Weg afgesloten om woonarken naar Oranjewijk te takelen

By Omroep Flevoland

2019.Oct.24

Een spectaculair gezicht vrijdagochtend op de Urkerweg bij Urk. Daar worden zeven grote woonarken vanuit de Urkervaart de weg over getild om naar hun nieuwe plek in de Oranjewijk te gaan.

De eerste ark ging rond 8.30 uur het water over. De eigenaren en andere Urkers stonden toe te kijken.

De drijvende woningen zijn gemaakt door het Urker bedrijf ABC Arkenbouw en hebben ieder een eigen kleur. Om ze op hun eindplek te krijgen moesten drie bomen worden gekapt en is de weg tijdelijk dicht.

De voorbereidingen zijn donderdagmiddag al begonnen. Afgelopen nacht werden twee kranen opgebouwd.

Ecco le case galleggianti in cui vivremo quando salirà il livello del mare

By Enrico Maria Corno

compartilhando felicidade

2019.Oct.18

Se è vero che nel 2100 i’Adriatico si alzerà di 140 cm, molte saranno le zone sommerse dalle acque. E in Italia e all’estero si sviluppa il settore delle floating house

Il futuro (galleggiante) è adesso

In una recente intervista alla Bbc, l’architetto olandese Koen Olthuis, il guru dell’architettura galleggiante, ha citato uno studio secondo il quale il 78% delle grandi città nel mondo sono state edificate vicino al mare o comunque a grandi bacini d’acqua che ne influenzano la vita. «L’acqua è un’opportunità e l’architettura galleggiante è il prossimo step nell’evoluzione urbanistica delle città. Negli ultimi 15 anni abbiamo cercato di combattere la natura per cercare di sottometterla alle nostre esigenze mentre ora si comincia a pensare che è meglio assecondarla, soprattutto pensando al previsto innalzamento del livello delle acque dovuto allo scioglimento progressivo dei poli. In Olanda ci sono oltre 10.000 case galleggianti ma spesso sono solo ricavate da vecchi battelli. Gli edifici che oggi realizziamo con le tecnologie più avanzate sulla terraferma, domani verranno costruiti su piattaforme galleggianti».

Parte il Made in Italy

Ora anche in Italia il mercato immobiliare galleggiante sta muovendo i primi passi: se esistono già alcuni operatori turistici che hanno realizzato villaggi e resort galleggianti acquistando le houseboat all’estero – dalla Polonia alla Turchia – ora stanno cominciando ad apparire i primi costruttori che, pur producendo ancora a livello artigianale, propongono le prime case galleggianti Made in Italy.

Quanti tipi di floating house

Il mondo si divide in case galleggianti “fissate a terra”, che non hanno la capacità di muoversi autonomamente e che rispondono ai regolamenti comunali pagando gli oneri di urbanizzazione, e case galleggianti “a motore” che sono formalmente dei natanti e che, ad esempio, hanno l’obbligo di smaltire le acque nere senza collegarsi al sistema fognario. Oltre a queste due categorie, è rilevante anche la distinzione tra case galleggianti prodotte artigianalmente e case che escono da una catena di montaggio industriale; così come tra quelle che vengono progettate per essere domicilio stabile e continuativo (da qualche anno in Italia la legge permette di chiedere la residenza in un porto) e quelle destinate ad essere affittate solo per un periodo di vacanza estiva.

Tutto un altro mondo

Recuperare un vecchio battello, ormeggiarlo lungo un molo e ristrutturarlo in modo tale che possa ospitare una casa può essere scomodo, limitante e parecchio costoso. Spesso conviene costruire ex novo. In Italia – nonostante la presenza di centinaia di cantieri nautici (e di 7.500 km di coste) – non c’è ancora una realtà industriale che creda e investa nella realizzazione di case galleggianti ed è pur difficile trovare artigiani che possano vantare le necessarie competenze in ingegneria nautica e civile per creare un progetto certificabile dagli enti preposti. Questo è però il caso raro di Minimal, una sas tra Mantova a Verona che ha recentemente messo in acqua un ristorante da 200 metri quadri lungo l’Adige, una residenza abitativa su misura di due piani acquistata da una famiglia, che ha scelto di vivere nel porto turistico di Genova, e una serie di piccoli “camper galleggianti” di pochi mq, noleggiabili sul Canal Bianco in Polesine e guidabili senza patente.

