Interview of the The New York Times with Koen Olthuis

CHRISTOPHER F. SCHUETZE NOV. 28, 2016

A Dutch Architect Offshores the Future of Housing

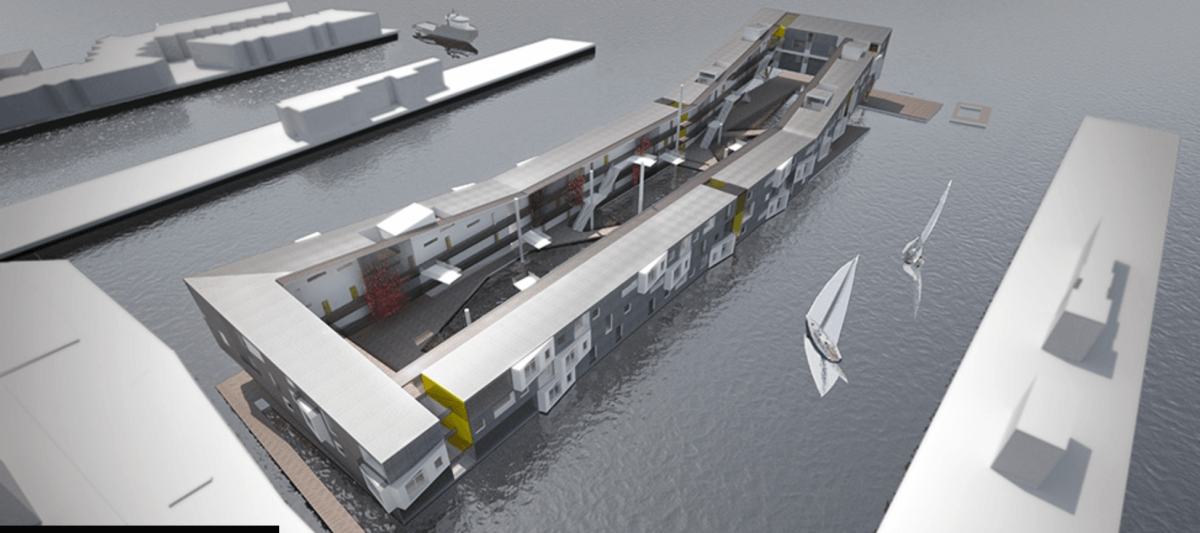

Floating houses in Amsterdam designed by Koen Olthuis. Mr. Olthuis’s architectural firm, Waterstudio, which he founded in 2003, has completed more than 200 floating homes and offices. CreditFriso Spoelstra/Waterstudio.nl

RIJSWIJK, The Netherlands — Early next year when a converted cargo container on a floating foundation of plastic bottles opens on the flood-prone shores of Korail Bosti, Bangladesh’s largest slum, few of its users are likely to celebrate the 320-square-foot space as a revolution. Yet, according to Koen Olthuis, the lead architect on the project, it is part of the greatest transformation in urbanism since Elisha Otis built the safety brake that gave rise to the modern elevator, skyscrapers and ultimately urban density.

“It will change the DNA of cities,” Mr. Olthuis said of the technology at the heart of his designs in an interview in his studio, a converted supermarket in this suburb of The Hague that also serves as his business headquarters.

In an era when the needs of growing urban centers are changing rapidly and rising sea levels threaten waterside construction, Mr. Olthuis has been busy working on a solution: the floating building.

Mr. Olthuis founded Waterstudio — which he describes as the first modern architecture firm to exclusively build floating houses — in 2003. More than a decade on, he and his team consider themselves pioneers in a growing movement. The firm has completed more than 200 floating homes and offices, many of them in the Netherlands, where several floating neighborhoods have sprung up in the last decade.

