La Vanguardia Magazine, Eva Millet, May 2014

En el 2001 se sumergió la primera piedra de la llamada Palm Jumeirah: la más pequeña de las tres islas artificiales del proyecto Islas Palm, frente a la costa de Dubái. El emirato del golfo Pérsico empezó el siglo XXI inmerso en un frenesí constructor que no sólo preveía dominar el desierto y levantar el edificio más alto del mundo, sino también expandirse hacia el mar. En un lugar donde hasta hacía poco la hoja de palmera era el material constructivo básico, la silueta de este árbol, incrustada sobre el agua, formando la primera de las islas, se convirtió en una demostración de fuerza para unos y de megalomanía para otros.

En el 2001 se sumergió la primera piedra de la llamada Palm Jumeirah: la más pequeña de las tres islas artificiales del proyecto Islas Palm, frente a la costa de Dubái. El emirato del golfo Pérsico empezó el siglo XXI inmerso en un frenesí constructor que no sólo preveía dominar el desierto y levantar el edificio más alto del mundo, sino también expandirse hacia el mar. En un lugar donde hasta hacía poco la hoja de palmera era el material constructivo básico, la silueta de este árbol, incrustada sobre el agua, formando la primera de las islas, se convirtió en una demostración de fuerza para unos y de megalomanía para otros.

En Panamá, la llamada Cinta Costera, 26 hectáreas de terreno ganadas al mar, es ya una realidad: incluye una nueva autovía y numerosas zonas verdes. En el Mediterráneo, el Principado de Mónaco, un densísimo paraíso fiscal con mucha demanda de vivienda, ha decidido seguir ganando terreno al mar en este siglo, creando un nuevo barrio en la zona de Portier. En total, una superficie de seis hectáreas que incluirá una lujosa zona residencial y comercial y una marina para los yates.

El proyecto, una apuesta personal de Alberto II, el actual príncipe, ha sido otorgado a una constructora francesa y a tres despachos de arquitectura, entre los que destaca el del premio Pritzker Renzo Piano. No han trascendido planos ni imágenes virtuales, pero se sabe que la inversión superará los mil millones de euros y el proyecto se completará hacia el 2024. Una iniciativa similar, del doble de extensión, fue diseñada en el 2008 por los también arquitectos estrella Daniel Libeskind y Norman Foster. Se abandonó la idea debido a la crisis financiera mundial y, también, a motivos medioambientales.

El medio ambiente no parece ser una preocupación en los Emiratos Árabes: para sentar las bases de las dos primeras Islas Palm se requirieron casi 300 millones de metros cúbicos de arena, dragada del fondo del mar. Las obras fueron tan agresivas que, según diversos estudios realizados, se ha dañado de forma casi irremediable el ecosistema marino, además de llenar de cieno las otrora cristalinas aguas del golfo de Dubái.

La tercera fase, la llamada Palm Deira, precisó un volumen aún mayor de materiales, mientras que el archipiélago El Mundo (300 islas artificiales que conformaban la silueta de los países del planeta) arrojó otro gran número de toneladas de piedras y arena al fondo del mar antes de pararse, también por causas financieras, pero no medioambientales.

De todo lo desarrollado en menos de una década en el mar frente a Dubái, solamente está habitado el Jumeirah, donde se construyeron –y vendieron a precios astronómicos– decenas de villas y apartamentos. Según el diario inglés ‘The Daily Telegraph’, sus residentes se quejan hoy de las igualmente astronómicas facturas de electricidad que pagan por el aire acondicionado, que han de tener encendido de forma casi permanente. También se han dado problemas ocasionales con la fontanería que les han obligado, en más de una ocasión, a utilizar los baños públicos de uno de los centros comerciales existentes. La Palmera cuenta, por supuesto, con varios de estos complejos, además de las marinas y los hoteles de lujo que se publicitaron con el proyecto.