Apriamo i porti sull’Adriatico

Quando pochi anni fa sono cambiate le leggi sulla nautica da diporto, molte barche di grandi dimensioni – soprattutto sull’Adriatico – hanno deciso di fare base nella molto più economica Croazia. C’è chi, di fronte ai porti italiani rimasti semivuoti, ha trovato una soluzione e li ha riconvertiti in villaggi di case galleggianti. È accaduto a Rimini, ad esempio, e a Lignano Sabbiadoro (che probabilmente è la località italiana con la maggior concentrazione di houseboat potendo vantare ben due diversi floating resort) alla foce del fiume Tagliamento.

Il modello chiavi in mano

Le houseboat scelte per la Marina di Rimini sono prodotte da una azienda slovena che da decenni opera nel settore di camper e caravan: un molo galleggiante lungo anche 25 metri dove viene installata una costruzione da 50 a 150 mq dotata di ogni comfort prodotta industrialmente. A corredo, ci sono due motori elettrici, una a poppa e uno a prua (smontabili quando non si intende muoversi) che permettono alla “chiatta” di spostarsi e le forniscono lo status di natante. Il valore aggiunto è dato però dal sistema di galleggiamento brevettato: 96 cubi di materiale plastico inaffondabile contengono un impianto innovativo per il riciclo e la depurazione delle acque nere, che permette alla houseboat di rimanere stabilmente in porto senza dover ricorrere costantemente allo spurgo o senza dover uscire per scaricare al largo.

Il modello chiavi in mano

Le houseboat scelte per la Marina di Rimini sono prodotte da una azienda slovena che da decenni opera nel settore di camper e caravan: un molo galleggiante lungo anche 25 metri dove viene installata una costruzione da 50 a 150 mq dotata di ogni comfort prodotta industrialmente. A corredo, ci sono due motori elettrici, una a poppa e uno a prua (smontabili quando non si intende muoversi) che permettono alla “chiatta” di spostarsi e le forniscono lo status di natante. Il valore aggiunto è dato però dal sistema di galleggiamento brevettato: 96 cubi di materiale plastico inaffondabile contengono un impianto innovativo per il riciclo e la depurazione delle acque nere, che permette alla houseboat di rimanere stabilmente in porto senza dover ricorrere costantemente allo spurgo o senza dover uscire per scaricare al largo.

Conheça Arkup, o Iate Casa de Luxo!

By Compartilhando Felicidade

2019.Oct.18

Já pensou em viver em uma casa flutuante? E se te dissermos que ela é de luxo e auto suficiente? Exatamente. A empresa Arkup, com sede em Miami, tirou do papel seu primeiro iate casa de luxo!

O projeto do “iate habitável” foi inicialmente apresentado durante o Fort Lauderdale International Boat Show em 2017. Ele é uma embarcação de 75 pés, retangular, ecológica, resistente a furacões, que parece um apartamento de luxo na água.

A Arkup é o resultado de vários anos de pesquisa, a contribuição de um dos principais designers holandeses de casas flutuantes e uma empresa de design de interiores francesa, bem como desenvolvimentos técnicos que ainda não haviam sido vistos na indústria de iates. A empresa também seguiu os padrões de construção ABYC e NMMA para garantir que ela seja construída como um barco, em vez de uma casa flutuante.

Sustentabilidade a bordo do iate casa

A primeira Arkup realmente parece um luxuoso apartamento à beira-mar. Possui paredes de vidro, vários níveis subdivididos em quartos e acesso instantâneo à água. As placas solares geram energia suficiente não apenas para luzes e ar condicionado, mas também para que seus motores elétricos de 272 hp, que fazem com que ele navegue a 7 nós com uma autonomia de 300 milhas náuticas. Ele pode ficar a até 20 milhas da costa, isso significa que os proprietários podem ficar em marinas ou piers locais.

Ela ainda conta com uma plataforma hidráulica que pode ser usada para mergulho ou para levantar facilmente um tender ou uma moto aquática.

O “iate casa” também tem quatro suportes hidráulicos que podem se fixar no solo em águas rasas e erguer o iate da água. Esse é um bom recurso para não ser atacado em tempestades ou para convidados que se sentem mal com o balanço da água. Ele também é projetado para suportar ventos de 155 km/h ou um furacão de categoria 4.

A primeira Arkup está em Miami e disponível para charters de longo e curto período, onde a luz do sol fornece energia durante todo o ano. O iate também coleta água da chuva, tornando-o totalmente auto-suficiente.

Is dit dé oplossing voor de krapte op de woningmarkt?

By Kop-Munt

2019.Oct.17

Traditionele projectontwikkelaars hanteren vaak het motto: meer woningen, minder groen. Maar dat is nergens voor nodig volgens architect Koen Olthuis. Want we kunnen snel én zonder milieuschade heel simpel steden uitbreiden op het water. En daarmee is een oplossing voor de krapte op de woningmarkt in zicht.

