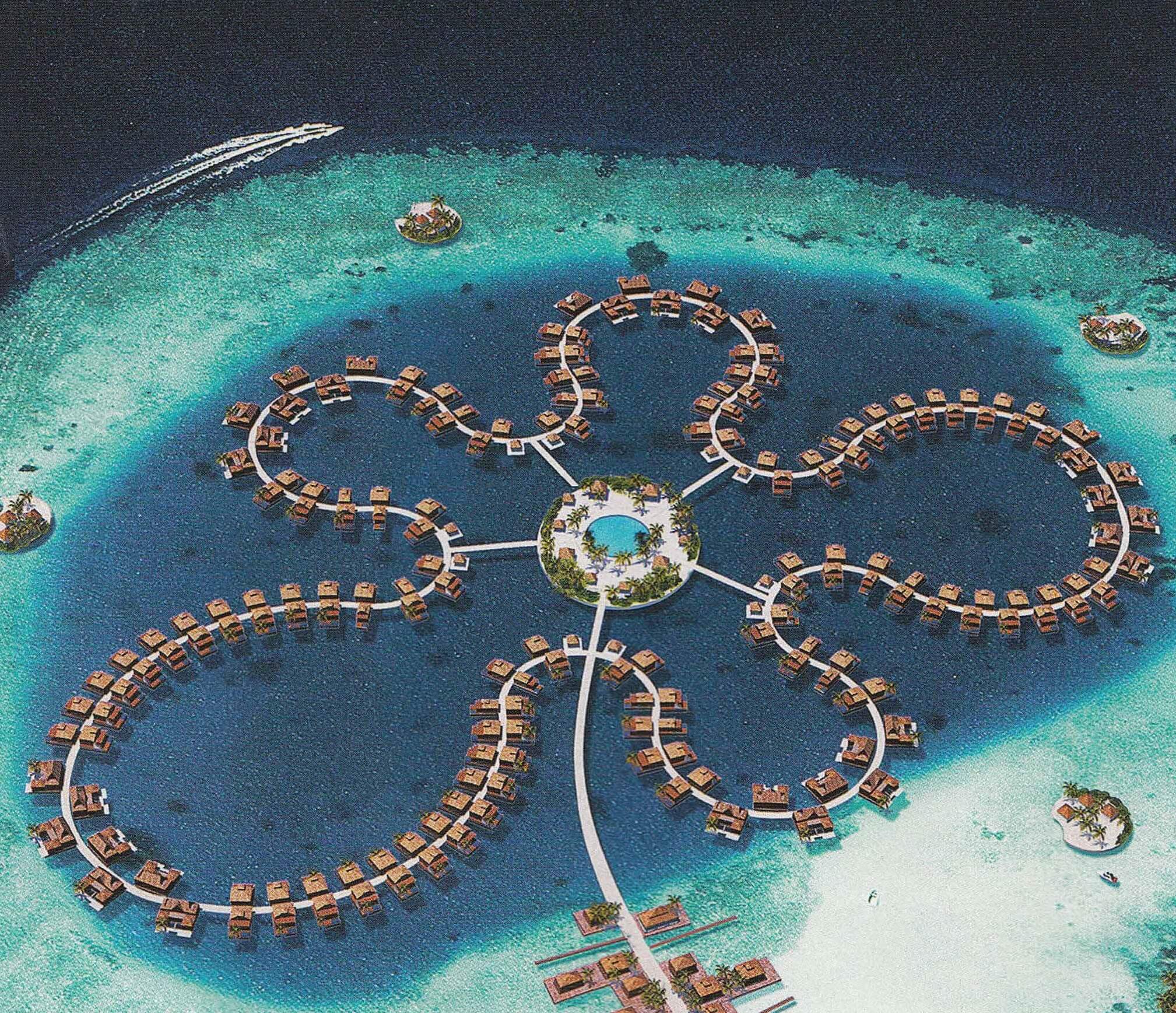

Work on the “ocean flower”, part of a project that will see 185 new floating villas, has already begun and the first villa will be inhabitable as soon as December this year. Americans, Chinese, Russians and even hotel operators have already forked out the $1 million cost per villa.

Olthuis has a contract with for 42 amillarah islands (private villas in the Maldivian language). These will be 2,500 sq. meters (26,910 sq. feet), and, at $12 million-$14 million, for the “stupidly rich”, Olthuis lets slip.

You can take a speedboat-taxi from the airport in 15 minutes or a three-person “U-boat” submarine will get you there in 40. (Russian president Vladimir Putin was seen modelling the five-person version.) Alternatively, spend three weeks learning how to maneuver a U-boat and a license is yours.

