The skyscraper NATURE RESERVES: Architects hope to build £790,000 multi-storey habitats above and below water in cities

By Victoria Woollaston

Daily Mail

September.19.2014

With green spaces being replaced by building sites and large-scale developments around the world, architects are constantly looking for ways to replace them.

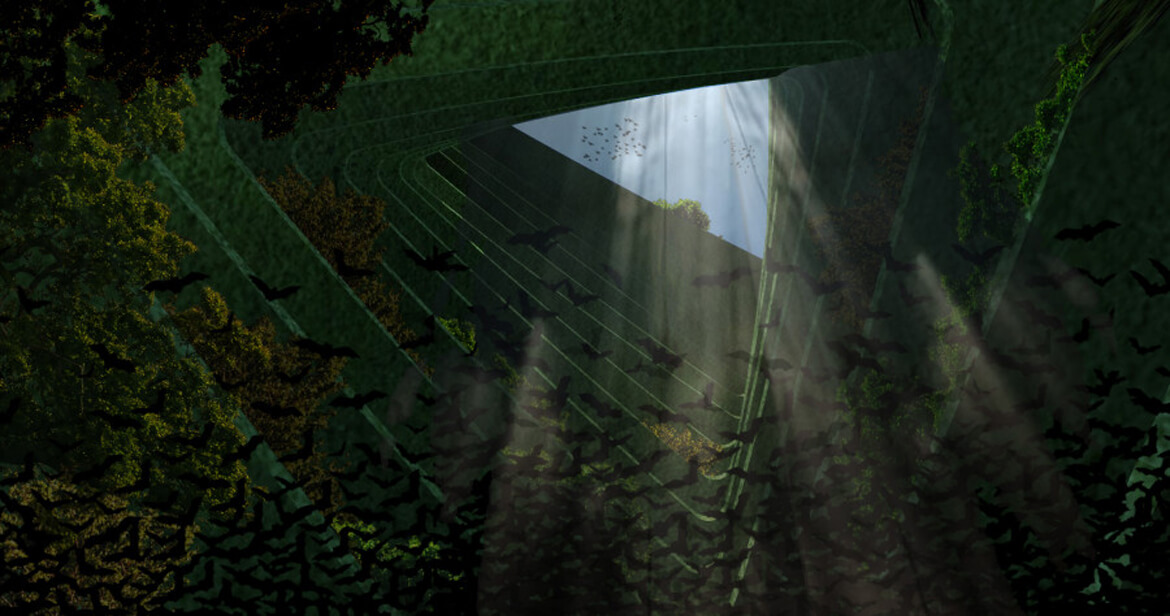

One such concept, devised by a team Dutch-based architects, uses towering structures built with layers of green space in which flora and fauna could live.

Called the Sea Tree, the structures would have space for birds and animals to live above ground, and would be bedded under the sea for fish and coral to inhabit.

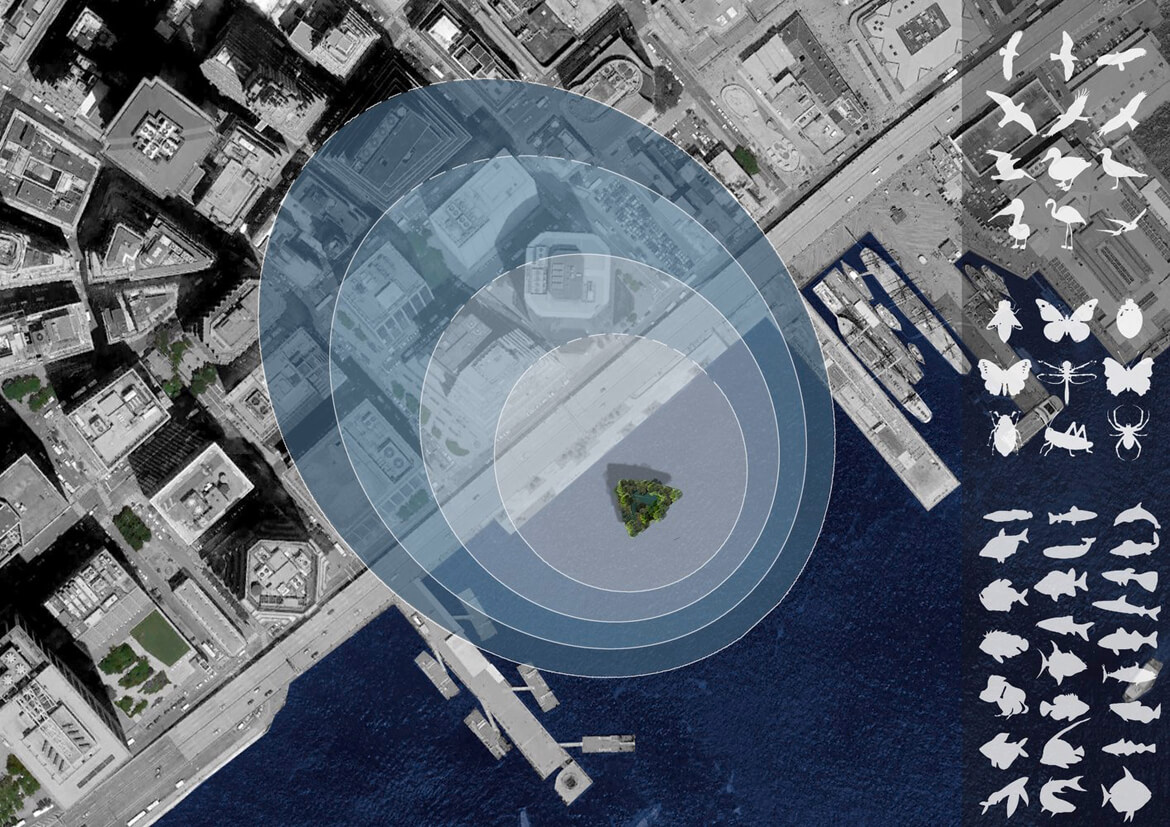

‘Urbanisation and climate change put a lot of pressure on available space for nature in city centres,’ explained Waterstudio.

