Olthuis: ‘Bouw amfibische wijken in overstromingsgebieden’

By Architectenweb

September.5.2016

Over de hele wereld ontwerpt hij drijvende gebouwen, zelfs hele drijvende wijken; architect Koen Olthuis van Waterstudio.NL. Op donderdag 15 september geeft hij op Architect@Work een lezing over de mogelijkheden van drijvende steden. Architectenweb hield met de architect een voorgesprek.

“De steden die we al eeuwenlang op het land bouwen volgen ook maar een concept”, begint architect Koen Olthuis van Waterstudio.NL. “Het is een bewezen concept, maar ook een die niet optimaal functioneert. Onze boodschap is: kijk ook eens naar water en welke mogelijkheden dat biedt om tot een andere stedenbouw te komen.”

Water biedt de stad in Olthuis’ optiek veiligheid, ruimte en flexibiliteit. Om met dat laatste aspect te beginnen: met de verplaatsbaarheid van drijvende gebouwen kunnen steden veel minder statisch worden. De tijd die steden nodig hebben om te reageren op veranderende sociaal-economische vragen, de response time zoals Olthuis het noemt, kan dan flink omlaag.

Als voorbeeld noemt Olthuis steden die enkel in een bepaald seizoen gebruikt worden, seasonal cities. Kunnen die gebouwen off-season niet op een andere plek ingezet worden? “Laat steden met het gebruik meebewegen”, benadrukt Olthuis.

Dat sommige steden dicht bebouwd zijn, betekent volgens hem nog niet dat ze ten volle gebruikt worden. “Ik noem dat de efficiency van het gebruik.” Sommige functies kunnen op het water – als verplaatsbaar gebouw – intensiever gebruikt worden dan wanneer ze op het land zouden blijven.

In Libanon werkt de architect momenteel aan een drijvende woning die uit twee U-vormen bestaat. Hierbij heeft de buitenzijde van de U-vorm een gesloten gevel en de binnenzijde een open gevel. De toekomstige bewoners kunnen straks met beide bouwdelen spelen en ervoor kiezen om de woning volledig gesloten te houden, deze deels te openen, of deze helemaal te openen. Zo kunnen de bewoners bijvoorbeeld inspelen het veranderende klimaat door het jaar heen. Van volledig gesloten naar volledig geopend kost volgens Olthuis maar een paar uur tijd.

Amfibische steden

Wat betreft waterveiligheid vindt Olthuis het interessant wat momenteel in steden als Bangkok, Tokyo en Shanghai gebeurt. Het water heeft daar meer ruimte nodig. Daarom zijn er veiligheidszones ingesteld die nog niet ontwikkeld kunnen worden. Omdat ze bijvoorbeeld eens in de zoveel tijd onder water lopen. “Amfibische wijken of steden kunnen daar een uitkomst zijn.”

Een permanent drijvende woning biedt niet voor iedereen het gewenste comfort, geeft Olthuis toe. De meeste mensen wonen toch het liefst aan een straat met een eigen tuin. Een woning die normaal gesproken op de grond staat, maar bij een overstroming bijvoorbeeld eens in de vijf jaar korte tijd drijft, kan dan een uitkomst zijn.

“De grootste bedreiging in Nederland komt niet van de stijgende zeespiegel, maar van hoge waterstanden in de rivieren en hevige regenval”, stelt Olthuis. “Een aantal van de meer dan 3.500 polders in ons land zouden we daarom in moeten richten als noodopslag voor water. Hier kunnen vervolgens amfibische wijken gerealiseerd worden.” In China en Thailand werkt Olthuis al aan plannen voor dergelijke wijken.

Kansen in Nederland nog onbenut

Ondanks dit alles is het in Nederland de afgelopen jaren opvallend stil rond het bouwen op water. In Rotterdam wordt een drijvende boerderij gebouwd, in Amsterdam worden enkele tientallen waterkavels op de markt gebracht voor particuliere woningbouw. “Onder de 70.000 woningen die jaarlijks in Nederland gebouwd worden zijn misschien honderd waterwoningen.”

“Nederlandse ontwikkelaars zijn lui”, constateert Olthuis. “Nederland is op dit punt gewoon meer een innovatieland dan een uitvoerland.” De hele wereld bekijkend is de architect echter zeer optimistisch over drijvende architectuur. Overal is daar grote interesse in.

Richting architecten heeft Olthuis ook een boodschap: “Zie water als een extra ingrediënt in de stedenbouw dat veiligheid, ruimte en flexibiliteit biedt.”

Architect@Work vindt plaats op woensdag 14 september en donderdag 15 september in Rotterdam Ahoy. Als mediapartner heeft Architectenweb rond het thema architectuur en water een gevarieerd lezingenprogramma samengesteld. Binnen dit programma geeft architect Koen Olthuis van Waterstudio.NL op donderdag 15 september om 17:30u een lezing met de lengte van een uur.

De lezingen tijdens Architect@Work zijn gratis bij te wonen. Registreer je wel van tevoren even. Ga naar www.architectatwork.nl, klik op de knop Gratis Bezoekersregistratie en registreer je met de code 455.

Floating Sea Wall one of 365 top initiatives of 2015

Waterstudio’s Floating Sea Wall is choosen as one of the 365 initiatives in 2015 that will reinvent our world.