Lujo es un sustantivo que se repite constantemente en la actual tendencia de construir sobre el mar. En el siglo XXI vivir sobre el agua es signo de exclusividad. Algo chocante si se tiene en cuenta que (Venecias aparte) a lo largo de la historia, este hábitat ha sido sinónimo de precariedad. En Asia, los más pobres, los marginados, son quienes han vivido tradicionalmente mecidos por las mareas: como los tankas, que habitan en juncos en las zonas costeras del sur de China, Hong Kong y Macao y a quienes se les llama “los gitanos del mar”. En el Pacífico, los bajaut laut o “nómadas del mar” son una tribu remota y pobre que habita en barcazas de las que prácticamente no descienden o en cabañas construidas sobre postes a varios kilómetros de la costa.

El sistema de los postes ha sido copiado en muchos centros turísticos de lugares como la República de las Maldivas, donde las ristras de coquetos bungalows sobre las aguas del Índico se han convertido en sinónimo de vacaciones soñadas. Abundan en todo este país, compuesto de 1.200 islas, y es un modelo que se ha exportado a otros destinos similares.

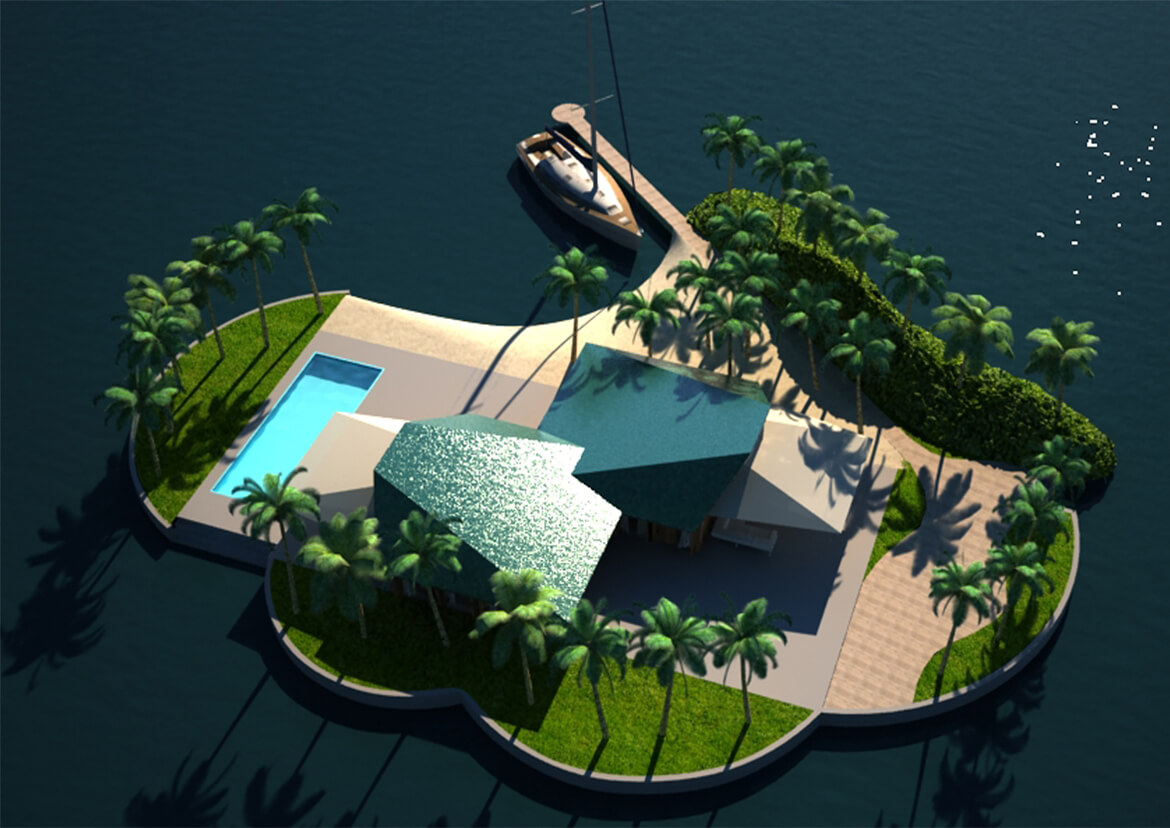

Ahora, en una vuelta de tuerca, el Gobierno de Maldivas ha puesto en marcha un proyecto bautizado Las 5 Lagunas, que pretende urbanizar cinco atolones del paradisiaco archipiélago con infraestructuras flotantes. Se promoverán desde viviendas de lujo e islas privadas hasta un campo de golf y un centro de congresos, todo flotante. El proyecto se ha encargado a la empresa holandesa Dutch Docklands, especializada en estructuras de este tipo.

La compañía, con sedes en Amsterdam, Dubái y Maldivas, confirma vía correo electrónico que ya se ha iniciado la construcción de la primera fase: “Se llama La Flor del Océano y consiste en 185 impresionantes casas sobre el mar, conectadas por un embarcadero, formando esta flor, que es el símbolo nacional de las Maldivas”, explica Klaas Boon, uno de sus responsables. Añade que las viviendas están a la venta “bajo la exclusiva etiqueta de Christie’s International Real Estate” y que los precios se sitúan “sobre el millón de dólares por villa”.

La compañía, con sedes en Amsterdam, Dubái y Maldivas, confirma vía correo electrónico que ya se ha iniciado la construcción de la primera fase: “Se llama La Flor del Océano y consiste en 185 impresionantes casas sobre el mar, conectadas por un embarcadero, formando esta flor, que es el símbolo nacional de las Maldivas”, explica Klaas Boon, uno de sus responsables. Añade que las viviendas están a la venta “bajo la exclusiva etiqueta de Christie’s International Real Estate” y que los precios se sitúan “sobre el millón de dólares por villa”.