‘New initiatives for adding extra park zones to a city are rare.

‘Yet these kind of additional habitats for birds, bees, bats and other small animals could bring a lot of positive green effects to the environment of a city.’

Waterstudio’s concept is called the Sea Tree and it was designed to add high density, green spots to towns and cities.

According to designs, it would be a floating structure built using layers where animals and birds can live.

The structures would not accessible by man, and would be built using offshore technology and resources, similar to how oil storage towers are built and powered out at sea.

The idea is that large oil companies would donate a Sea Tree, and the trees could be built on rivers, seas, lakes and harbours.

The height and depth of the Sea Tree could also be adjusted depending on where it was placed.

To hold it in place, Waterstudio claims Sea Trees would be moored to the sea bed with a cable system.

Under the water, the Sea Tree would provide a habitat for small water creatures or, if the climate allowed for it, artificial coral reefs.

As well as providing a home for nature, the green structures could help reduce CO2 emissions produced by cities and towns.

‘The beauty of the design is that it provides a solution, and at the same time does not cost expensive space on land.

‘While the effect of the species living in the Sea Tree will affect a zone of several miles around the moored location.

‘For as we know, this floating tower will be the first floating object 100 per cent built and designed for flora and fauna.’

The firm said inspiration came from a project in Holland where ecologists asked them to provide habitats for animals which couldn’t be disturbed by people.

The cost for the Sea Tree design is estimated at €1 million (£786,100), and this would depend on water depth, mooring facilities and transport from construction site to the chosen city.

Further cost differences would depend on the preferred flora and fauna.

Waterstudio said it is in the process of finalising the location of the trees, and discussing costs with oil companies. Once these are complete, they will start construction.

How Koen Olthuis is making floating cities a reality

By Sam Becker

Cheatsheet business

August.2014

According to the U.N., approximately 40% of the world’s population lives relatively close to a coastline. Even more than that live in close proximity to rivers and lakes. Together, rivers, lakes, and the sea all offer a wide variety of conveniences, resources, and a method of transportation, making human civilization inherently tied to the water itself. As water has universally been used as a means of exploration and transport for millennia, naturally it makes a fitting tool to use for tackling some of the world’s modern problems, including poverty and medical and education issues.

The question was how to best utilize it. Well, we may have our answer.

One man is revolutionizing the way the world sees cities by bringing a bold new idea to the table. Instead of viewing the idea of cities as static, brick-and-mortar establishments, Koen Olthuis instead likes to imagine them as flexible and malleable — able to adapt to the shifting needs of its citizens. Olthuis has an architectural firm based in the Netherlands called Waterstudio, which has been hard at work creating, among other things, floating houseboats, floating hotels, and even underwater structures. But Olthuis’ true target is the persistent and widespread poverty that sits adjacent to many of the world’s waterways, and use them as a means to deliver help in the form of hospitals and schools.

His idea is called Floating City Apps, which are constructed from recycled shipping containers and built on floating, barge-like structures, ensuring that they are easily moved from place to place, depending on where they are needed. The name comes from the idea of adjusting the apps on a mobile phone according to a user’s needs; City Apps would be able to reconfigure the layouts of slums in the same way.

So, how exactly would Olthuis’ idea work in the real world? As the Floating City Apps blog explains, “first a slum is mapped and local problems are related to water potential in the slum. The Floating City App with the most impact or effect is selected. With the help of our network, licenses and local manager or entrepreneur is selected. The Floating City App will be transported from The Netherlands to the slum.”

After the physical structure itself is shipped to its end destination, local licensees would then take over . “Locally the floating foundation will be built from collected used PET bottles supported by a steel frame. The City App is placed on the function a business model for payed use of the Floating City App is executed in order to get a ROI for the investors. In case of any change in situation the City App can be reused relocated or sent back to The Netherlands.”

In a nutshell, the Floating City App functions as a small business, which is built in the Netherlands and shipped to wherever it is needed. It is then licensed to a local entrepreneur until it is no longer deemed necessary or wanted.

The idea itself is a bit unorthodox, but it does set the wheels in motion for some interesting business models, and could be a very effective way to strategically build in areas of need. In fact, in a way, Floating City Apps open up a route for entrepreneurs to engage the free market in an entirely new way — by offering public services like sanitation or education to places that may be severely lacking.

Imagine a City App anchored dockside near an under-served community that offers Internet access to those who have never had it before? Or even a floating medical center after a natural disaster? The potential applications are numerous, and the idea lends a whole new way to how architects, planners, and engineers can use the topographies of certain cities.

With other factors like climate change leading to impending sea level rises, Floating City Apps may become less of an out-of-the-box idea and more of a necessity in the near future. The idea appears to have merit, and there’s really nothing standing in the way of its feasibility. There are many cities and areas across the world that could benefit from the use of floating service centers. Olthuis himself notes during his TED Talk, seen above, that cities are still built the way they were hundreds of years ago, and engineers need to find a way to take advantage of the water and the space that it provides.

“They’re flexible, they’re reusable, and can work as instant solutions,” Olthuis said of his Floating City Apps. “And they can be much more than only housing. All kinds of functions we can use (them for). Islands, floating beaches, cruise terminal, floating rotating tower, floating roads, agriculture, even a complete floating forest.”

“Almost anything you can think of can also be done on the water,” he adds.