Flotter vers Léau-dela

By Gabrielle Anctill

Esquisses

2016 volume 27 nr 1

Projets exemplaires

Carré d’eau

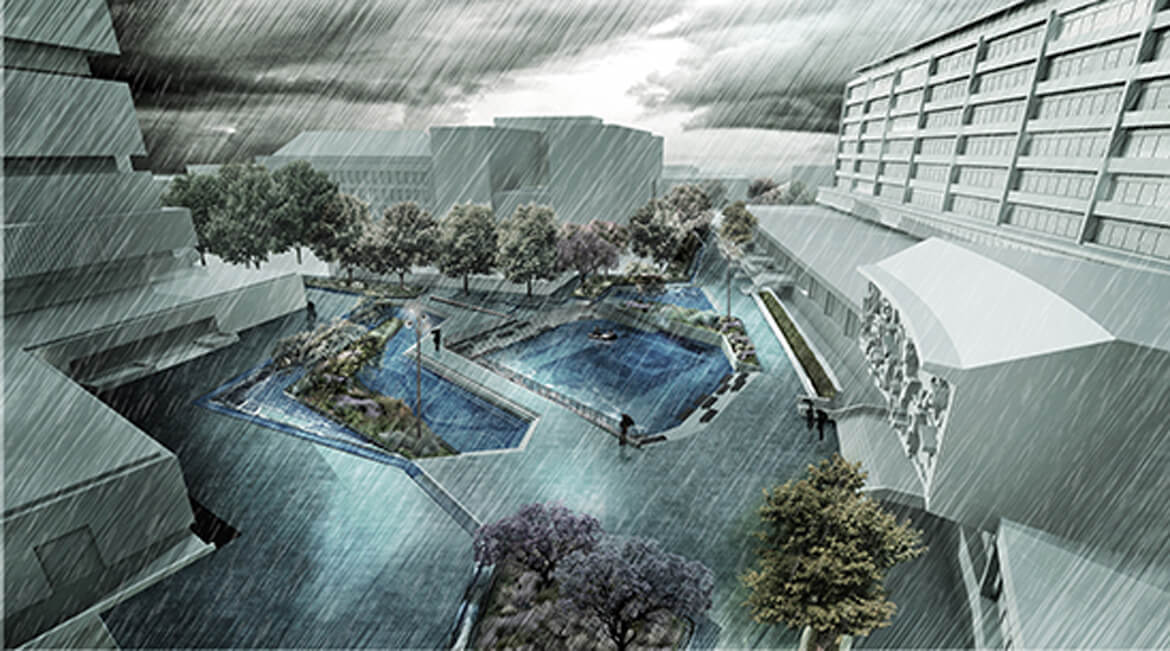

Waterplein (square d’eau), Rotterdam (Pays-Bas), De Urbanisten. Illustration: De Urbanisten

L’ennemi des villes de demain sera l’eau. En première ligne, Rotterdam aux Pays-Bas, qui doit se préparer à combattre les pluies torrentielles causées par les changements climatiques. Pour vaincre les flots, une arme : la place publique.

Gabrielle Anctil

Plutôt qu’une catastrophe à prévenir, la Ville de Rotterdam a décidé de voir les changements climatiques comme une occasion à saisir. C’est pourquoi elle a mandaté en 2005 la firme de recherche urbaine et de design De Urbanisten pour trouver des solutions novatrices en matière de gestion de l’eau. De ces réflexions a émergé l’idée du waterplein ou « square d’eau », une place publique servant aussi de bassin de rétention des eaux.

« La mission du square est de réconcilier la population avec l’eau. Nous voulions créer la même magie que lorsqu’un enfant joue dans une flaque d’eau », explique Dirk Van Peijpe, ingénieur et cofondateur de la firme. Un premier spécimen, le Waterplein Benthemplein, a vu le jour en 2013. Composé de trois bassins de différentes profondeurs, le plus profond faisant office de terrain de basketball, il est conçu pour servir principalement d’espace public. La communauté, qui a participé pleinement à sa conception, se l’est rapidement approprié : en plus des sportifs et autres flâneurs, on peut même y croiser des fidèles assistant à un baptême, gracieuseté de l’église avoisinante.

Lors d’une averse, les trois bassins servent à stocker l’eau de pluie. Avec style. « Nous avons voulu mettre l’accent sur le design », précise Dirk Van Peijpe. Ainsi, les gouttières en acier inoxydable qui transportent l’eau depuis les bâtiments adjacents vers les bassins sont assez larges pour accueillir les planchistes par temps sec. D’autres détails permettent de contrôler la façon dont l’eau atteint les bassins, pour rendre le tout le plus spectaculaire possible. Une fois les égouts libérés, l’étang cède de nouveau l’espace à la place publique.

Le square d’eau est un concept qui porte ses fruits : la firme en planifie déjà un deuxième dans la ville de Tiel, toujours aux Pays-Bas. « La beauté du square, c’est que nous avons repris une idée simple : l’eau descend », souligne Dirk Van Peijpe. Comme quoi certaines idées novatrices coulent de source…

Soigner contre vents et marées

Hôpital Spaulding, Boston (États-Unis), Perkins + Will. Photo : Anton Grassl/Esto

Sous sa façade grise, l’hôpital Spaulding est comme Superman dans les habits de Clark Kent. Portrait d’un bâtiment prêt à tout.