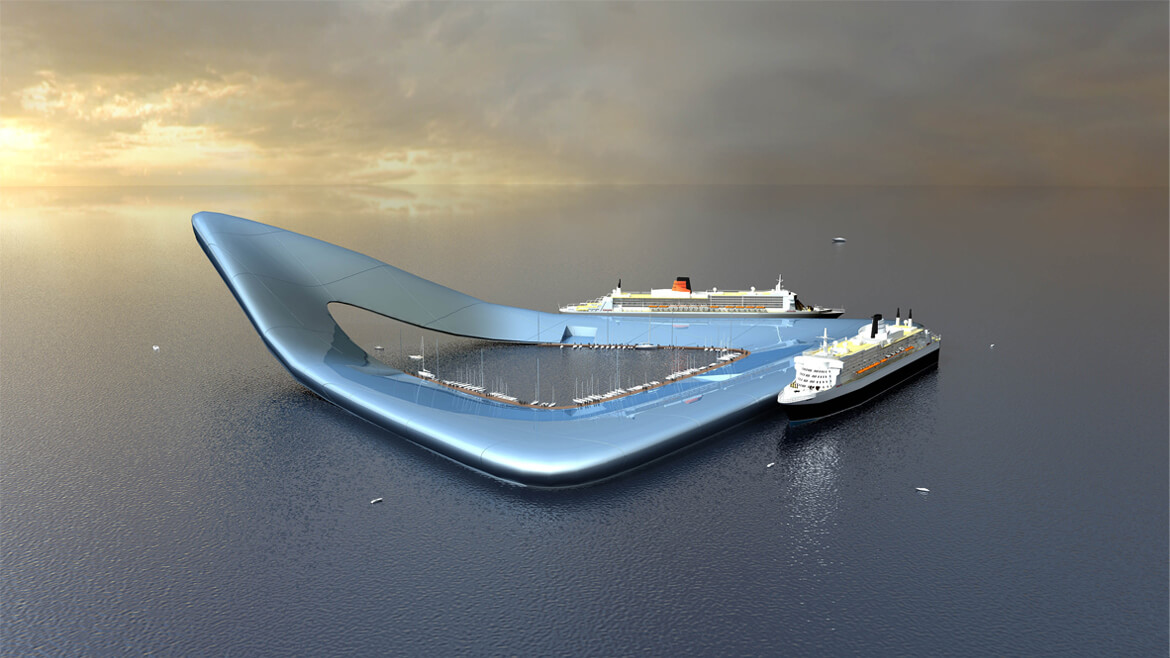

El arquitecto del proyecto es el también holandés Koen Olthuis, cuya compañía, Waterstudio, se describe como la primera firma de arquitectura dedicada en exclusiva a “vivir en el agua”. Olthuis, de 42 años, se define como un pionero en “un nuevo mercado” que lleva la arquitectura “más allá de la costa, creando nuevas posibilidades flotantes para ciudades en crecimiento por todo el mundo”. La prognosis, explicada desde Waterstudio, es que, hacia el 2050, aproximadamente el 70% de la población mundial va a vivir en áreas urbanizadas. Dado el hecho de que el 90% de las ciudades más grandes del mundo está en la costa, “hemos llegado a una situación en la que estamos obligados a replantear el modo en el que vivimos con el agua”.

Contactado telefónicamente Olthuis, pionero de las islas flotantes, mientras se encontraba de vacaciones en la sólida Mallorca, explica que para él, construir sobre el mar es tanto una moda como una necesidad. “Expandir la ciudad hacia el mar, en casos como Nueva York, Tokio, Hong Kong o Singapur, ciudades cada vez más densas y pobladas, ha sido una necesidad”, explica. “Pero en el futuro las ciudades necesitarán más flexibilidad: las urbes cambian constantemente, por lo que lo interesante sería hacer ciudades flexibles, en el agua: edificios flotantes con distintas funciones, que puedas mover con bastante rapidez según las necesidades”, señala.

Olthuis añade que, dado que cada vez son más la urbes amenazadas por las subidas del agua, si se apuesta por construir edificios que floten, el peligro de inundaciones se minimiza. “Así que creo que construir sobre el mar se basa en tres cosas: la seguridad, el espacio y la flexibilidad –resume–. Aunque también hay una moda, una tendencia, porque los arquitectos y los urbanistas e, incluso, los gobiernos, vemos las posibilidades del agua. Cada vez hay más gente que se interesa por el tema!”.