If even a fraction of those ideas are able to be successfully pulled off in the real world, Olthuis’s idea could, in fact, be world-changing. For cities that are located next to large bodies of water and that are densely populated — think locations in Asia or Europe — entirely new neighborhoods could spring up to alleviate congestion and density.

Of all the potential applications, perhaps the most exciting concept is that of floating agriculture. If food production can be brought to dense inner cities bordering bodies of water, fresh and more affordable food would become available to those who desperately need it. Even in America, imagine the advantages a floating corn farm in an inner-city bay would bring to local residents. Granted, there are a lot — a whole lot — of factors to consider. But think of the transportation costs that could be cut out by having a food resource ten minutes away from grocery stores, rather than thousands of miles, in America’s heartland.

Olthuis’s idea certainly is bold, if not ingenious. The next step, of course, will be to see if investors jump on board and if the concept can be put to practical use. Even if Floating City Apps take a long time to gain momentum and take to the waterways of the world’s cities, it’s the kind of thinking being displayed by Olthuis that will truly help change the world for the better.

With the challenges the world’s population is set to face in the coming decades and centuries, we’ll need all the radical ideas we can muster.

Stjernearkitekter vil bygge flytende luksushotell i Tromsø

By Nordnytt

August.21.2014

Tromsø kommune har i dag signert en intensjonsavtale med selskapet Dutch Docklands om å bygge et flytende hotell utenfor byen.

Avtalen betyr at kommunen stiller seg positiv til at det femstjerners luksushotellet skal bygges i Tromsø.

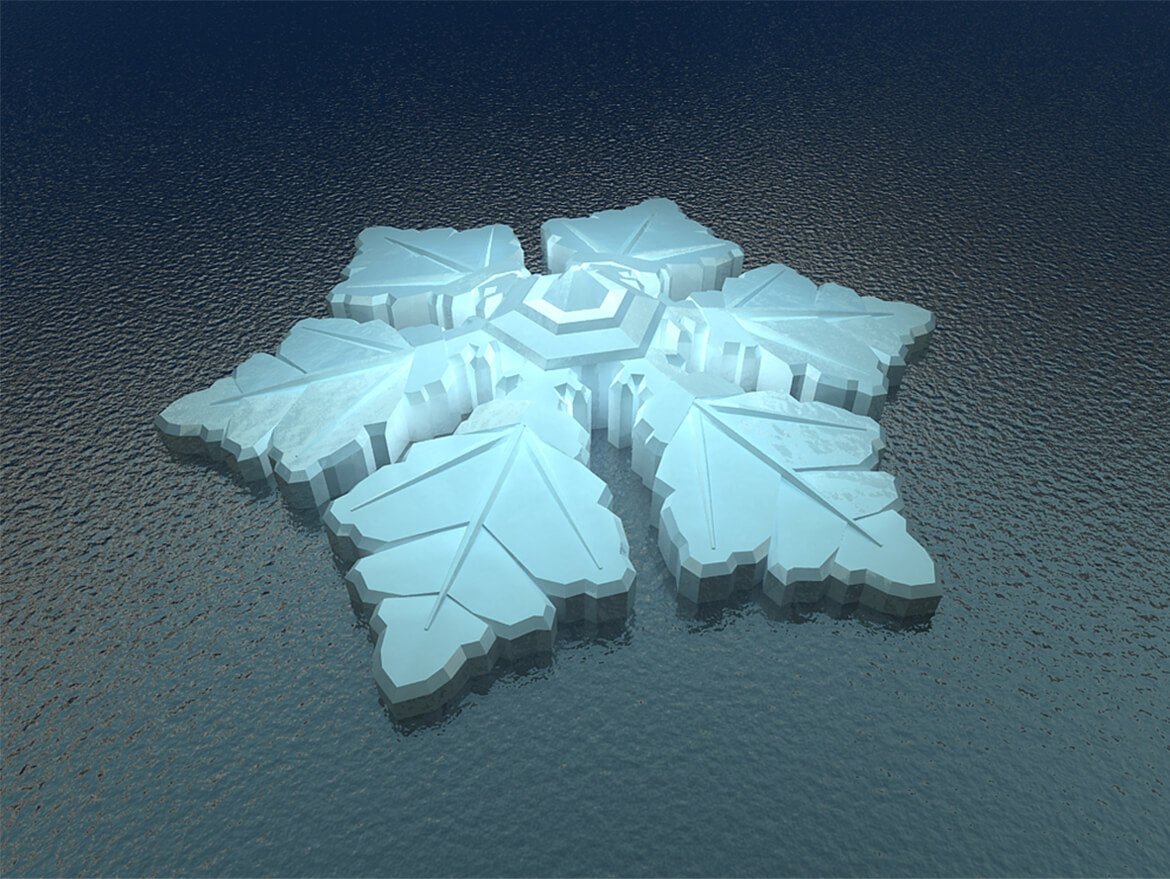

Det nederlandske selskapet Dutch Docklands har planer om å bruke 500 millioner kroner på luksushotellet, som skal utformes som en flytende iskrystall, og inneholde 86 rom.

– Vi planlegger å bygge det mest luksuriøse hotellet i den nordlige delen av verden. Det vil bli et unikt femstjerners hotell som vil gi gjestene en opplevelse med nordlyset, men også andre aspekter av Norge og av denne delen av verden, sier Paul van de Camp administrerende direktør i Dutch Docklands.

Selskapet er eksperter på flytende konstruksjoner, og har tidligere blant annet bygget luksushotell på Maldivene.

For pengesterke gjester

Han sier at Tromsø ble valgt på grunn av historien sin, men også på grunn av at byen allerede har utbygd infrastruktur når det kommer til turisme.

– Er det et marked for et slikt hotell?