Gabrielle Anctil

L’ouragan Katrina qui a frappé La Nouvelle-Orléans en 2005 a causé un choc dans le milieu hospitalier américain. « Le monde médical a vu les hôpitaux hors d’usage et s’est dit : plus jamais », se remémore Robin Guenther, architecte et associée principale chez Perkins + Will, une firme d’architecture américaine. Mais, lorsque l’ouragan Sandy est tombé sur New York sept ans plus tard, les télévisions ont encore une fois relayé les mêmes images.

C’est avec ces leçons en tête que l’architecte s’est attelée à la conception de l’hôpital Spaulding, à Boston. « Notre client était parfaitement conscient de ce qui s’était passé à La Nouvelle-Orléans et voulait construire un hôpital qui résisterait aux effets des changements climatiques », explique Robin Guenther. Situé dans le port, le bâtiment devait absolument être à l’épreuve de la hausse du niveau de l’eau. Une mission de taille, compliquée par la quantité de données avec lesquelles jongler. Élever le bâtiment était une évidence, mais quelle sera l’élévation du niveau de la mer dans 50 ans ? Comment composer en même temps avec les besoins d’accessibilité d’une clientèle à mobilité réduite ?

L’élévation du bâtiment n’est qu’une des multiples caractéristiques qui le préparent au pire : les génératrices sont situées sur le toit, plutôt qu’au sous-sol, emplacement inondable où on les trouve habituellement, les fenêtres peuvent s’ouvrir et la végétalisation des toitures contribue à réduire les îlots de chaleur.

Les architectes ont tenté de penser à tout, sans pour autant faire exploser les coûts. En fait, moins de 1 % du budget total a été consacré aux mesures d’adaptation aux changements climatiques. Pour Robin Guenther, c’est une évidence : « Quand on y réfléchit à l’avance, comme nous l’avons fait, les coûts sont minimes, alors que réaménager un bâtiment déjà construit coûte extrêmement cher. D’où l’importance de parer dès la conception à la prochaine tempête du siècle. »

Il semble bien que l’hôpital Spaulding sera prêt à l’affronter.

Les jardins suspendus de Milan

Bosco verticale (forêt verticale), Milan (Italie), Stefano Boeri. Photo: Paolo Rosselli.

Le rêve de l’empereur Nabuchodonosor II serait-il devenu réalité ? Devant la menace des changements climatiques, l’idée de verdir en hauteur comme à Babylone n’a plus rien de fantaisiste, tel que le démontre le projet Bosco verticale de Milan.

Gabrielle Anctil

En construisant à Milan les deux tours d’habitation du projet Bosco verticale (forêt verticale), l’architecte italien Stefano Boeri ne voulait pas que leur architecture soit uniquement ornementale. « Les bâtiments sont volontairement plutôt sobres, explique le concepteur. Ce qui compte le plus, c’est l’intégration de la nature. »

Les tours de Bosco verticale sont, comme leur nom l’indique, couvertes de végétation. Mais Stefano Boeri a vu plus loin que les toits verts que l’on connaît déjà : sur les balcons des bâtiments poussent de vrais arbres. « En fait, chaque habitant en a deux, plus huit arbrisseaux et 20 plantes. » Beaucoup plus original qu’une cour de banlieue, et surtout, bien plus durable. « Les villes doivent être plus denses, rappelle l’architecte. Nous ne pouvons plus nous permettre de maintenir le rêve de la maison de banlieue. »

Pour Stefano Boeri, la nature a un rôle primordial à jouer dans la lutte contre la pollution des villes. « Les arbres permettent d’absorber la poussière ambiante et le CO2, de minimiser l’impact des îlots de chaleur urbains et de réduire la température à l’intérieur des logements pendant l’été, réduisant du même coup la consommation d’électricité », énumère l’architecte. Une attention toute particulière a d’ailleurs été accordée au choix des arbres afin de maximiser leurs bienfaits. Ainsi, du côté nord, on a sélectionné des essences à feuilles caduques pour laisser le soleil réchauffer les logements en hiver.

Toute originale qu’elle soit, la forêt verticale doit pouvoir être reproduite à moindre coût pour avoir un réel impact. « Il est tout à fait possible de copier-coller l’idée n’importe où dans le monde, à condition de sélectionner des arbres adaptés au climat », affirme Stefano Boeri. L’architecte s’est d’ailleurs vu confier la mission de concevoir une ville de 100 000 habitants en Chine, selon le modèle de ses tours milanaises.

Si l’idée prend racine, les enfants de demain pourront peut-être grimper aux arbres… sur leur balcon.