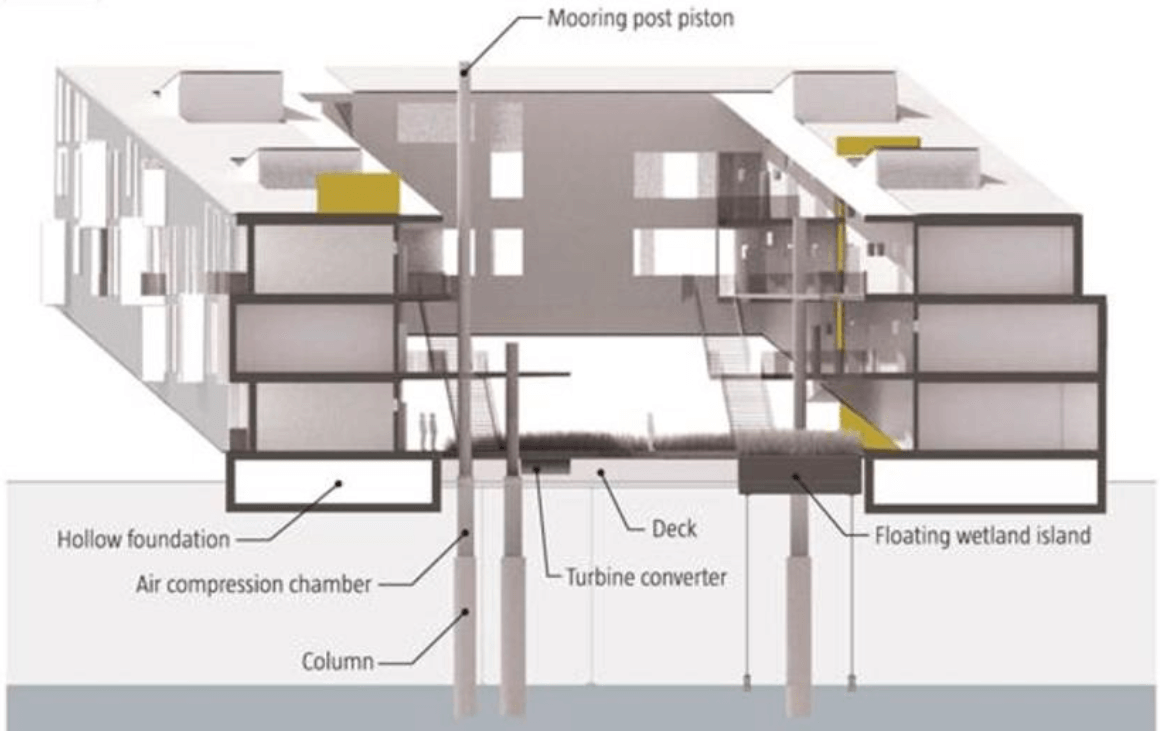

The team’s designs have gone global, with showcases ranging from exclusive floating islands in Dubai and the Maldives for the superrich, to more modest designer homes in Europe and the United States, to projects like the floating container, called City App, that will serve as an education center in the poorest neighborhoods in Asia.

