By P.Kennedy

Suffolk Construction’s Content

Build smart

September.16.2016

With hurricane season at its peak, we explore how floating homes might help us adapt to bigger storms and rising seas.

The Dutch have a head start when it comes to dealing with water. The extreme weather events and rising sea level that scientists predict this century will affect millions around the globe—most of the world’s largest cities are along the coasts. But that problem has long been acute in the low-lying Netherlands, where two-thirds of the population live in flood-prone areas. Over the centuries, the Dutch have honed technologies—dikes, canals, and pumps—that keep their streets and houses dry.

Now, a new generation of Dutch engineers and architects is modeling another method. Rather than fight to keep water out, they say, why not live on it? The basic idea is not new—hundreds of free spirits live on traditional houseboats in quirky communities like Sausalito, California, and Key West, Florida. But in the Netherlands over the past few years, novel technologies have allowed developers to build roughly a thousand (and counting) stable, flat-bottomed, multi-story homes connected to land-based utilities yet designed to rise and fall with the tides and even floods. House boats, these ain’t.

And this is just the start. The Dutch are thinking bigger, and they’re exporting their floating-home vision worldwide, betting that the rest of us coastal clingers could use it. Some projects exist already, others are on the drawing board or coming soon. Let’s take a look at a few, from the workaday to the fantastical, and from overseas to right here in the States.

Photo by Roos Aldershoff, courtesy of Marlies Rohmer Architects and Urbanists

Photo by Roos Aldershoff, courtesy of Marlies Rohmer Architects and Urbanists

A “normal house” on water

The first of its kind, Waterbuurt (above and top) is a planned neighborhood of about 100 (eventually 165) floating houses in Amsterdam’s IJmeer Lake, part of a freshwater reservoir dammed off from the North Sea in the 1930s. Waterbuurt broke ground—er, water—in 2009, and was largely complete by 2014. Connected by jetties, the structures are three-story, 2,960-square-foot houses built of wood, aluminum, and glass.

And the foundations? Floating concrete tubs. Each house is designed to weigh 110 tons and displace 110 tons of water, which—as Archimedes could tell you—causes it to float. (The bottom floor is half submerged.) To prevent rocking in the waves, the house is fastened to two mooring posts—on diagonally opposite corners of the house—driven 20 feet into the lake bed. The posts are telescoping, allowing the house to rise and fall with the water level. Flexible pipes deliver electricity and plumbing.

Because any crack in the foundation tub could cause the house to sink, there can’t be any joints; builders pour the entire basement in one shot—much like the parking garage of the Jade Signaturecondo complex in Florida. In a facility 30 miles away from the IJmeer Lake site, crews use special buckets that pour 200 gallons per minute to finish all four walls and the floor in a single shift.

Just four months elapse before the entire house is built; then it’s towed by tugboat—30 miles through canals and locks—to the plot. The transportation is a major reason the houses cost about 10 percent more than an average home in Amsterdam, though they’re still aimed at the city’s middle class. The houses were designed by architect Marlies Rohmer, for developer Ontwikkelingscombinatie Waterbuurt West.

Photo by Marcel van der Berg

Photo by Marcel van der Berg

Once secured to its mooring posts, the structure is formally considered an immovable home, not a house boat. (Although owners have the option of naming their waterborne homes as sea captains do. One couple calls theirs La Scalota Grigia—Italian for “The Grey Box.”)

With high ceilings and straight angles, a house in Waterbuurt “feels like a normal house,” wrote a New York Times reporter who toured one. But some residents say they do feel their home swaying when the wind kicks up.

One other drawback, or at least challenge: Residents have to decide before the house is even built where they’re going to place furniture, because that will affect its balance. The walls are built to varying thickness, depending on the layout submitted. What if you inherit a beloved aunt’s piano after you move in? Or have another child and need to buy a bunkbed? To compensate, homeowners can install balance tanks on the exterior or Styrofoam in the cellar, or carefully move furniture around or even deploy sand bags. A bit of a hassle, but perhaps with an eye on rising sea levels, that’s a risk Amsterdammers are willing to take.

Rendering courtesy of architect Koen Olthuis, Waterstudio.NL, and developer Dutch Docklands

Living large on a lake

At the luxury end of the market, there’s Citadel, which aims to be the world’s first floating apartment complex. Construction began in 2014. Citadel uses the same technology as Waterbuurt—floating concrete base, mooring pistons—but on a larger scale, in the sense that this will be one massive deck supporting a multifaceted apartment building, rather than a place for many individual houses to dock. Think of it as Waterbuurt with butlers. (And underwater parking and other amenities).

