How floating architecture could help save cities from rising seas

By Kate Baggaley

NBC

From New York to Shanghai, coastal cities around the world are at risk from rising sea levels and unpredictable storm surges. But rather than simply building higher seawalls to hold back floodwaters, many builders and urban planners are turning to floating and amphibious architecture — and finding ways to adapt buildings to this new reality.

Some new buildings, including a number of homes in Amsterdam, are designed to float permanently on shorelines and waterways. Others feature special foundations that let them rest on solid ground or float on water when necessary. Projects range from simple retrofits for individual homes in flood zones to the construction of entire floating neighborhoods — and possibly even floating cities.

“It’s fundamentally for flood mitigation, but in our time of climate change where sea level is rising and weather events are becoming more severe, this is also an excellent adaptation strategy,” says Dr. Elizabeth English, an associate professor at the University of Waterloo School of Architecture in Ontario. “It takes whatever level of water is thrown at it in stride.”

NEW KIND OF FLOOD READINESS

From ground level, amphibious houses look like ordinary buildings. The key difference lies with their foundations, which function as a sort of raft when the water starts to rise.

In some cases, existing homes can be retrofitted with amphibious foundations to give people in flood-prone areas a less costly alternative to moving or putting their homes on stilts, says English, founder of Buoyant Foundation Project, a nonprofit based in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana and Cambridge, Ontario. “What I’m trying to do is to take existing communities and make them more resilient and give them an opportunity to continue to live in the place that they’re intimately connected to,” she says.

There are also new constructions built with amphibious foundations, such as a home designed by Baca Architects on an island in the River Thames in Marlow, England. When waters are low, the house rests on the ground like a conventional building; during floods, it floats on water that flows into a bathtub-shaped outer foundation.

Amphibious architecture isn’t about to displace conventionally designed buildings. But experts say it could become the norm in parts of Virginia, Louisiana, Alaska, and Florida, and other areas that are vulnerable to rising seas. “For some communities this might be a saving grace,” says Illya Azaroff, director of design at New York-based +LAB Architect PLLC and an associate professor of architecture at the New York City College of Technology.

FLOATING HOMES

Other architects are taking things a step further and building on the water itself. The Netherlands is a hotspot for such floating construction. Waterstudio, a Rijswijk-based architecture firm, recently designed nine floating homes for the town of Zeewolde. The homes look a bit like oversized floating houseboats.

Waterstudio has also designed a number of floating homes for Amsterdam’s IJBurg neighborhood. Soon these will be joined by a floating housing complex designed by the Dutch firm Barcode Architects and the Danish firm Bjarke Ingels Group. When construction is completed in 2020, the complex will have 380 apartments as well as floating gardens and a restaurant.

Floating buildings and neighborhoods are not a new idea, of course. Vietnam and Peru, among other countries, have had floating communities for centuries. But floating architecture could allow cities around the world to grow and evolve in new ways, says Waterstudio founder Koen Olthuis.

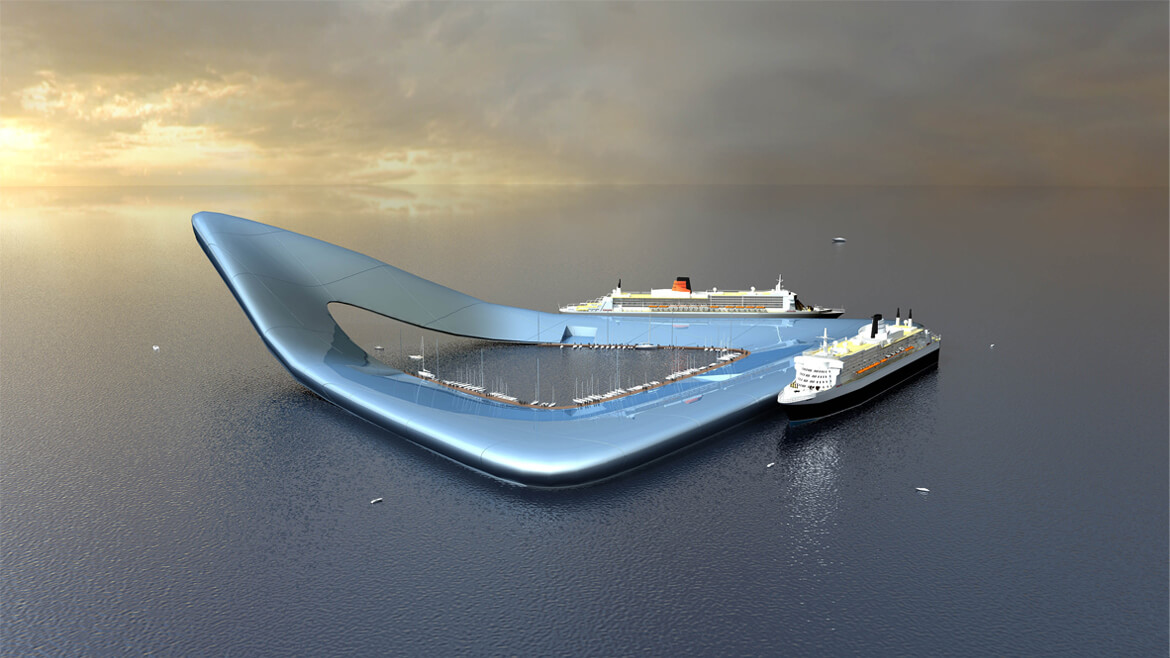

Olthius envisions cities with floating office buildings that can be detached and rearranged as needed. “It can be that you come back to a city after two or three years and some of your favorite buildings are in another location in that city,” he says, adding that buildings might be moved close together to conserve heat and separated when summer arrives.

SPREADING OUT

Floating architecture can do more than prevent flood damage. By allowing the construction of buildings over water, it can give cities additional room to grow. Waterstudio is collaborating with developer Dutch Docklands on a planned community in the Maldives that will include 185 floating villas. The flower-shaped development will have restaurants, shops, and swimming pools.

The firms are also collaborating in the Maldives to build private artificial islands that will be anchored to the seafloor. The idea is to provide new places to live for residents of the low-lying islands, which are at risk of being swallowed up by rising seas. “We will let the commercial project show that the construction can work and then work with the government to help the local community,” Jasper Mulder, vice president of Dutch Docklands, told Travel + Leisure.

The islands are also meant to offer a sheltered new habitat for marine life.

There are also plans for entire floating cities. The Seasteading Institute, a San Francisco-based nonprofit, hopes to attract 200 to 300 residents for a floating village scheduled for completion in the waters off Tahiti by 2020. Homes and other buildings in the community will be constructed atop a dozen or so floating platforms connected by walkways. Eventually, the institute hopes to create communities built from hundreds of platforms with millions of residents.

“I don’t know if amphibious or floating architecture will go that far, but it is within the realm of possibility,” Azaroff says. “The overarching goal is to, one, keep people safe and, two, to allow the natural cycles to continue. Floating architecture allows you to do that in a really profound way that we didn’t have before.”

Med hjälp av cityappar vill arkitekterna på Waterstudio tillgodose grundläggande behov i världens vattennära slumområden. Foto: Sebastian van Baalen

Med hjälp av cityappar vill arkitekterna på Waterstudio tillgodose grundläggande behov i världens vattennära slumområden. Foto: Sebastian van Baalen

De New Water Villa.

De New Water Villa.