What if there was a hotel-cum-conference center in the middle of the ocean? Construction on this complex will begin towards the beginning of 2014 and with it come some interesting innovations. While a starfish has five “legs”, Olthuis’s company will build six. This means that if a section needs to be renovated, they could replace one leg with the spare (kept at the harbor) within three days instead of having to cordon off the area for months.

In his TEDx Warwick talk, Olthuis jokes that even if you’re on honeymoon in the Maldives, after a few days of glorious swimming, you kind of just want to play golf. And while the golf course might not be swarming with newly-weds, it might attract a new set of tourists from Russia and China.

Even if you’re not much of a golfer, it’s likely you’ll make a trip just to walk in the underground tunnels between the islands. And yes, the tunnel will be transparent.

Colombia has three big flood zones and every time there’s a flood, local municipalities have to pay a lot of money in compensation, according to Olthuis. To combat this, the local government has signed up Waterstudio.NL to build 1500 “amphibian” houses with a floating foundation.

So while the above photo depicts a floating house in a dry season, the house will simply rise in a wet season. While it’s a fairly simple concept, it has radical implications.

Olthuis’s biggest impact so far has been in Holland, where a number of water villas have already been completed. With over 50% of the country below sea level, this provided the perfect playground for his concepts to become a reality

City apps

The petropolis of tomorrow, Neeraj Bhatia & Mary Casper, 2013

In recent years, Brazil has discovered vast quantities of petroleum deep within its territorial waters, inciting the construction of a series of cities along its coast and in the ocean. We could term these developments as Petropolises, or cities formed from resource extraction. The Petropolis of Tomorrow is a design and research project, originally undertaken at Rice University that examines the relationship between resource extraction and urban development in order to extract new templates for sustainable urbanism. Organized into three sections: Archipelago Urbanism, Harvesting Urbanism, and Logistical Urbanism, which consist of theoretical, technical, and photo articles as well as design proposals, The Petropolis of Tomorrow elucidates not only a vision for water-based urbanism of the floating frontier city, it also speculates on new methodologies for integrating infrastructure, landscape, urbanism and architecture within the larger spheres of economics, politics, and culture that implicate these disciplines.

Articles by: Neeraj Bhatia, Luis Callejas, Mary Casper, Felipe Correa, Brian Davis, Farès el-Dahdah, Rania Ghosn, Carola Hein, Bárbara Loureiro, Clare Lyster, Geoff Manaugh, Alida C. Metcalf, Juliana Moura, Koen Olthuis, Albert Pope, Maya Przybylski, Rafico Ruiz, Mason White, Sarah Whiting

Photo Essays by: Garth Lenz, Peter Mettler + Eamon Mac Mahon, Alex Webb

Research/ Design Team: Alex Gregor, Joshua Herzstein, Libo Li, Joanna Luo, Bomin Park, Weijia Song, Peter Stone, Laura Williams, Alex Yuen

Co-published with Architecture at Rice, Vol. 47

Bouwen op water, waarom niet?

Mondiaal Nieuws, RENÉE DEKKER

Bouwen op water, waarom niet?

Steden worden wereldwijd steeds voller vanwege de trek naar de stad. Koen Olthuis, architect, had een eenvoudige maar revolutionaire ingeving om het gebrek aan ruimte aan te pakken: ‘Waarom niet bouwen op water?’ Speciale drijvende funderingen stelden Olthuis in staat om dit te realiseren. MO* sprak met de Nederlander over hoe bouwen op water ook kansarmen in het Zuiden ten goede kan komen.

Koen Olthuis, eigenaar van het architectenbureau Waterstudio, werd omwille van zijn FLOAT!-project door Time Magazine opgenomen in de lijst “Most influential people 2007”. Het Franse tijdschrift Terra Eco stelde in 2011 dat Olthuis één van de honderd “groene personen” is waarvan de wereld nog veel mag verwachten. Zijn passie voor drijvend bouwen leverde Olthuis ook de bijnaam “Floating Dutchman” op.

Steden zijn niet vol

Olthuis over zijn eigen idee: ‘Als architect kreeg ik regelmatig te horen dat de steden vol zijn. Daarom moet ik in steden zoals New York eerst op zoek gaan naar een pand dat gesloopt kan worden, pas dan kan de bouw van een nieuw project starten. Zo zijn we al snel drie jaar verder voordat een nieuw gebouw af is. Soms zijn de behoeftes van de stad dan al veranderd, met als gevolg dat gebouwen sneller hun houdbaarheidsdatum passeren en opnieuw gesloopt zullen worden.’ Voor dit probleem wilde Olthuis een oplossing zoeken.