Citadel was designed by pioneering architect Koen Olthuis’ Waterstudio in partnership with master developer Dutch Docklands. The concrete caisson foundation will measure 240 by 420 by 9 feet, supporting 60 sleek, aluminum-clad apartments in an irregular arrangement that from the air will look a bit like a scattering of stacks of jigsaw puzzle pieces. Palm trees will sprout from courtyards. Green roofs are planned, and the developer hopes to have Citadel use 25 percent less energy than a similarly-sized complex on land.

One thing remarkable about Citadel is the body of water it will float in: a lake that doesn’t exist yet, though it did once. Construction is taking place in a polder, one of the Netherlands’ many low-lying areas that is only dry because pumps work 24-7 to keep the water out. Once construction is complete, the pumps will shut off, and the area will be re-flooded, to 12 feet deep. Eventually, Dutch Docklands plans to build five more complexes in the same un-manmade lake, dubbed New Water.

Rendering courtesy of architect Koen Olthuis, Waterstudio.NL, and developer Dutch Docklands

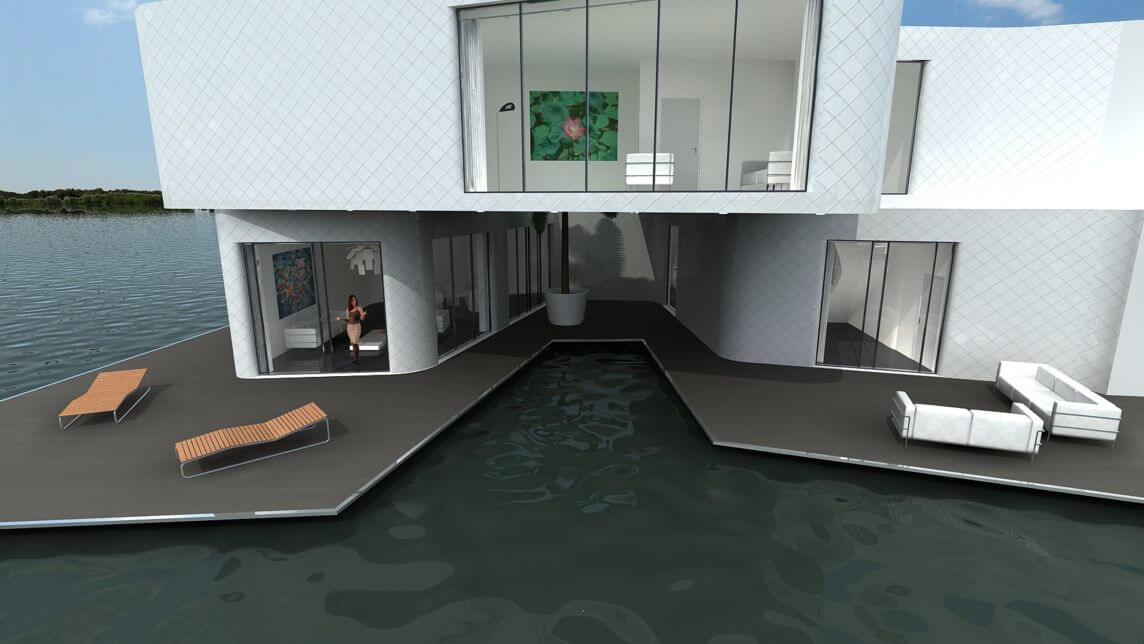

Exporting the vision

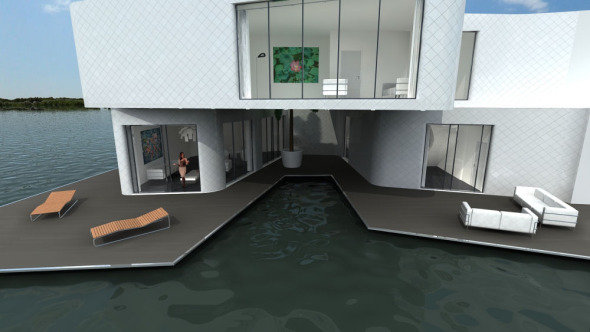

This is all well and good for the Dutch, but what about the flat, flood-prone coastal regions here in the USA? Like, for example, Florida? Well, the Dutch have thought of that. Another Waterstudio-Docklands project is Amillarah Floating Private Islands Miami, located in Maule Lake. A former limestone rock quarry, the privately owned lake is an inlet a mile and a half from the ocean, a bit north of Miami Beach.