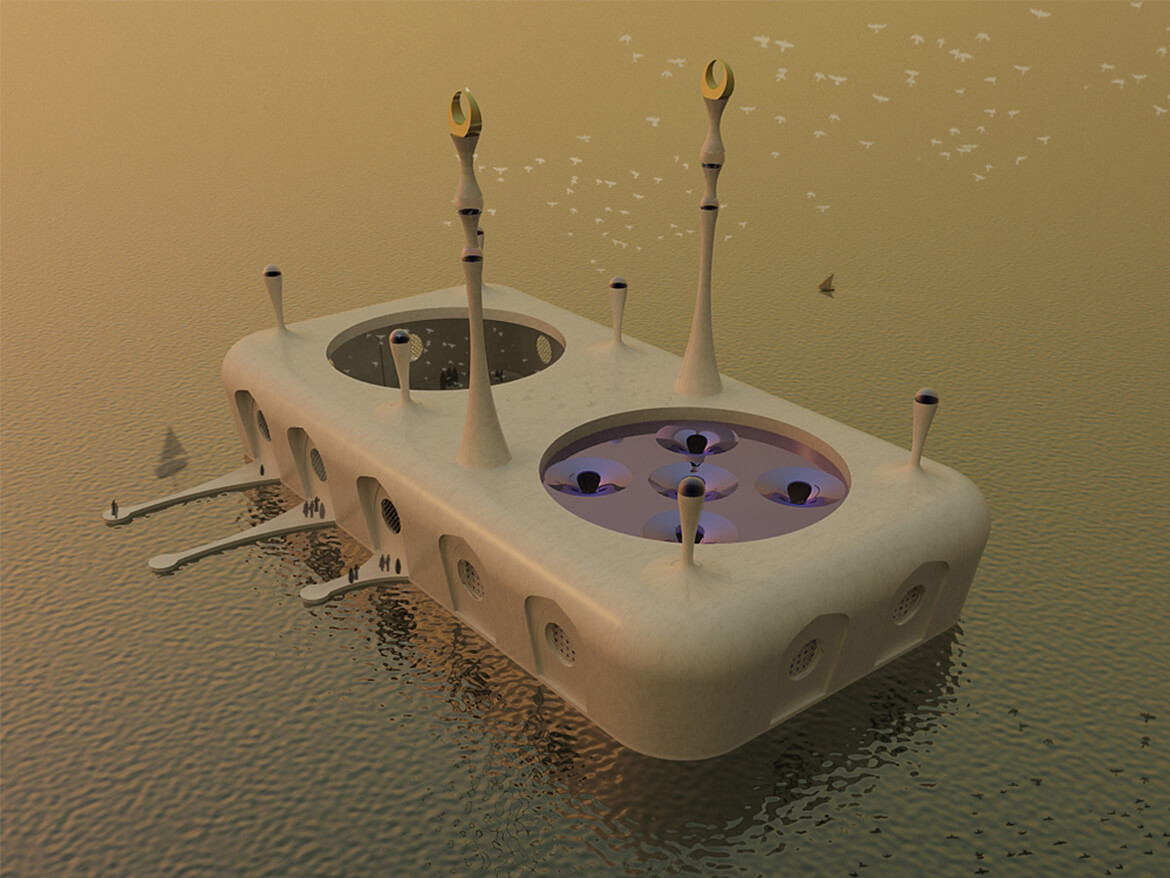

Flotter vers l’au-delà

Concept de mosquée flottante à Dubai (Émirats arabes unis), Koen Olthuis Waterstudio.NL. Illustration : Koen Olthuis – Waterstudio.NL et Dutch Docklands

Une mosquée flottante? L’idée peut sembler loufoque, voire sacrilège. Pourtant, ce type de construction est peut-être la solution idéale pour défier les inondations dans les villes de demain.

Gabrielle Anctil

La firme Waterstudio, de l’architecte néerlandais Koen Olthuis, ne construit que sur l’eau. Quand on lui demande pourquoi, le fondateur répond du tac au tac : « On est en sécurité sur l’eau. Plus besoin de s’inquiéter des inondations. » Pour étonnant qu’il soit, le concept n’a rien de nouveau. « Aux Pays-Bas, on construit sur l’eau depuis plus de 200 ans », affirme l’architecte.

Son expertise a mené Koen Olthuis à travailler à Dubai, aux Émirats arabes unis, où on lui a confié en 2007 le mandat de concevoir un lieu de prière inédit : une mosquée flottante. En plus d’avoir les deux pieds dans l’eau, le bâtiment utilise les flots comme système de climatisation. « En été, les températures montent jusqu’à 50 °C, mais l’eau reste toujours à environ 27 °C », explique l’architecte. L’eau est pompée à travers les murs et passe par le toit avant de retourner dans le golfe Persique, rafraîchissant l’air au passage.

Un bâtiment flottant ne pose-t-il pas des contraintes architecturales importantes ? « Pas du tout, affirme Koen Olthuis. Mise à part la fondation, qui doit s’adapter au type d’écosystème où on la placera, l’architecture est presque identique à celle d’un bâtiment traditionnel. » Le plus gros défi ? Changer la perception du public. À Dubai, l’idée d’une mosquée sur l’eau a causé des remous dans la communauté. « Il y avait des débats à la radio où on se demandait si la mosquée serait assez sacrée ! » se remémore l’architecte. La conclusion ? Oui, mais seulement si elle pointe toujours dans la direction de la Mecque.

Retardé par une économie vacillante, le projet ne verra peut-être jamais le jour. Mais si on en croit Koen Olthuis, les constructions flottantes sont la voie de l’avenir. « On peut construire presque n’importe quoi sur l’eau. Avec l’urbanisation accélérée et les coûts élevés des terrains dans les villes, l’idée de construire sur l’eau devient une évidence. » À quand un quartier flottant au Québec ?