– Det vil bli et lite hotell, men i den øvre enden av skalaen. Det betyr at romprisene vil bli høyere enn det som allerede finnes på markedet i Tromsø. Vi retter oss mot folk som er villig til å betale for et visst komfortnivå og for å få opplevelser i nordlige strøk. Det er et enormt globalt marked for dette, sier van de Camp.

Nå skal selskapet samarbeide med kommunen om å få på plass de nødvendige tillatelsen, og finne ut hvor det flytende hotellet skal ligge.

Hvor og hvordan det skal bygges er ennå ikke avklart.

– Vi ønsker vanligvis å få gjort mest mulig av dette lokalt. Vi vet at norske håndverkere er kjent for å holde en høy standard, akkurat som nederlandske. Det viktigste for oss er kvaliteten på arbeidet, og får vi dette til lokalt, så støtter vi det, sier van de Camp.

Kommunen positiv

– Vi har skrevet under på en avtale om at vi er positive til at dette hotellet kommer til Tromsø kommune for å etablere seg her. Vi kan bistå med kartmateriale, og når de har funnet fram til hvor de vil at hotellet skal ligge, så kan vi ha et oppstartsmøte, sier Britt Hege Alvarstein byråd for byutvikling i Tromsø kommune.

Hun sier at kommunen nå driver med en revidering av kommuneplanen og en kystsoneplan for Tromsø.

– Vi har ikke tatt høyde for at vi skal ha et flytende hotell i kommunen, så det må vi nå ta høyde for, sier Alvarstein.

Plan- og bygningsloven, reguleringsplaner og ikke minst skipsleden i Tromsø blir førende for hvor hotellet kan ligge, men det blir trolig i en av fjordene rundt byen.

Miljøprofil

– Selskapet har sagt at de ønsker at hotellet skal ligge rundt en times reise unna flyplassen, sier Alvarstein.

Hun peker på at selskapet bak hotellet har en miljøprofil og blant annet samarbeide med UNESCO for å ta vare på miljøet rundt og under der de bygger, så de lager minst mulig fotavtrykk i naturen.

– Det er spennende teknologi som tas i bruk, og ets pennende prosjekt på alle områder, sier Alvarstein.

– Er det ikke allerede nok hotellrom i Tromsø?

– Vi så både under sjakk-OL og Arctic Race at det ikke var rom å oppdrive, så kommunen har ennå behov for flere hotellrom. Men dette er jo et marked som kommer utenom det vanlige. Det vil være med på å forsterke det eksisterende tilbudet i byen, mener Alvarstein.

Dutch solution to Miami’s rising seas? Floating islands

By Jenny Staletovich

Miami Herald

August.23.2014

Maule Lake has been many things over the years: industrial rock pit, aquatic racetrack, American Riviera. Now it is being pitched as something else entirely: a glitzy solution to South Florida’s rising seas.

In the land of boom and bust where no real estate proposition seems too outlandish — Opa-locka’s Ali Baba Boulevard connects to Aladdin Street in one of the more kitschy bids to sell swampland — a Dutch team wants to build Amillarah Private Islands, 29 lavish floating homes and an “amenity island” on about 38 acres of lake in the old North Miami Beach quarry connected to the Intracoastal Waterway just north of Haulover Inlet.

The villa flotilla, its creators say, would be sustainable and completely off the grid, tricked out to survive hurricanes, storm surge and any other water hazard mother nature might throw its way. Chic 6,000-square-foot, concrete-and-glass villas would come with pools, boathouses or docks, desalinization systems, solar and hydrogen-powered generators and optional beaches on their own 10,000-square-foot concrete and Styrofoam islands.

Asking price? About $12.5 million each.

If this sounds like a joke, think again. This, as the Dutch say, ain’t no grap.

“We’re serious people,” said Frank Behrens, vice president of Dutch Docklands, which has partnered with Koen Olthuis, one of Holland’s pioneering aqua-tects.

Still, it’s hard not to be skeptical.

“It’s both fantastic and fantastical,” said North Miami Beach City Planner Carlos Rivero, before adding, diplomatically, “This is quite a departure.”

Behrens won’t say exactly how much the company has invested so far but suggested it is enough to take the plan seriously.

“Look who I’m sitting next to,” he said during an interview, pointing to Greenberg Traurig shareholder attorney Kerri Barsh and Carlos Gimenez, a vice president at Balsera Communications and son of the county’s mayor, both hired to help ensure the project’s success. “This isn’t like, ‘Oh, let’s buy a lake and do a project and make money.’ It’s ‘Let’s buy a lake and show people what we’re capable of.’ ”

Together Dutch Docklands and Olthius’ firm, Waterstudio.NL, have completed between 800 and 1,000 floating houses in Holland along with 50 other projects including — if there were any question about their design chops —a floating prison near Amsterdam. The team is also constructing the first phase of a 185-villa floating resort in the Maldives — Behrens said 90 have already sold. Olthius also designed a snowflake-shaped floating hotel in Norway, floating mosques in the United Arab Emirates and even a floating greenhouse out of storage containers usually used by oil companies.

The team believes that by building an extreme example of a floating house in Miami, with every bell and whistle imaginable, it can open up a new American market to a way of building that has addressed rising waters in the Netherlands for a century.

“We chose Miami because we know this city is one of the most affected cities by sea-level rise,” Olthuis said by phone from Holland. “Once it’s done, you’ll see it’s a beautiful archipelago effect in the lake.”

So can you get a mortgage? Buy windstorm insurance? Declare a homestead exemption?

Yes, yes and yes, Barsh said. Practically speaking, the barge-like structures are considered houses, not boats, she said. A 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision on a Riviera Beach houseboat that Barsh helped argue cleared the way by declaring floating homes real estate. After the victory, Barsh started talking to Behrens — they met through the Dutch Chamber of Commerce he founded in Miami in 2011 — about Dutch-style floating homes in the United States.