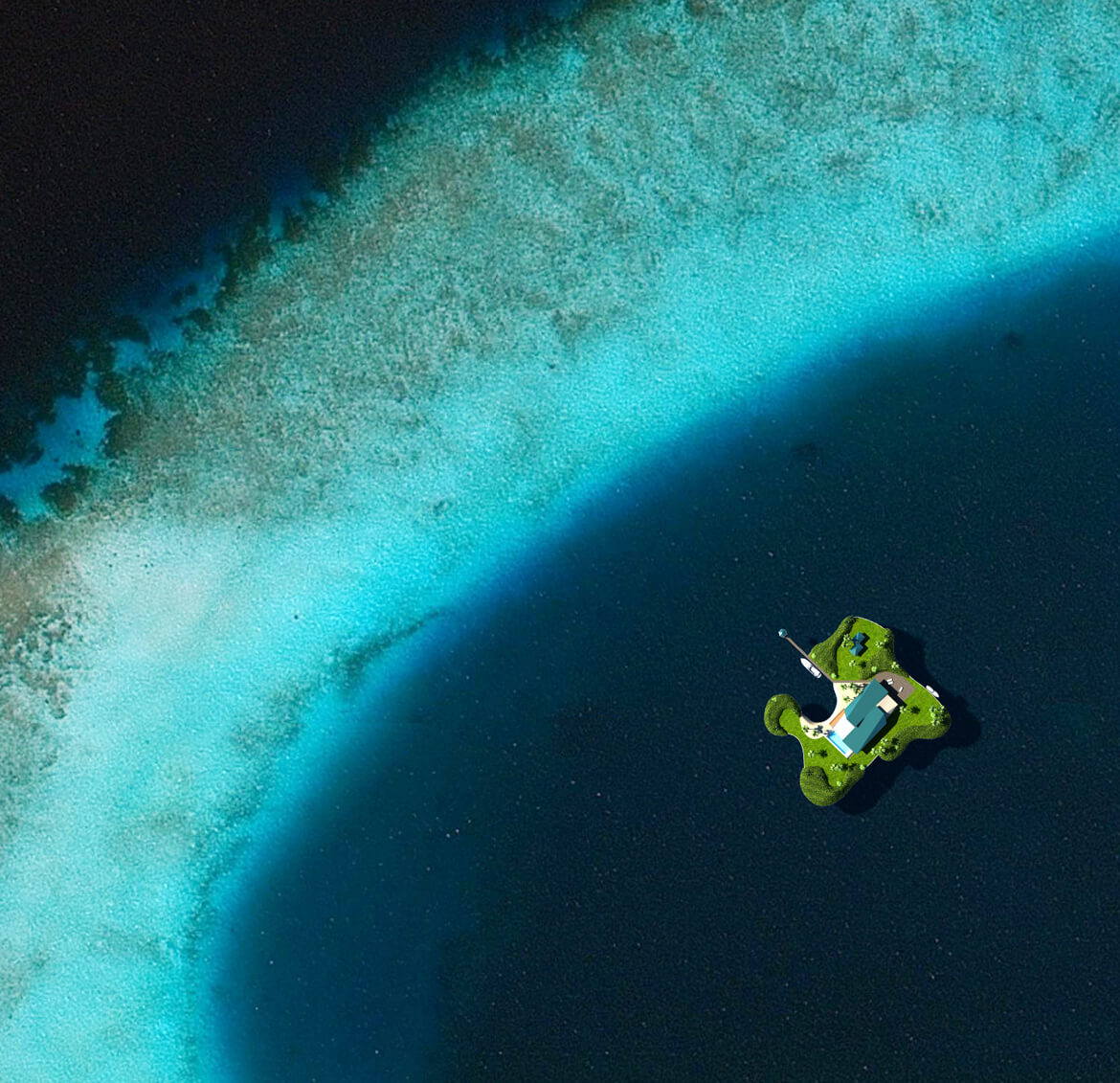

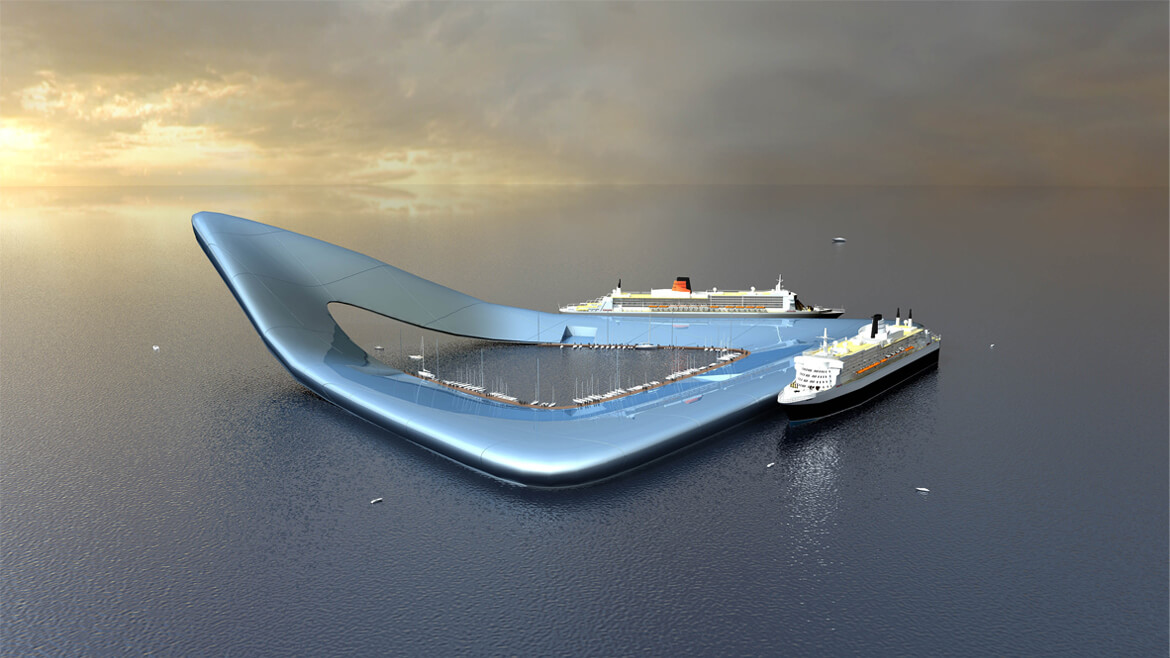

A rendering of a floating private island that can be moved around to suit the owner’s desires.CreditWaterstudio.nl and Amillarah Private Islands

Mr. Olthuis was a candidate for Time Magazine’s list of the 100 most influential people in 2007, and he has been described as a visionary in the media. The BBC dubbed him the “Floating Dutchman” when featuring his plan to build a floating block in Naaldwijk, the Netherlands.