Has Floating Architecture’s Moment Finally Arrived?

By Rachel Keeton

Next City

October.01.2014

Resilient Cities

The Sea Tree, a floating natural habitat. (Photo by Waterstudio)

In a quiet, shady street in Rijswijk, the Netherlands, Koen Olthuis and the design team at Waterstudio are changing the world. From this deceptively nondescript headquarters, Waterstudio is designing the cities of the future. If Olthuis has his way, they will be safer, more flexible and more resilient than current cities. How will he do this? Olthuis is designing floating cities. As we sit down at the table, the busy office buzzing around us, my first question to Olthuis is direct: “How realistic are floating cities?” Olthuis grins and nods, he’s heard this question before.

Floating cities have captivated society’s imagination for centuries, from the development of Venice a millennium ago to Triton, designed for Tokyo Bay by Buckminster Fuller in the 1960s. But it wasn’t until the last decade or so that more fully realized, just-might-actually-happen sea-based urban endeavors have emerged, made more urgent by rising sea levels and rural-to-urban migration. In the last six months, Business Insider, Bloomberg and The Guardian have all run stories asking the same question: “Has the time come for floating cities?”

Olthuis dives right in: “It depends what you mean by ‘floating city.’ If you’re talking about a community of 100,000 in the middle of the sea, we’re probably about 50 years away from achieving that. If you want it to be completely self-supporting, it’s probably going to take another 20 years after that.” Bending over a roll of tracing paper, Olthuis quickly sketches a timeline of floating architecture. If we take it from the present moment, about midway on Olthuis’ sketch, hybrid cities are the next step in this evolution. Built on the edge of the existing city, these developments could easily connect to electrical and sanitation grids. “Technically, this stuff is easy to engineer: we’re already there,” says Olthuis. That makes them more straightforward to regulate and less risky for investors.

It’s the images of sparkling new cities lost at sea that have people raising skeptical eyebrows. “We’re working on a set of guidelines, a toolbox that will ultimately get us to the floating city you imagine. We’re working out these concepts that all give a glimpse of the future, but we have to find out what we need, how it works and what it adds to current urban development. We have to map out the steps to get us from today to the future and have to think about the entire process. And we need that, because if we don’t answer these questions, we get all these architects with beautiful renderings and fantastic ideas, but they don’t tell you the steps in-between and they don’t tell you why. And then your question is, but how realistic is it?”

Listening to Olthuis, it quickly becomes apparent that this scenario is actually incredibly realistic. With the technology and market demand in place, it’s political will and ownership issues that are holding development back. People have trouble imagining an urban future where city halls can be swapped for theaters on opening night, or entire Olympic villages can simply be towed around the world instead of rebuilt every four years. “Our cities today are too static. We make static cities for dynamic societies. We should be cities that can adapt to new demands and external influences. Water gives us three things: it adds more space (in old harbors, rivers, lakes), it’s safer (from storm conditions, rising sea levels) and it’s flexible. If you only construct the buildings you will use for 100 years statically, on land, and construct the buildings you will only use for 20 to 30 years flexibly, on water, then you’ve created a much more adaptable city that can respond to changing needs quickly and efficiently. If someone isn’t happy with their house anymore, they can ship it to someone who needs it in the Philippines.”

Governments are slowing starting to see the potential of this approach. If cities like New York or Tokyo build two to three percent of their development on the water, they can sell this to developers, tax the owners and create a more flexible city. Win-win. Governments are interested in this because it presents a new market for them. While most land is privately owned or already built up, by changing policies to make floating structures available the government expands its real estate. It’s a business model that is attractive because it solves multiple problems. Floating structures can reinvigorate former industrial areas like old harbors or riversides, they can adapt to extreme weather conditions better than traditional structures and they create a profit from space that is currently unmarketable.

Still, the idea of bobbing around permanently makes some people understandably squeamish. If one floating house goes up and down on waves, it may tilt: one half sits on the crest of a wave and the other end is stuck in the trough. This doesn’t happen when you start to build big enough to have a project that is always supported by multiple waves. On the water, the bigger the project, the more stable is it. In fact, floating cities are actually something that works better all around on a larger scale. If Olthuis is designing a watervilla for a single family, he has to calculate all kinds of factors to design a single, site-specific home. This ends up costing a lot more than a traditional house. If he’s designing a community of 10,000 water villas, the price is the same as a comparable urban development.

Moving functional amenities like prisons, stadiums and airports onto the water is already becoming more common as cities try to create more elbowroom for residents. Alvaro Siza’s recently completed chemical plant in Huai’An City, China, was built on the water, and BREAD Studio recently designed a floating cemetery to be rafted off the coast of Hong Kong – a city long on elderly citizens but short on space. Today there’s a floating skate park on Lake Tahoe and floating freshwater pools in the River Thames. There’s even a floating cinema in London by UP Projects, echoing Aldo Rossi’s iconic Il Teatro del Mundo from 1979.