La idea holandesa resulta, como mínimo, más discreta, comparada con los megaproyectos de Dubái, la isla artificial de Yas, en Abu Dabi (un monumental parque temático y comercial que se empezó a construir en el 2006) o la ambiciosa Pearl City, en marcha en Kuwait (una ciudad que quiere llevar el mar al desierto).

Olthuis asegura que fabricar las estructuras flotantes fuera del sitio y anclarlas al fondo marino es altamente sostenible. “Si un siglo después sacas nuestro proyecto –afirma–, no quedarán cicatrices en el paisaje, porque son edificios flotantes. No hay obras, no vertemos toneladas de arena ni dañamos el medio ambiente. Y eso es lo que el Gobierno de las Maldivas busca, porque no quiere estropear lo que atrae a la gente a la islas”.

Los promotores también recuerdan que el archipiélago podría ser uno de los primeros países del mundo en desaparecer por el aumento de los niveles del mar. “Por eso, para ellos, es esencial introducir nuevos modos de construir ciudades sobre el agua”, reiteran los diseñadores holandeses. Que este proyecto es casi la solución a la amenaza del cambio climático se repite como un mantra en la información (tanto gubernamental como privada) sobre él. Aunque, si las aguas suben debido el calentamiento global, no parece que la respuesta más efectiva sea construir villas para multimillonarios en lugares vírgenes como las Maldivas o en islas artificiales como las de Dubái… Pese a la diferencia de escala, en ninguno de los casos aparece la supuesta función social de la arquitectura.