De inspiratie hiervoor vond Olthuis niet ver van huis: in het dichtbevolkte Nederland is jaren aan landwinning gedaan om de bebouwbare grond uit te breiden. ‘Toch werkt dit systeem niet optimaal. Omdat een groot deel van Nederland onder de zeespiegel ligt, moet er dag in dag uit gepompt worden om het land droog te houden.’

Gewone huizen bouwen op water, het kan!

Zo kwam Olthuis op het idee om op water te bouwen. ‘Dit bestaat natuurlijk al in de vorm van woonboten. Maar dit voldoet niet aan de eisen van de meeste consumenten van vandaag. Daarom wilde ik gewone gebouwen en huizen kunnen bouwen op water.’ Hiervoor gebruikt Waterstudio een speciaal soort drijvende fundering, die zeer stabiel en veilig is. ‘Doordat negentig procent van alle grote steden op aarde in de buurt van water liggen, creëert dit heel veel nieuwe bouwruimte.’

‘We moeten ook af van het idee dat gebouwen statisch zijn.’ Olthuis verwijst naar de Olympische Spelen: ‘Daarvoor wordt er iedere vier jaar een volledige stad uit de grond gestampt, maar na afloop worden die gebouwen vaak nauwelijks meer gebruikt. Zou het niet beter zijn als we eenmalig drijvende stadions en andere gebouwen konden bouwen om die vervolgens iedere vier jaar over water te verplaatsen naar een andere stad?’

Steden als smart phones

Olthuis’ project City Apps speelt hierop in. Het project ziet steden als smart phones: ze zien er aan de buitenkant allemaal ongeveer hetzelfde uit, maar toch heeft iedereen er andere applicaties op staan. ‘Zo is het ook met steden: iedere stad heeft andere behoeftes. Door drijvend te bouwen, kan men de stad constant aanpassen aan de noden, simpelweg door gebouwen te verslepen naar een andere plaats binnen de stad of zelfs een andere stad.’ Drijvend bouwen is daarom ook duurzamer: gebouwen die anders gesloopt zouden worden, kunnen een tweede leven krijgen op een andere plaats.