Less whimsical but more crucial are floating developments for informal settlements located on waterfronts or in delta regions that are most vulnerable to rising sea levels. Kunlé Adeyemi’s floating school in Makoko, a picturesque shantytown in Lagos, Nigeria, will provide classroom space for 100 students. The problem with one-off projects like NLE’s floating school, according to Olthuis, is that the Lagos government has been against it from the beginning (it’s been declared illegal), and it’s not even being used because of this controversy. “If you want to really make a difference, it can’t be just one thing. It has to be a system with a sound business model,” says Olthuis.

“I think the current generation of architects really wants to help, they want to make a difference. If you tell the story of one billion people living in slums in places like Thailand, India, Bangladesh — where water is threatening those people and no one is helping them because anything that gets built can be wiped out by the next tsunami — we think, well we have to help those people. The City Apps project — retrofitted shipping containers floating on trash — is a system where we bring in floating schools, sanitation, electricity, water treatment facilities, bakeries, internet cafes, or whatever is most needed. We can connect these floating functions to the slums or disaster sites and they will slowly help upgrade these areas.

We’re investing in this ourselves, by funding the first prototype that will be deployed to Manila. We’ve started a foundation, working with Cordaid, where we lease the City Apps directly. It costs us about €50,000 to design and build a City App in a recycled shipping container, then it gets deployed to wherever it’s needed and there they construct a floating platform out of old plastic bottles and other rubbish. Ultimately, it should be a business model that provides an entrepreneurial opportunity for residents of these areas. It’s cheap — they just pay a small monthly fee — it’s safe, since it goes up and down with the water, and it provides a solution to real problems. If you don’t need it anymore, you just send it back to us and we lease it out to someone else. Next year we’ll have ten, the year after, a hundred, and it will grow to a few thousand containers around the world. Of course, it’s just a small help to these millions of people, but we hope it will act as a model and show that we can shift from giving aid to providing an opportunity for employment.”

On the other end of the inclusiveness spectrum, there are politically motivated projects like the Seasteading Institute’s Floating City. Promoted with viral videos and backed by private donors and crowd funding, these mobile communities are envisioned as new experiments in governance, giving each community total political autonomy over itself. After attending the third Seasteading Institute conference in 2012, Josh Harkinson of Mother Jones summarized the Institute as “a hacker’s approach to government with a Waterworld-esque conception of Manifest Destiny. More than a mere repository for political dreamers, it brings together engineers, scientists, and entrepreneurs of the sort one often finds in the Bay Area: techtopians who might be brilliant or delusional — or both.”

Olthuis accepts that different floating communities may have different goals. “I think we’ve only seen about 10 percent of the ideas that are actually possible in terms of floating architecture. In the next century, we’ll have thousands and thousands of new architects who can think about these possibilities.” Waterstudio calls their floating designs “scarless,” meaning they can be repositioned without leaving any trace of their presence. But the next step is to build designs like the Sea Tree, a floating natural habitat that would give small fish a sanctuary, increase the oxygenation of water, and potentially collect trash as it drifted about.

Olthuis is adamant that we have to embrace the water rather than run from it — we don’t have any other options. “Today, the momentum is there because we see the effects of climate change and we can’t be sure about our safety. We see millions of people moving to the cities and we don’t know where they will live. These issues are finally making people think twice about floating architecture. If we can convince them that it’s also financially profitable and help governments change building regulations, we’ll have a future where it’s normal to see cities that are 95 percent built on land and five percent built on water — just enough to give them the flexibility they need for an uncertain future.” It’s a revolutionary way of thinking about the city: puzzle pieces that can be reconfigured according to changing needs and desires. Olthuis’ concern with marketability and political interest makes his story much more convincing than the glossy renderings popping up on design websites. “Many architects are using technical solutions to approach this problem and just showing us the images without any information. I think a floating city is only something that works when it makes sense economically, socially, spatially — and should also look nice. It should be a normal development that is open to everyone, rather than an alien form for an elite few.” His belief in the advantages of these projects is clear, and the built examples in the Maldives, China and the Netherlands are proof of their viability. Just as it was for Buckminster Fuller 50 years ago, the floating city remains an exciting and mysterious model of urban development. Only now, it’s closer than ever. And Koen Olthuis can tell you exactly how to build it.

Ciudades Anfibias

By Beatriz Portinari

CLUB + RENFE

Los arquitectos del futuro proponen una Atlántida biososteniblecomo respuesta al cambio climático y la utopía de una colonización oceánica.

“El mar no pErtEnEcE a los déspotas. En su superficie, aún pueden ejercer sus inicuos derechos, pelearse, devorarse y transportar todos los horrores terrestres, pero a treinta pies de profundidad, su poder

cesa. ¡Ah, señor, viva usted en el seno de los mares! ¡Solo ahí existe la independencia! ¡Ahí no reconozco señor alguno! ¡Allí soy libre!”. Con estas palabras, Julio Verne convirtió al capitán Nemo y su Nautilus en los pioneros de la llamada “colonización oceánica”, en 1870. Casi 200 años después de 20.000 leguas de viaje submarino, ingenieros y arquitectos ofrecen propuestas viables que van desde hoteles flotantes o flotels a cruceros-residencia para millonarios como The World y finalmente la utopía social y política de las naciones semi-sumergibles que propone el Seasteading Institute.