“Before, there was a lack of clarity,” Barsh said. The court decision “opened up an opportunity for this development to go forward.”

Barsh, who also represents rock-mining interests, says such projects could potentially provide a valuable way to reuse rock pits scattered throughout South Florida.

But what would it mean for the manatees that lumber through the saltwater lake, which is designated critical habitat?

Protections would remain in place, the team said. And the islands, with specially contoured undersides, could provide a habitat for sea life, Behrens said.

Still, making the project fit local laws could be tricky. In a preliminary review by the North Miami Beach city staff, Rivero raised questions as mundane as the need for parking. The city’s civil engineer wondered about stormwater runoff, among other things. And police say they would need a boat from the developer to patrol the islands. There’s one other thing: North Miami Beach’s rules for such developments so far apply only to land.

Luis Espinoza, spokesman for the county’s Division of Environmental Resources Management, said county officials would need to evaluate the islands for environmental impacts. And there’s the matter of taxes.

“If it’s a permanent-type fixture, then it will be assessed as property,” property appraiser spokesman Robert Rodriguez said.

Over the next 100 years, scientists predict climate change will alter water on a global scale. Seas will swell and coasts will shrink. Weather will become more extreme, with stronger hurricanes, harder rains and higher floods. Even routine tides will rise. And almost nowhere else will those effects likely be more dire than in South Florida, where beachfront highrises and marshy suburbs sit on soggy land kept dry by a complicated network of canals, culverts, pumps and other controls.

So solving the problems of coastal living in the 21st century could be lucrative.

“Here in Miami, it’s an artificial landscape, manipulated by mankind at a very high cost,” said Dale Morris, an economist with the Dutch Embassy in Washington, D.C., who is not connected to the Amillarah project. “So to think it can be maintained at no cost is nuts. I’m an economist. Nothing is free in this world.”

The floating islands, he pointed out, do nothing to solve larger climate problems for cities in South Florida, where flooding now occurs with normal high tides in Miami Beach.

Florida, like Holland, will have to tackle gradual sea rise in addition to event-related flooding like hurricane storm surges, Dutch landscape architect Steven Slabbers said at a recent workshop on resilient design in Miami.

“It’s an inexorable, decade-by-decade phenomenon,” he said.

Considering other Dutch designs — protective dunes tunneled out to hold parking, parks that become ponds and highways that float — a rock-pit-turned-floating-housing by using drilling rig technology might not seem so farfetched.

In recent months, the last new project on Maule Lake, Marina Palms, has shown that demand for lakefront property with Intracoastal access is high. Condos in the first of two buildings, which got the glam treatment this year on Bravo’s Million Dollar Listing Miami, sold out. But Maule Lake has not always been a twinkling star in the real estate firmament. It began life as a rock pit, when E.P. Maule moved from Palm Beach in 1913. Maule Industries would become the state’s largest cement manufacturing plant before falling into bankruptcy in the 1970s after it was purchased by Joe Ferre, whose son, former Miami Mayor Maurice Ferre, managed the company.

“That area was rich in rock pits, quarries and concrete manufacturing,” explained historian Paul George, who said the rock pits pocked the largely industrial area well into the 1960s.

The porous limestone mines fill with water from the area’s high water table. The new lakes provided even more waterfront property to an area already rich with water views, creating a developer’s dream — and possibly an environmentalist’s nightmare.

In addition to worries about marine life, building on the lake may raise concerns about water quality and potential effects on the nearby Biscayne Bay aquatic preserve and the Oleta River, another protected ecosystem. There might also be a question of encroaching on some of the area’s rare open space.

“We have a history in South Florida of viewing open spaces as a pallet for more product to be built on,” said Richard Grosso, a Nova Southeastern University law professor and director of the Environmental and Land Use Law Clinic. “Florida’s always been a place where we’ve suspended the laws of nature and physics and people haven’t always taken into account that there’s a finite amount of space.”

Gimenez, the public relations executive who is also a land use attorney, said the Dutch team has already met with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers about concerns. The team also plans to meet with neighbors. And while nothing has officially been submitted, he said no one has raised objections. The 7- to 13-foot-deep lake, he pointed out, is too deep to harbor much marine life or sea grass.

Gimenez also said floating islands are better than the alternative: filling the lake and building highrises. Once mined, rock pits are sometimes refilled with construction and demolition debris. Developers in Hallandale Beach, for example, are filling a 45-acre lake with debris to build an office park. Rivero, the planner, said a North Miami Beach ordinance prohibits the lake from being filled, although property trustee Raymond Gaylord Williams, who had the property listed with a local Realtor for $19.5 million, could challenge that.

But getting a variance from a county ordinance regulating waterways could be a feat, since so few are granted, said land use and environmental attorney Howard Nelson.

“Let’s face it, [what developer] wouldn’t rather replace a houseboat with a houseboat office,” he said. “All of a sudden you don’t have the bay anymore. You just have dock space after dock space after dock space with offices.”

Behrens, a former banker who grew up in Aruba and was CEO of a Miami-based Dutch distillery, said the team has been meeting with various regulatory agencies to size up the obstacles since 2013 and will resolve issues as they come up. They hope to have permits completed within the next year and a half, he said.

“It’s a step-by-step approach,” he said. “But we’re Dutch. …We know how to stay and how to make success.”

Could floating shipping containers help sort out the world’s slums?

By Barbara Speed

Written by Citymetric

August.14.2014

“What if a city was as flexible as a shuffle puzzle?” Koen Olthuis asked in his 2012 TEDx talk. He was referring to those games in which you move squares around until you make a picture. At the time, his audience probably didn’t realise he was serious.