“Sí, es cierto que lo que estamos haciendo en Maldivas está dirigido, por un lado, a los superricos, a la gente que podrá pagarse esas viviendas –admite Olthuis–. Sin embargo, todos los conocimientos tecnológicos que ganamos con estos proyectos podrán aplicarse a otros con función social. Estamos en conversaciones con el Gobierno de Maldivas para llevar a cabo un plan de vivienda asequible para la población de la capital, donde hay serios problemas causados por la densidad”.

Pero estos argumentos no convencen a todos. “Unas islas flotantes son turismo masivo”, asegura, rotunda, Pilar Marcos, la responsable de la campaña de costas de Greenpeace España. “Los atolones son espacios coralinos, supuestamente protegidos, y como no tienen prácticamente terreno, ya que la franja costera es nula para el desarrollo urbanístico, se ha ideado este sistema de chalecitos flotantes que, aunque parezcan muy monos, tienen un impacto que es brutal”, agrega.

Las organizaciones ecologistas como Greenpeace denuncian la mercantilización del medio natural en todo el mundo, donde el mar abierto parece ser la nueva frontera. “No conformándonos con destruir la primera línea de costa, como se ha hecho en España, ahora vamos a ir a ganar terrenos al mar”, denuncia Marcos. Para Greenpeace, casos como el de Dubái, que han tenido unas nefastas consecuencias medioambientales, ya han demostrado que al mar es mejor dejarlo tranquilo. “Se acude a él tratando de buscar más espacio o una confortabilidad en una zona que, como Dubái, es una locura, por la ausencia de agua y de recursos naturales… Es algo aberrante: el querer convertirse en destino turístico a toda costa y que pague el medio ambiente”, indica.

Marcos señala que con estos proyectos, a menudo justificados por motivos económicos, se hace caso omiso al propio sector turístico, que demanda cada vez más espacios protegidos y no masificados. Además, en el Índico, señala, la presencia de nuevas infraestructuras, como casas y hoteles, hace que se pierden las características naturales del mar, “que ya no va a ser tan cristalino como antes…; el desarrollo de los recursos naturales no nos va a sacar de pobres”, concluye. ¿Aunque se insista en su sostenibilidad?

Con esto, advierte la activista de Greenpeace, hay que ir con muchísimo cuidado, pues a la clásica justificación económica para mancillar el medio natural, hoy se le suma la tendencia del ‘greenwashing’, literalmente, “lavado en verde” o vender como ecológico y sostenible algo que no lo es, esté en el Mediterráneo, en el desierto de Dubái o en un atolón de las Maldivas.

Click here for the website

La compañía, con sedes en Amsterdam, Dubái y Maldivas, confirma vía correo electrónico que ya se ha iniciado la construcción de la primera fase: “Se llama La Flor del Océano y consiste en 185 impresionantes casas sobre el mar, conectadas por un embarcadero, formando esta flor, que es el símbolo nacional de las Maldivas”, explica Klaas Boon, uno de sus responsables. Añade que las viviendas están a la venta “bajo la exclusiva etiqueta de Christie’s International Real Estate” y que los precios se sitúan “sobre el millón de dólares por villa”.

La compañía, con sedes en Amsterdam, Dubái y Maldivas, confirma vía correo electrónico que ya se ha iniciado la construcción de la primera fase: “Se llama La Flor del Océano y consiste en 185 impresionantes casas sobre el mar, conectadas por un embarcadero, formando esta flor, que es el símbolo nacional de las Maldivas”, explica Klaas Boon, uno de sus responsables. Añade que las viviendas están a la venta “bajo la exclusiva etiqueta de Christie’s International Real Estate” y que los precios se sitúan “sobre el millón de dólares por villa”.