“Kun je wel duidelijk maken dat het hier niet gaat over plannen voor huizen aan het water met een steiger? Anders denkt de lezer misschien dat ik weer zo’n architect ben met een wild, maar onuitvoerbaar plan.” Koen Olthuis van Waterstudio.nl wil graag vertellen over de oplossingen die bouwen op het water kan bieden voor de krapte op de woningmarkt. “Waterwonen is eenvoudig te realiseren en de techniek is bewezen. Als de overheid en gemeenten nu ook meewerken kunnen we snel overgaan tot de uitvoering.”

Extra ruimte

Olthuis vergelijkt de huidige krapte op de woningmarkt met de situatie in steden zo’n 120 jaar geleden. Toen werden ook hele steden volgebouwd en uitgebreid om in de woonbehoefte te voorzien.

De stedelijke infrastructuur kwam daardoor flink onder druk te staan. “Tot meneer Otis de lift uitvond. Daardoor gingen ontwikkelaars en architecten anders denken en al snel werd hoogbouw gerealiseerd.” Die hoogte wordt in een aantal steden al goed benut, maar er is nog wel een onontgonnen gebied: het water. “Water biedt een prima oplossing voor stadsuitbreiding,” volgens Olthuis. “Zeker als je bedenkt dat 90 procent van de grootste steden ter wereld sowieso al aan het water ligt.”

Plug & Play

De technieken voor waterwonen zijn al lang voor handen. Denk bijvoorbeeld aan booreilanden, die al jaren worden gebouwd; een deel van die methoden worden ook gebruikt voor waterwonen.

“Tot een aantal jaar geleden was waterwonen vooral bestemd voor de happy few,” vertelt OIthuis. “Mooie villa’s in Miami, luxe eilanden in de Arabische Emiraten, het kan allemaal. Maar waterwonen kan ook echt een oplossing bieden voor de krapte op de woningmarkt in Nederland.”

Volgens Olthuis kunnen aannemers met een beetje hulp heel eenvoudig overgaan tot het bouwen van waterwoningen. “En die worden dus op een andere locatie gebouwd en vervolgens kant en klaar naar de woonlocatie gevaren. Ook de andere voorzieningen als wegen, winkels en groen kunnen zo worden gebouwd. Als je een geschikt stuk water hebt, bijvoorbeeld een oude haven, kun je zo in één keer een woonomgeving aanleggen die af is.

Gemeenten en milieu

Als het zo eenvoudig is, waarom worden dan nog niet overal waterwoningen gebouwd? “Mensen moeten nog wel even wennen aan deze mogelijkheden, net als destijds met de hoogbouw,” meent Olthuis. “Daarbij moeten gemeenten en overheden ook watergebieden toewijzen voor bewoning en de regelgeving daarop aanpassen.”

Over de milieuregelgeving hoeven gemeenten zich volgens Olthuis geen zorgen te maken. “We moeten de waterwoningen zo bouwen dat ze geen negatieve invloed hebben op het ecosysteem. Daarbij bouwen we het ook nog eens ‘scarless’. Dat betekent dat er geen sporen, laat staan schade, overblijven als de waterwoningen worden weggehaald.

Mogelijkheden voor hypotheken

Op waterwoningen kan ook een hypotheek worden afgesloten, maar het vergt wel dat er iets anders gedacht wordt. “De waterwoningen kunnen in principe worden aangemerkt als woning, of als boot, het is maar net wat een gemeente wil.”

De flexibele locatie van een waterwoning hoeft voor de hypotheek ook geen probleem te zijn volgens Olthuis.”Stel, je plaatst een drijvende woontoren midden in een stad, dan kan de gemeente een tijdelijke bestemming aanwijzen voor bijvoorbeeld 5 jaar. In de voorwaarden kan dan worden opgenomen dat de woning na 5 jaar tenminste naar een gelijkwaardige locatie wordt verplaatst. Daarmee zijn direct twee problemen opgelost: het risico is voor klant en geldverstrekker afgedekt, én een stad blijft flexibel in de ontwikkeling van de infrastructuur.”

The ‘blue economy’ is changing how we see the ocean. But with opportunity comes risk

By Antony Funell

ABC Australia

2019.Oct.11

Dutch marine architect Koen Olthuis has floated a novel idea. He wants to make the Olympics more affordable by staging them on water.

He predicts that would bring down the enormous infrastructure costs involved in staging the Games and allow poorer countries to bid for them.

The Olympics, he believes, needs to take on a bluer, not just a greener, tinge.