Dubbed a “villa flotilla” by the Miami Herald, the complex will consist of 29 6,000-square-foot condos priced at $12.5 million each. As with Citadel and other Dutch Docklands projects, there are plans to boost the Maule Lake project’s sustainability, in this case with solar and hydrogen-powered generators.

Though similar to Citadel in the Netherlands, this project wouldn’t have been possible Stateside without a 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision that floating homes could be considered real estate, not boats. As the Herald explained, would-be buyers of Amillarah condos can get a mortgage and homeowners’ insurance, and the Coast Guard can’t bust in and inspect for life jackets.

Maule Lake will be out of reach for most Floridians financially, but if the ambitious project succeeds, it will provide visual evidence to Miami that floating houses can be done, and perhaps inspire larger, more modest developments like Amsterdam’s Waterbuurt.

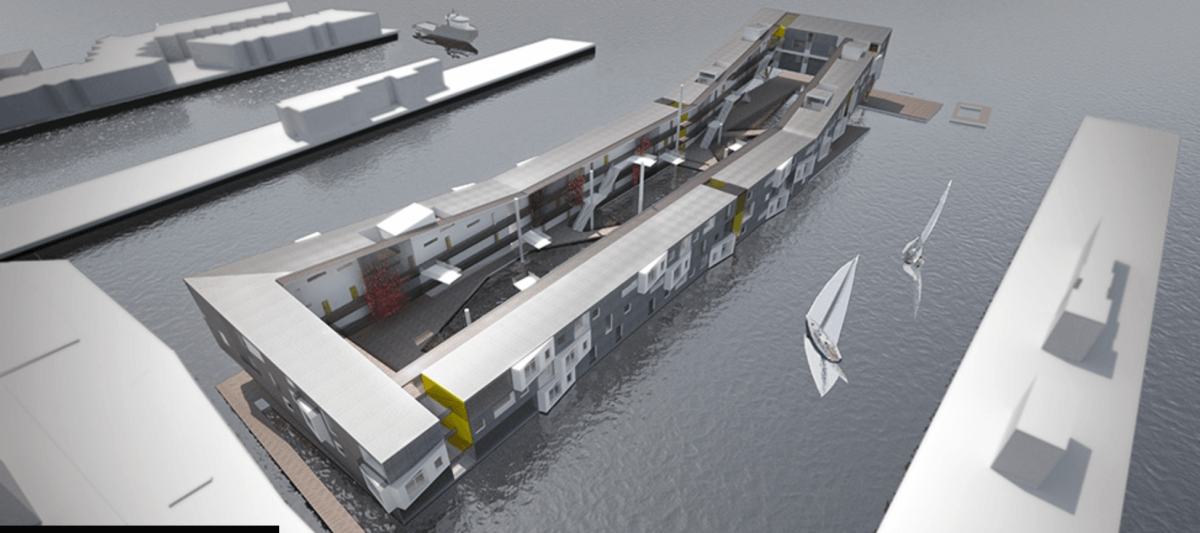

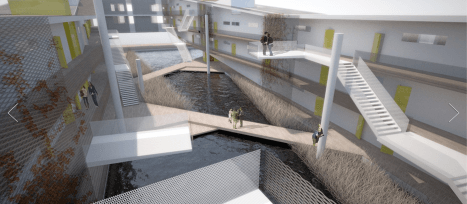

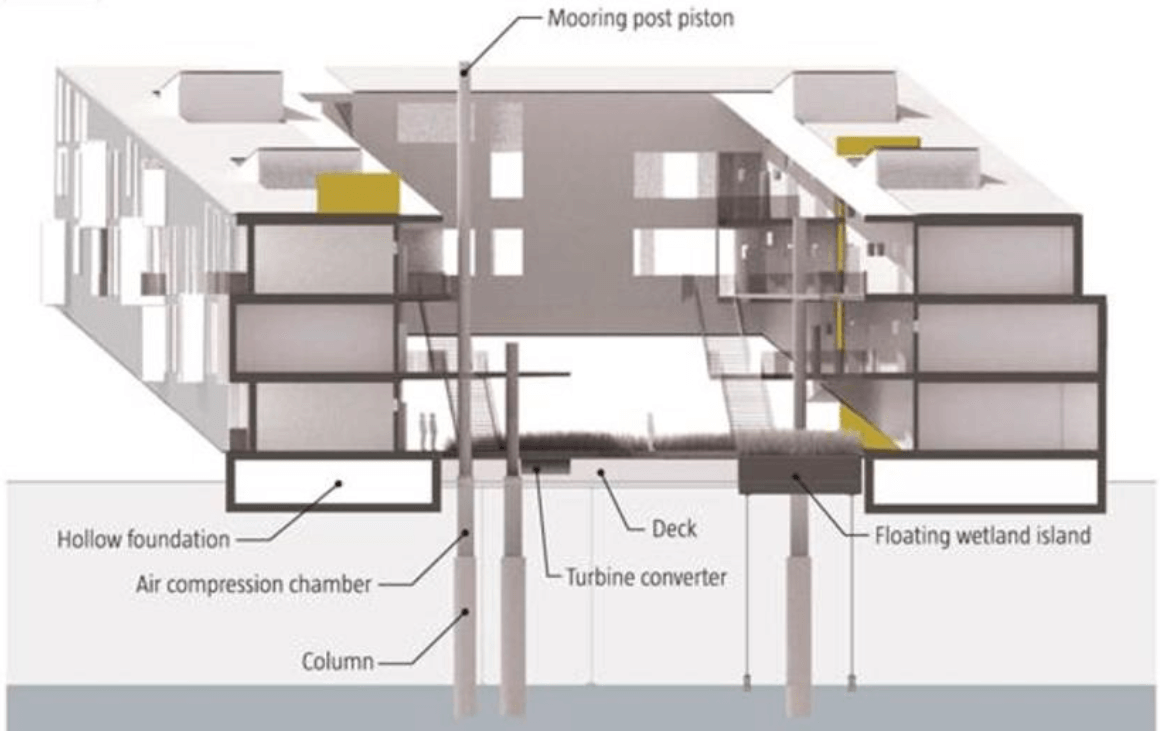

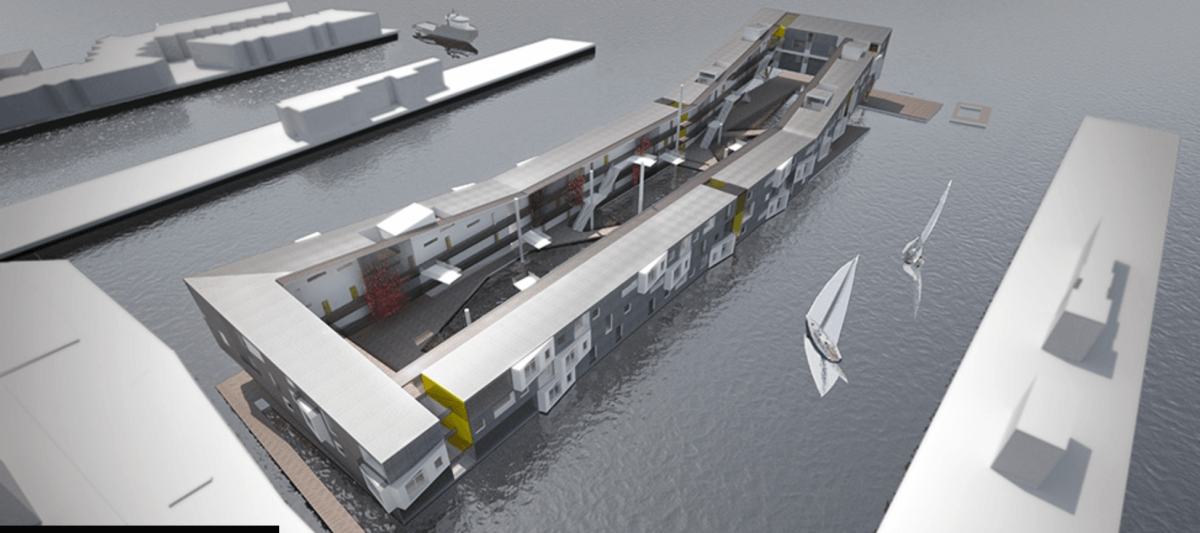

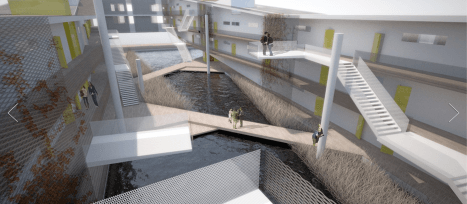

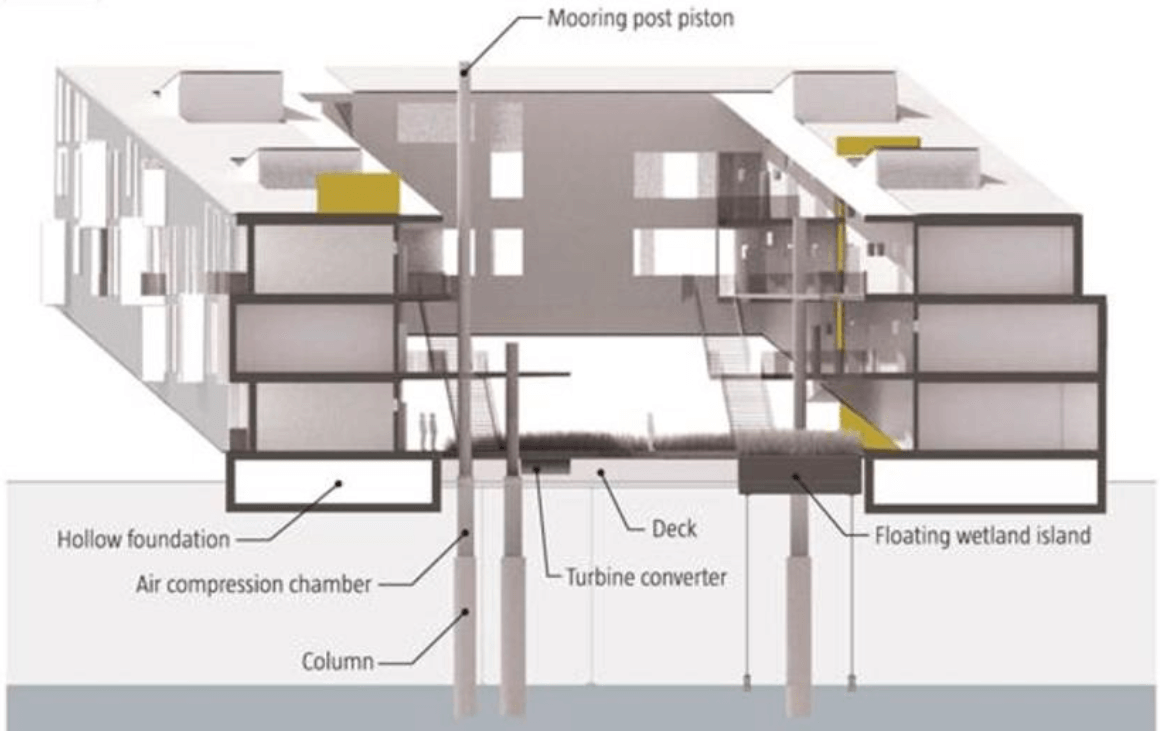

Renderings courtesy of architect Brian Healy

Not hidebound in the Hub

In Boston, architect Brian Healy, for the local office of Perkins+Will, won awards in 2013 for his design of Floatyard, a proposed apartment complex that would stretch out onto the Mystic River from the Charlestown Navy Yard, using much of the same technology as the abovementioned Dutch initiatives. Were Floatyard and similar projects to become reality here, Healy argues that they would not only help the city adapt to rising seas but also revitalize disused shipyards (for example, in East Boston and Quincy) and reorient Boston—historically a seaport—toward its natural center, the harbor.

What makes Floatyard unique is its central courtyard: a floating wetland island, built above the foundation, to be seeded with native marsh grass and aquatic wildlife. The design also includes a plan to harvest tidal energy via the structure’s mooring post pistons.

Elder statesman of architecture criticism Robert Campbell could have been talking about any of the above floating buildings when he wrote of Floatyard: “Like a lot of good ideas, this one is just crazy enough to make sense.” Given the prediction for the ocean to rise between three and five feet by the year 2100, it might be more crazy not to build on floating tubs.

Click here for the source website

Click here to view the article in pdf

Photo by Roos Aldershoff, courtesy of Marlies Rohmer Architects and Urbanists

Photo by Roos Aldershoff, courtesy of Marlies Rohmer Architects and Urbanists Photo by Marcel van der Berg

Photo by Marcel van der Berg

Hi Europe

Hi Europe