“He was really one of the first architects who saw that building on water could develop a whole new design language,” said Tracy Metz, an American journalist based in the Netherlands and a co-author of “Sweet & Salt: Water and the Dutch” (2012).

Although live-aboard boats and then houseboats have existed for centuries, the modern floating house is a relatively recent invention, with new materials and methods allowing for full-height construction without the loss of stability or the risk of intruding moisture.

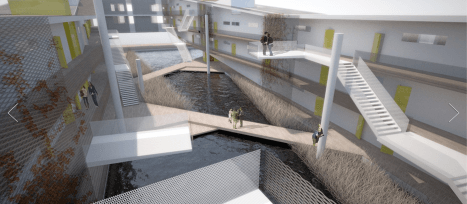

The buildings are constructed on a floating foundation (sometimes stabilized by fixed stilts), which makes them flood-proof, affordable and independent of expensive real estate, although obtaining building permits can be tricky.

Perhaps most important for the slums of Dhaka, the units — which can house amenities like internet terminals, toilets and showers, large-scale water filtration, medical clinics, community kitchens and workshops — can be moved easily to where they are needed most.

Koen Olthuis CreditWaterstudio.nl

“If I were to build only floating islands for the wealthy, I would only make 150 happy people in the next 20 years,” said Mr. Olthuis, 45, who is the grandson of both an architect and a shipbuilder. “If we use this technology also to upgrade slums, we can change the lives of millions.”

As for most of Waterstudio’s other clients, the top draws are the crisp, elegant and open designs, the water views, and — for those with pockets deep enough — the optional private beaches.

The first units of his high-end Oceana project in Dubai are to be delivered next summer. For the project, Mr. Olthuis and Dutch Docklands, the development firm he co-owns, are designing and building 33 islands of 11,000 square feet that support custom-built villas of up to 5,500 square feet each, at an estimated total project cost of $170 million.

The villas themselves resemble smaller houses he has designed in the Netherlands. With open spaces and barely-there transitions between the indoors and the outdoors, his designs are airy, light and modern. The undersides of the islands are equipped with anchor points for marine life that resemble holds on artificial climbing walls, leading to a collaboration with Ocean Futures Society, established by Jean-Michel Cousteau, the son of the explorer Jacques Cousteau.

Christie’s real estate, which is acting as a broker for the units, notes that they can be transported around the globe. Depending on the level of customization and enhancements, the islands will sell for an estimated $5 million.

A rendering of City App, a floating cargo container that can be used to deliver essential services to areas in crisis. CreditWaterstudio.nl

For those on a tighter budget, Mr. Olthuis is set to help reconvert on-the-water living spaces in Weehawken, N.J., just south of the Lincoln Tunnel, on the Hudson River. The first phase of the project focuses on “livable yachts,” which are scheduled to go on the market late next year for slightly less than nearby condos, according to Steve Israel, the developer.

In Bangladesh, the City App aims to bring services to the most affected areas of a large and flood-prone slum. It is the first time Mr. Olthuis has brought his ideas to bear in development work and is almost entirely funded by a foundation he set up that receives funding from Dutch partners.

The floating structure that will pioneer the program was built this year in a yard in Helmond in the south of the Netherlands, nearly 5,000 miles from Dhaka, and features two rows of computers and benches. Four other models are now being built to bring other urgently needed services to Dhaka, although none of the units will consist of actual dwellings.

While he is mostly known in design circles for his open glass constructions, Mr. Olthuis sees a broader mission. He is also an academic member of the flood resilience group at Unesco-IHE in Delft, a water research institute.

In his version of the future, cities will make better use of their water surfaces. In some cases, they will have no choice. Mr. Olthuis envisions public buildings like schools, stadiums and even parks being moved to different waterside neighborhoods according to need.

“In 20 years,” he said, “cities are going to be different than today.”

Photo by Marcel van der Berg

Photo by Marcel van der Berg