But using moveable little boxes to meet a city’s needs were exactly what Olthuis was proposing. His talk was on the subject of the “Floating City Apps” developed by his architectural firm, the Netherlands-based Waterstudio. (You may remember them from their plans for a floating golf course in the Maldives. Or maybe you saw their designs for a snowflake-shaped hotel off the coast of Norway.)

These mobile buildings would float on bodies of water at the edges of cities. They could also be moved around according to a city’s needs, and could fulfil a range of different functions. Some would be educational, with internet access and computers; others could act as bakeries, housing, healthcare centres, or floating mats of solar panels.

In June, the first piece of Olthuis’ shuffle puzzle was completed: an educational suite which will double up as an internet cafe in the evenings, all powered by solar panels on its roof. It’s been built inside a shipping container, to makes it easy to transport; a base constructed from thousands of plastic bottles collected by slum residents will be added once it reaches its destination.

It’s due to be shipped out to a slum in Manila in the autumn. Here’s the architect’s mock-up of the city app in situ.

Olthuis’ interest in water-based construction was inspired partly by his home country: around half the Netherlands lies below sea level, and massive amounts of water are pumped away daily to keep the country high and dry. But it’s not the low countries that could benefit most from this kind of architecture: it’s the rapidly growing and slum-packed cities of the developing world, and wet slums – those edging onto bodies of water, and so at risk of rising sea levels – were forefront in Olthuis’ mind when he came up with the idea:

“They’re some of the hardest areas to help, because they’re so close to the water,” he says. “People are unwilling to invest in development that could flood, or just wash away.” His hope is that these City Apps could help change that: the units they would rise with sea levels if an area floods, and could be moved elsewhere if necessary. This first app was funded by the prize money from the 2012 Architecture and Sea Level Rise Award, the studio and other sponsors; in future, the studio is hoping to build them then lease them out to NGOs and development agencies for a low monthly cost.

There’s a case for helping the world’s 1.1bn slum dwellers to more permanent settlements, rather than just improving the slums, of course. But in Olthuis’ view, “slums aren’t going to go away, so the only thing we can do is upgrade their prosperity”. There are a few creases to iron out first, though – at the moment, the studio may have to pay tax on transporting the Manila app, and are meeting with embassies to try and avoid this “real waste of money”.

While the city app will be run by a local organisation once in Manila, Olthuis is keen to stay involved. “The most important thing is that we can measure the app’s effects, and check how it’s working.” He wants to build hundreds, even thousands, more apps for different purposes around the world: 90 per cent of the world’s largest cities border a body of water, whether it be river, lake, or sea, so the project’s applications could stretch far beyond wet slums. Because of their floating foundations, the apps are relatively stable, though they may not work so well in waters prone to violent waves.

For Olthuis, floating architecture offers a way to use the dead space off the coasts of cities. It also offers flexibility, as units can be moved to a different location, or even another city, as the needs of the surrounding area change – just as you can change the apps on your phone.

Northern Lights watch from the floating snowflake hotel

Water Architect Koen Olthuis on How to Embrace Rising Sea Levels

Inhabitat, Bridgette Meinhold, July 2014

Sea levels are rising, floods are prevalent, and cities are at greater risk than ever due to climate change. Now that we’ve accepted these facts, it’s time to design and build more resilient structures. Koen Olthuis, one of the most forward-thinking and innovative architects out there, has a solution for rising sea levels. His solution: Embrace the water by incorporating it into our cities; creating resilient buildings and infrastructure that can handle extreme flooding, heavy rains, and higher water. Olthuis and his team at Waterstudio.nl have been showing coastal communities the benefits of building on the water. With countries like the Maldives and Kiribati having to build oceanside or move in order to escape rising sea levels, New York learning to battle storm surges, and Jakarta dealing with massive flooding, embracing water may be our only option for survival. We chatted with Olthuis about how coastal cities can become more resilient in the face of change—read on for our interview!

Sea levels are rising, floods are prevalent, and cities are at greater risk than ever due to climate change. Now that we’ve accepted these facts, it’s time to design and build more resilient structures. Koen Olthuis, one of the most forward-thinking and innovative architects out there, has a solution for rising sea levels. His solution: Embrace the water by incorporating it into our cities; creating resilient buildings and infrastructure that can handle extreme flooding, heavy rains, and higher water. Olthuis and his team at Waterstudio.nl have been showing coastal communities the benefits of building on the water. With countries like the Maldives and Kiribati having to build oceanside or move in order to escape rising sea levels, New York learning to battle storm surges, and Jakarta dealing with massive flooding, embracing water may be our only option for survival. We chatted with Olthuis about how coastal cities can become more resilient in the face of change—read on for our interview!

Despite his busy travel schedule, Olthuis had a chance to answer our questions with a great amount of detail and thought. Not only is Olthuis a leader in designing floating architecture, he’s the most-interviewed architect on Inhabitat. We think very highly of his work and ideas, and we think you’ll agree after reading through his thoughtful answers about the pressing issue of climate change. Don’t worry, it’s not all gloom and doom though—Olthuis proposes a future full of hope and promise!

Inhabitat: What does climate change mean for cities on the coast, and how serious is a sea level rise of 1 meter?

Koen: I think that climate change is a serious problem for these cities because most of them have been built upon the wrong parameters. For centuries, sea levels and climate have been relatively stable, which has brought us urban plans and built environments that are too static—like a one-trick pony for one certain set of conditions. With the arrival of uncertainty in , we have to rethink our coastal cities.

The threat that climate change brings is not just the physical threat of floods and drowning, but also the financial impact of destroyed property and businesses. Through the last century, waterfront development has increased in value as well as assets. Flood threats will put pressure on available dry space and reset the parameters for which parts of a city are desirable, and which are dangerous.