Pero, ¿por qué querría el hombre vivir en futuristas ciudades acuáticas?

Quizá por placer, por evadir impuestos en aguas internacionales o por pura necesidad medioambiental. Según los expertos en cambio climático y el Informe España: hacia un clima extremo, publicado por Greenpeace en 2014, se espera que a finales del siglo XXI la subida del nivel del mar por el deshielo del Ártico provoque una catástrofe climática y humanitaria que afectará al uno por ciento del territorio de Egipto, el 7% de Países Bajos, el 17% de Bangladesh y hasta el 80% de las Maldivas. En España, las mediciones indican que “durante la segunda mitad del siglo XXI, hasta 202 hectáreas de terreno se encontrarán en riesgo de inundación en la costa vasca. De esta extensión, la mitad corresponde a terrenos urbanizados, tanto zonas industriales como residenciales”. El peligro es real. Las estimaciones más pesimistas dicen que en 2030 habrá 50 millones de refugiados climáticos en el planeta, que ascenderían a 200 millones en el año 2050. ¿Qué hacer con esta población sin tierra? Más allá de previsiones, la evidencia está en el archipiélago de Kiribati, al noreste de Australia, donde 100.000 habitantes buscan territorio para trasladar todo un país porque el suyo ha comenzado a desaparecer bajo el mar. El gobierno de Kiribati ha comprado terreno en las islas Fiji para instalar a su población e incluso se ha planteado los diseños anfibios de uno de los arquitectos más preocupados por el medio ambiente, Vincent Callebaut, autor de los prototipos acuáticos Lilypad, Physalia y el más reciente Aequorea.

‘aRQuibiÓTica’ conTRa El cambio climáTico

“La anticipación urbana es fundamental para crear la ciudad del mañana, que considero imprescindible en la transición energética. Lo que llamo ‘arquibiótica’ es la solución

biotecnológica de la arquitectura a la crisis ambiental que sufrimos. Me inspiro en el biomorfismo, el biomimetismo y

la biónica, donde la ingeniería puede repetir esquemas de la naturaleza y aprovechar las nuevas tecnologías de comunicación”, explica Callebaut, a quien el Ayuntamiento de París

acaba de encargar el rediseño de la ciudad. De momento, sus audaces prototipos todavía no han encontrado océano donde iniciar la revolución verde.