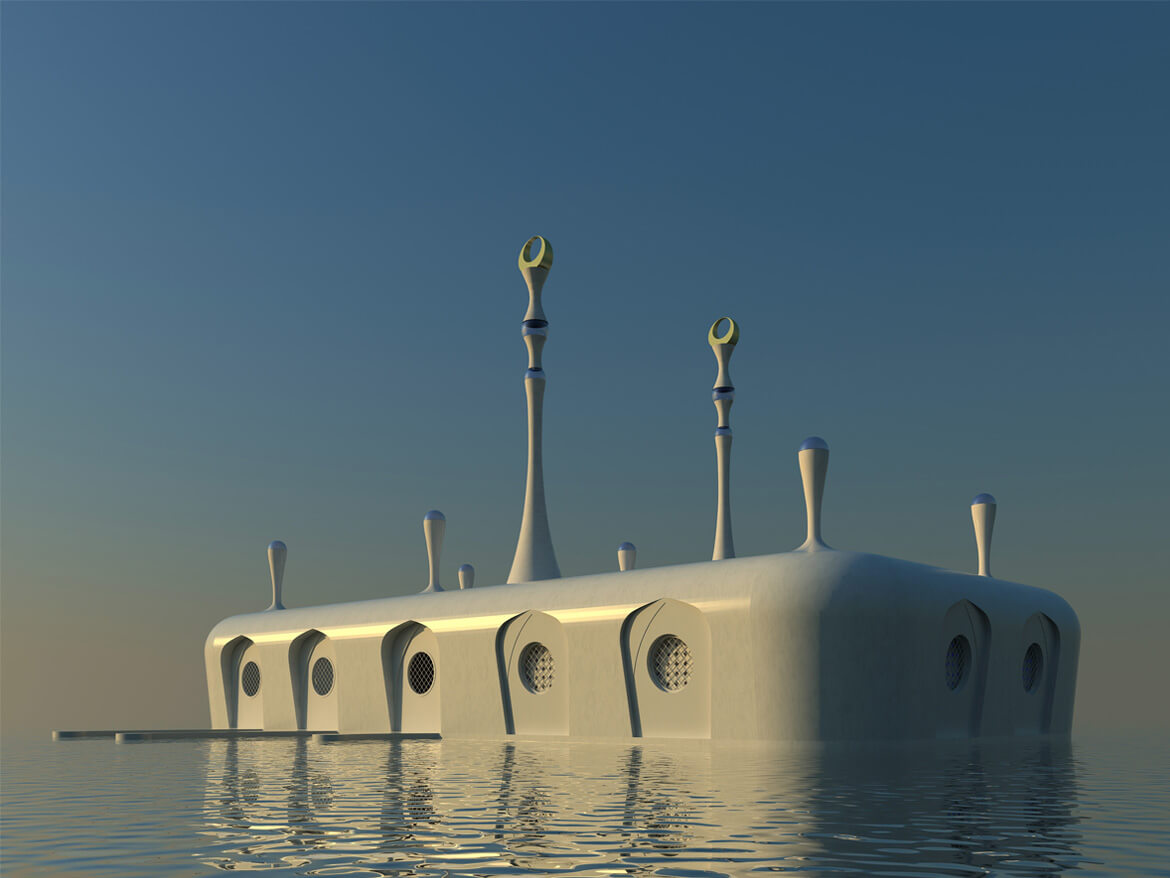

Bouwen op water is inmiddels geen toekomstmuziek meer: op dit moment lopen er drijvende bouwprojecten van Waterstudio in Miami, de Malediven en Saoedi-Arabië. Het gaat onder andere om moskeeën en luxehotels. ‘Maar mijn bedoeling met dit project was dat ook juist de armen in het Zuiden ervan zouden kunnen profiteren. Neem nu sloppenwijken, die liggen bijna altijd in gebieden nabij water, omdat niemand anders het aandurfde daar te bouwen.’

Sloppenwijken geen tijdelijk fenomeen

‘Velen gaan er van uit dat sloppenwijken tijdelijk zijn, maar dat is een misverstand. Veel sloppenwijken zijn niet erkend door de overheid, maar toch blijven ze bestaan en groeien ze zelfs. Steeds meer overheden zijn zich hiervan bewust. Ze zijn sneller geneigd om een sloppenwijk een reguliere status te verlenen wanneer er voorzieningen aanwezig zijn. Vaak ontbreken deze totaal, waardoor de wijken een onzekere status behouden’.

En juist in deze behoefte naar voorzieningen kan Olthuis’ City Apps-project voorzien: zo ontwikkelde hij drijvende sanitairblokken, zonnecollectoren, waterreinigingsinstallaties en wasruimtes, speciaal voor sloppenwijken. Op dit moment lopen er twee projecten in het Zuiden: een in de Thaise hoofdstad Bangkok en een in de Bengaalse hoofdstad Dhaka. Beide steden liggen aan het water en worden regelmatig getroffen door overstromingen.

Drijvend sanitair

Vaak is niet precies bekend waar de sloppenwijken liggen, omdat ze op geen enkele officiële kaart staan aangegeven. Olthuis wilde hierin verandering brengen: ‘Middels het wet slum-project brengen we in samenwerking met UNESCO de bestaande sloppenwijken in kaart. Daarna onderzoeken we lokaal wat er nog ontbreekt aan voorzieningen en indien mogelijk leveren we die.’ De City Apps Foundation die Olthuis oprichtte leverde in Bangkok al een sanitair blok, in Dhaka een telecommunicatie-eenheid.

Klimaatverandering zal harder toeslaan in het Zuiden, onder andere door extreem weer zoals stormen of overstromingen door overmatige regenval. Drijvende huizen zijn hier even goed of zelfs beter tegen bestand dan “gewone” huizen volgens Olthuis. Ook natuurrampen zoals aardbevingen en tsunami’s zouden drijvende huizen moeten kunnen doorstaan.

Strijd tegen klimaatverandering

‘Daarnaast bieden drijvende voorzieningen ook de mogelijkheid tot directe noodhulpverlening in geval van rampen: we kunnen bijvoorbeeld een drijvende vluchtruimte naar Bangladesh brengen als overstromingen dreigen of sanitaire voorzieningen brengen als een ramp al heeft plaatsgevonden.’ Ook voor landen die sterk getroffen zullen worden door de stijging van de zeespiegel, zoals de Malediven, kan drijvend bouwen een oplossing zijn.

Bouwen op water is nuttig in de strijd tegen klimaatverandering, want drijvend bouwen kan, net als op land bouwen duurzaam en klimaatneutraal. Zo heeft de drijvende moskee die Olthuis bouwde een airconditioningsysteem dat water benut om de binnentemperatuur te doen dalen. Drijvend bouwen is ook veel minder schadelijk voor de ecosystemen onder water dan bijvoorbeeld landwinning.