The effect of a one-meter sea level rise (without any adjustment to coastal cities as they stand today) would completely reset maps and financial stability in many of the world’s biggest waterfronts. New York, Miami, and Guangzhou would lose an important part of their real estate to the water. Countries like Bangladesh and the Philippines would have to give up lots of land. In the Netherlands, many of the water defense systems that protect the country under sea level will no longer be safe.

The question of how serious a one-meter sea level rise would be cannot be answered without placing this question in a certain timeframe. Although cities may appear static, they’re in constant change. The lifespan of urban components like infrastructure, normal buildings, and water defense measurements isn’t more than 50-100 years. This means that if the change occurs within the next 50-100 years, cities have time to grow into components designed upon the new parameters. If the rise occurs faster, cities won’t have time to adapt naturally and problems will occur. The problem is that because sea level rise is quite slow, governments find it hard to deal with a long timeframe when short-term strategies will lead to immediate benefits.

Inhabitat: What do coastal cities need to be thinking about and planning for in order to prepare for the inundation of water?

Koen: First, they have to design plans with flexibility—not solely for today’s conditions. Second, they might be better off embracing the water instead of fighting it, seeing urban water as a chance to upgrade our cities rather than a side effect.

I think that a resilient city isn’t one that prepares for the water to come, but one that allows it to expand. By letting in water and making it part of the city, rising levels or storm conditions will only mean working with a bit more water instead of the big shock that comes when conditions go from dry to flooded.

Regarding planning, coastal cities should focus on which areas should be kept absolutely dry, which can be changed from dry to wet, and which existing waters can be used for expansion. The future of resilient coastal cities is on the water, and metropolises like London, Miami, Tokyo, and Jakarta will expand their territory by 5 to 10 percent on urban waters in the next 25 years.

Inhabitat: Can you give us examples of any cities making promising strides to become more resilient?

Koen: Many are slowly taking defensive measures to become more resilient, but there is one that seems to use a highly innovative path: Jakarta. This capital of 10 million is suffering not only from climate change, but also from urbanization. The soil is sinking at a speed of 15 centimeters per year, which raises flood risks and effects, and it’s getting polluted with saltwater, which has a huge effect on fresh water reserves. Instead of building only higher water defense systems like dikes, which wouldn’t solve the saltwater problem, they’ve chosen to embrace more innovative solutions provided by Dutch engineers and urban planners. The solution focuses on closing Jakarta bay with a dike, turning it into one big 100 km2 wet polder; a size needed to provide enough storage area for extreme weather conditions.

On this dam, a city of a million people will be built facing the old waterfront of Jakarta on one side and the ocean on the other. For architects focusing on floating architecture, this kind of artificial large-scale wet polder provides a big opportunity: in order to keep the storage as big as 100 km2 you cannot build in the water, but floating structures have no effect on storage capacity. Jakarta can become one of the most resilient coastal cities of Asia and still make money from these measures—fighting water with water by adding the storage polder.

Inhabitat: If you were put in charge of making, say New York City, resilient to flooding and climate change, what strategies would you implement?

Koen: New York is one of the most iconic cities in the world, and Manhattan is the benchmark for high-density urban developments, but this city has also evolved to accommodate the surge for space. The enormous land expansion over the river beginning in the 17th century provided the city with new space. The elevator facilitated building into the air, and the metro system took advantage of space beneath the city. Without any of these innovations, Manhattan would look completely different. The lesson here is that standing still doesn’t always benefit cities, and innovations (daunting though they may appear) can bring new prosperity.

The biggest problem that New York will have to face isn’t a steady one-meter sea level rise—because that can be overcome with a meter-high levee—but the effects of extreme weather. Storm conditions like Hurricane Sandy will raise water a few meters and yield heavy rainfall that cannot be transported to the river, since the river itself will rise to record levels. To keep the subway system dry in normal conditions, huge amounts of water have to be pumped out; any additional water could make the system flood.

New Yorkers haven’t embraced the waterfront as much other coastal cities. The view inside is more important than outside and the most valuable real estate can be found around Central Park. [There are] no nice boulevards like in the south of France; nice beaches or green habitats can be found at their manmade border between land and water.

Having said this, I would bring the strategy of fighting water with water to New York and start wetting up the city. If we raise the level of the water ourselves by a few meters, it won’t be any problem when nature does it. To raise the level of the river and still use it as such is impossible, but there’s another Dutch solution that could work. In Holland, existing polders are surrounded by artificial canals. The water in these canals is a few meters higher than the polder waters. They aren’t dug into the landscape, but put on top of the landscape with a dike on both sides to keep the water in. Water from the polder is pumped into the canal and then transported to the rivers or the sea. The canals can be artificially controlled, providing a kind of buffer, and can also be used for transport, and waterside houses. I’d like to create a necklace of small, connected artificial lakes around Manhattan; a system much like an extra canal with a higher water level than the surrounding rivers. This canal would be divided into sections that could be closed separately.

This new zone will take the place of the existing harbor quay—the river width wouldn’t be affected, but the result would be like a set of airbags around the city. In case of high tide, these cells would serve as storage polders that could release water when the storm had passed. These cells would change the edge of Manhattan: the water cells would look like small lakes, and new settlements could be built on the levees dividing them from the river. These lakes would all be connected, and they’d only be closed off from each other during storm conditions, like compartments in large cruise ships.

The artificial lakes would fill the space now used by the river docks, and have a flexible water level that would provide an enormous storage zone, providing safety encroaching seawater. As I imagine, there would be as many as 40-50 of these lakes, each as long as 4-6 blocks. Lakes for leisure, for green floating communities, lakes with harbors—the greener the better.