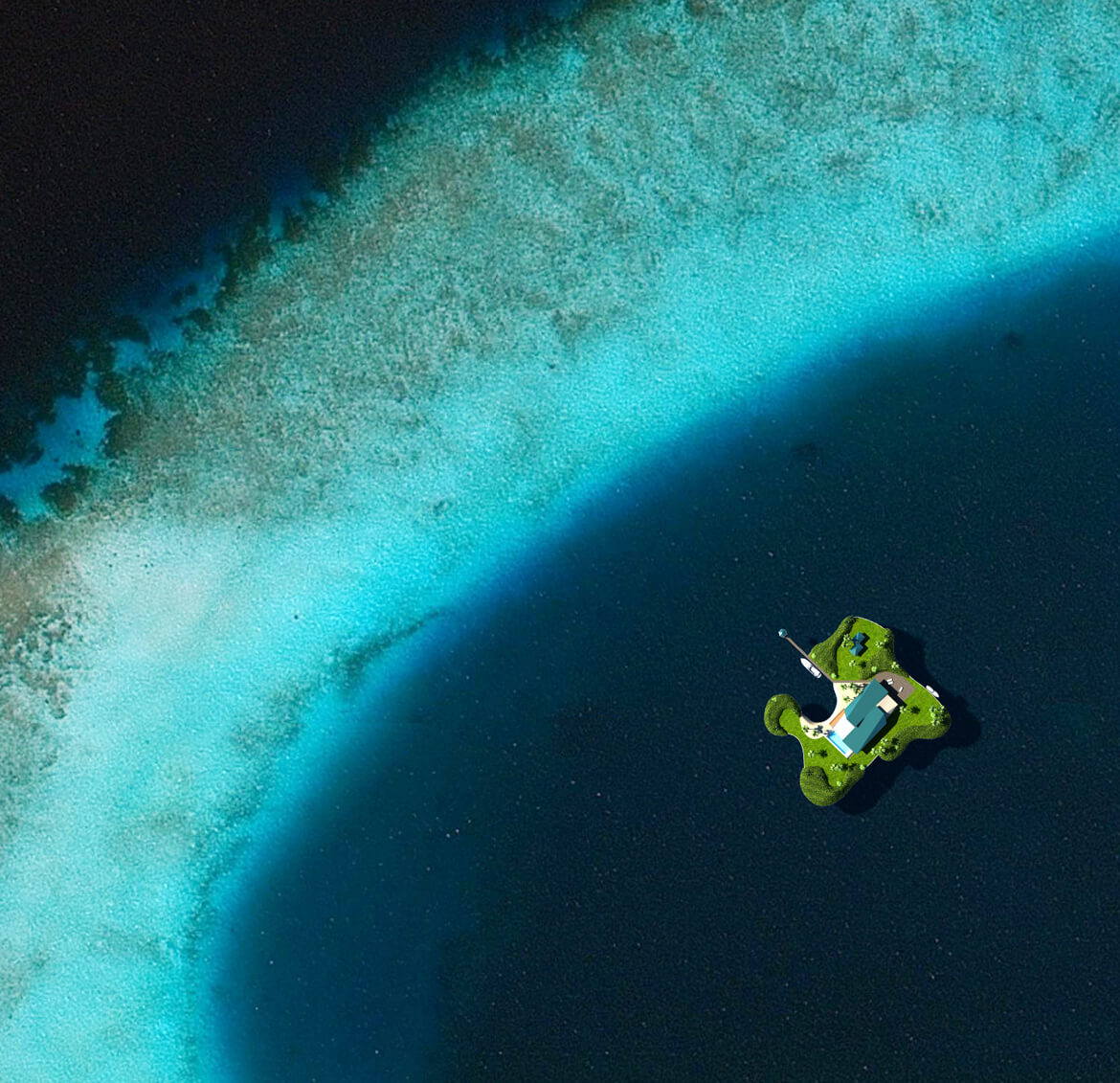

Quien sí ha comenzado la construcción real de un atolón artificial para salvar a su población del mar es el Gobierno de las islas Maldivas, que ha firmado una alianza comercial con la empresa holandesa Dutch Docklands, experta en ganar terreno al agua. Si el entorno paradisíaco de las Maldivas va a desaparecer bajo el mar, nada mejor que empezar a construir una réplica flotante para mantener el turismo. Para ello se ha encargado el proyecto The 5 Lagoons al estudio de arquitectura Waterstudio, que dirige Koen Olthius, considerado “uno de los 100 eco-arquitectos que cambiarán el mundo” y que apuesta por el paso de las ciudades verdes a las ciudades azules sobre el agua. “No debemos tener miedo al posible aumento del nivel del mar, sino verlo como una oportunidad para mejorar nuestras ciudades. Si la costa española se puede ver afectada, debería empezar hoy mismo a considerar soluciones. Estas plataformas flotantes deberían ser eco-sostenibles, más duraderas y flexibles”, cuenta Olthius. El arquitecto va más allá e imagina “bellos parques en el agua, dinámicos, capaces de cambiar de forma y función en cada estación; el turismo ha sido siempre muy importante en la economía española y creo que estas extensiones flotantes podrían atraer más turistas.

Podría aportar al mismo tiempo seguridad y prosperidad a la costa. La tecnología está disponible, sólo sería necesario que fuera económicamente viable”.

El Seasteading Institute, creado en 2008 con importantes inversores como Peter Thiel, fundador de PayPal, va más allá y propone ciudades-estado independientes en aguas internacionales. Sin embargo, su utópico proyecto Floating City aún no ha visto la luz. “Técnicamente las ciudades anfibias son viables, pero deberían responder a una necesidad económica, legal y política real porque de lo contrario el proyecto no es rentable. Si tienes una plataforma que no pertenece a ningún país, no puedes defenderte de ataques piratas, por ejemplo. Para el problema del cambio climático existen soluciones más baratas como se ha visto con el relleno de tierra que está haciendo Singapur en su costa”, advierte el Ingeniero Naval y Oceánico, Miguel Lamas, experto en plataformas flotantes y antiguo colaborador del Seasteading Institute. En su tesis Establecimiento de comunidades autónomas en alta mar: opciones presentes y evolución futura hace un análisis realista de los posibles escenarios. Aunque estas comunidades en alta mar serían beneficiosas porque fomentarían el uso de las energías renovables de origen marino y la protección del hábitat oceánico, hoy por hoy no existe economía ni sociedad que respalde a corto plazo un costoso proyecto como las Ciudades Flotantes autónomas. Parece que la utopía de la colonización oceánica tendrá que esperar.

Koen Olthuis one of fifty innovators of the 21th century

Koen Olthuis selected as one of the Fifty Under Fifty innovators of our time. After a world-wide search of 50 top architecture and design firms by the editors, lead author Beverly Russell along with Eva Maddox and Farooq Ameen help bring together a unique body of work; all partners in these firms will be 50 years old or under at the time of publication, and represent a forward-thinking generation of creative people, aware of global issues that urgently need solutions through imaginative design.

A distinguished five-person jury presided over the final selection: Stanley Tigerman, founding partner, Tigerman McCurry, Chicago; Ralph Johnson, design principal, Perkins+Will, Chicago; Jeanne Gang, founder Gang Studio, Chicago; Marion Weiss, founding partner, WEISS/MANFREDI, New York; and Qingyun Ma, Dean of Architecture, University of Southern California, and founder MADA s.p.a.m., Shanghai and Beijing.

The innovators featured in this impressive volume share with us, and the world, their desires for exponential learning; designs are illuminated with full-color photography and detailed illustrations, helping to showcase the innovators’ individual curiosities, imaginations, and talents. This material shows how they bridge disciplines, respect cultural norms, respond to human needs regardless of costs, and how they adopt team transparency in their passion to create and solve problems with a clear mission.

This highly anticipated book showcases honorees located across many different countries, including Bangladesh, Belgium, Brazil, China, Germany, India, Ireland, Japan, Mexico, The Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Thailand, Turkey, and the United States. Significantly, a quarter of these innovators are women, representing the elevated leadership of women in architecture and design.ᅠ