Inhabitat: With countries like the Maldives and Kiribati losing their land to rising sea levels, how do they respond and provide for their citizens? Buy property elsewhere or construct floating cities? Are there estimates on how much it would cost to construct floating countries?

Koen: The Maldives and Kiribati are both series of small islands in the middle of the ocean, which will be highly affected by any sea level rise. Without enough dry land available, these countries have to make the choice to become climate refugees or adopt floating technologies and become climate innovators.

In the Maldives, Waterstudio has designed floating island resorts and a golf course for developer Dutch Docklands. They are building a joint venture with the government of the Maldives, both as a tool to increase new possibilities for tourism, and to reinforce society with long-term floating developments. Floating islands with high-density affordable housing could be added to the existing islands to provide space and safety. Floating developments are scar-less and mustn’t have any impact on marine environment during or after their lifespan.

This could lead to floating countries, keeping in mind that the Maldives has 300,000 inhabitants. The cost of these floating islands is comparable with dredging islands, only that dredging destroys sea life and coral reefs. If I must make a reasonable guess I would say around $25,000 per person, so for a city of 20,000 people it would cost 500 million dollars. This might sound like a lot, but it’s quite reasonable compared to evacuating a nation.

Inhabitat: How has your work changed over the years in response to the pressing needs of climate change?

Koen: The possibility of improving coastal cities worldwide with the implementation of floating urban components is just so challenging. It feels like we have only just discovered a small part of the potential that water could bring in making cities more resilient, safe, and flexible. I believe that projects like these will set new benchmarks for cities that would otherwise be in trouble because of climate change.

Our research seeks to change perception and dogmatic rules that traditional planners from the static era have put on us. I think that just in the last two years, iconic designs like the floating cruise terminal have developed an extra dimension—they’re part of a bigger vision that looks beyond iconic architecture to the economical impact it could bring.

My work has gone from designing for rich individuals to designing for the poor. We now design strategies for cities that have to adjust their planning approach because of shifting conditions due to climate change. The focus on slums has opened a whole new window of opportunity and has brought me in contact with many people who believe architects must use their influence and creativity to make a change for millions instead of only the happy few.

Inhabitat: Tell us briefly about your latest project, City Apps, and how it can help cities deal with climate change.

Koen: Miami and New York are the cities most threatened by sea level rise in terms of exposed real estate, but the populations most threatened by sea level rise would be in Mumbai, Dhaka, and Calcutta. In these cities, millions live in dense slums close to water. In fact, one billion people worldwide are living in slums, and half of them can be classified as wet slums because of their relation to the water. People living in these areas are terribly vulnerable to flood danger. Efforts to help these cities should not focus on protecting the built environment, but on protecting essential functions during and immediately after floods. Slums can be helped by upgrading programs to improve life conditions for 100 million people before 2020, as stated in the 2003 UN habitat millennium goal.

Programs in wet slums are not generally upgraded, because investing in them is a risky business, as floods could potentially destroy any functions built in areas close to the water. We want to use our technical knowledge to provide floating functions on water for these wet slums.

Just as you can download apps on your smartphone according to your changing needs, you can adjust functionality in a slum by adding functions with City Apps. These are floating developments based on standard sea-freight containers, and because of their flexibility and small size, they are suitable for installing and upgrading sanitation, housing, and communication.

Inhabitat: What advances in technology, design, or materials have helped push your architecture forward?

Koen: In Holland, we have always been close to maritime technology. It is very exciting to take these technologies that are meant for things like offshore oil industries and use them to create a floating habitat for animals, birds and underwater creatures like the Sea Tree does.

I think the Internet and 3D visualization tools have really pushed my architecture forward because in an industry as young as floating architecture, it is only the power of visualization that can show the impact of floating developments for the city of tomorrow. The fact that we can spread our ideas around the world and get feedback, response, and help because of the digital revolution is unbelievable. If I would have started twenty years ago I probably wouldn’t have reached more than half of Holland, and Holland isn’t that big.

My designs are what we call “readable architecture”—product-like solutions that ask for simple and clear details. Not every material is suitable for that, and over the last three years we discovered sustainable composites that suit the architectural expression I want, and are ideal for projects in salty environments that require low maintenance.

But the most important advantage in technology is logistics. The fact that we now can produce our floating houses and developments in different countries and assemble them on the water without affecting the environment makes it possible for us to rethink economical models for large-scale production.

Inhabitat: What are you most excited about right now in this field?

Koen: I am most excited about how global mobile assets will enable cities in developing countries to leapfrog to higher prosperity. These assets are large-scale floating developments that are being invested in by very rich countries like Qatar, Saudi Arabia, or Norway. These countries have so much money to invest that they cannot spend it all in their own country. Instead of investing only in wealthy world capitals, they’ll invest in flexible real estate, which can be leased to coastal cities.

It’ll start with functions like floating hotels and stadiums for cities that want to organize the Olympic Games but who cannot afford the investment. But it will rapidly evolve into an industry where cities that have been hit by climate change-related disasters can lease an entire set of functions like energy plants, hospitals, schools, and sanitation. Just like we do with our Floating City Apps for wet slums, there will be large-scale solutions to instantly upgrade cities and help communities recover. I see floating harbors and even small floating airports that’ll provide instant infrastructure to cities recovering from natural disasters.

The enormous financial capacity of these countries enables them to build global mobile assets up front on stock. So, imagine a safe floating location somewhere in Asia composed of completely functional urban components ready to be towed to any disaster area that appears. All the technology and money is already available—it’s only a matter of changing perception before floating developments are an essential part of the climate change reality that’s waiting for us. I say that not as a negative sentiment, because I believe that change will lead to innovation that will bring prosperity. The future is wet, the future is good!