“You do it on water and you say, ‘We will build some floating stadiums and floating hotels and you can lease these structures for your city. And you use them and pay for their use for three or four months,’” Mr Olthuis says.

“Then they move to another city. It becomes much more logical.”

His vision might seem fanciful until you realise that the world’s largest ocean liner, Symphony of the Seas, already accommodates just under 7,000 passengers, and its length is the equivalent of almost four football fields.

So, engineering a floating hotel or stadium clearly isn’t a problem.

“In Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, we’ve already been active in designing these kinds of structures,” Mr Olthuis says.

“It’s more where do you place them, what kind of water you have, is it deep enough, what kind of flow is there, what kind of extreme weather you can expect.”

BECOMING LESS DEFENSIVE ABOUT THE OCEANS

The ocean-going Olympics is, for the moment, a thought experiment.

But it reflects a changing attitude among architects, engineers and urban designers.

Photo:

Koen Olthuis is one of the architects who “see water as an opportunity”. (Supplied: Waterstudio.NL)

“With improved technology we’ve found so many more ways that we can build into the sea,” says environmental scientist Katherine Dafforn.

That reassessment, she says, is being driven by the twin factors of climate change and urban congestion.

“We can’t easily remove those drivers, those stressors, so we do need to find a solution. And the oceans do offer some opportunities to find more space to house our population,” she explains.

Mr Olthuis believes the experience of the Netherlands can serve as an example of best practice.

The Dutch have traditionally viewed the sea as the enemy, he says, as a force to be conquered, but that’s now quickly changing.

Photo:

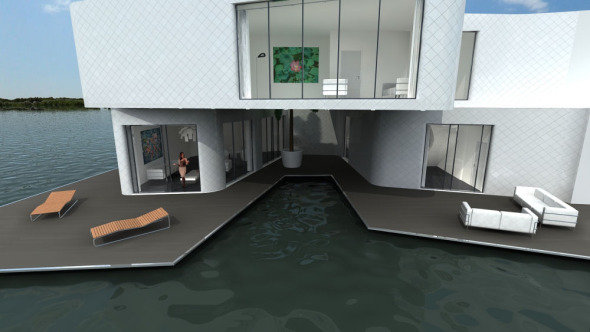

An artist’s impression of floating apartment buildings. Is this the housing of the future? (Supplied: Architect Koen Olthuis – Waterstudio.NL)

“We live in a country where we shouldn’t live — it’s all beneath sea level. And now with climate change and a higher sea level we see it’s more difficult to keep our country dry,” Mr Olthuis says.

“So, we’re rethinking that and saying, maybe in some parts of Holland we should just let water come in and then start building on top of the water.

“WE SEE WATER AS AN OPPORTUNITY.”

A BOOM IN OFFSHORE ACTIVITY

The Queensland University of Technology’s Brydon Wang says that attitudinal change is beginning to transform our near coastal environments, with a wide range of vital urban infrastructure now being located offshore, especially energy-related facilities.

The Hywind floating wind farm is a prime example. It commenced operation 24 kilometres off the coast of Scotland in 2017. Its five massive turbines are 250 metres tall and are tethered to the ocean floor using giant chains.

They’re purpose built for resilience — to work with nature, not against it.

Hywind is one of around 50 floating wind farms currently planned or under construction in Europe.

Late last year it proved its long-term viability by continuing to generate power during hurricane-like conditions.

Mr Wang says the “natural moat-like environment of the sea” offers protection to such facilities. And the fact that they float provides maximum flexibility.

“For example, if you put a desalination plant in the ocean, you might have a situation where there is drought in a particular city and you can float that desalination plant to where it is needed,” he says.

That philosophy also appears to underpin the controversial development of Russia’s first floating nuclear power station.

It took more than 10 years to construct and began its maiden voyage in August.

Its role, according to Russian authorities, will be to service remote mining operations in isolated areas above the Arctic circle.

Photo:

The floating power unit being towed to Atomflot moorage of the Russian northern port city of Murmansk. (Getty: Alexander Nemenov )

But this new focus on the oceans isn’t just about energy production or population expansion.

Mr Wang believes that by taking a “floating cities” approach, town planners can also enhance the cultural life of urban areas.

“One of the main problems with the way our coastal urbanisation has occurred is that we’ve got very flat and linear cities that are compressed against the coastlines, and that actually doesn’t make for very vibrant cities,” he says.

“If you look at Korea and Singapore they are starting to put immense cultural facilities in the water.

“Singapore has its massive floating stage that sits right in the marina. We’ve got a lot of cultural and exhibition spaces in Seoul that are floating in the nearby water bodies.”

FROM URBAN CONGESTION TO MARINE SPRAWL

Another way in which governments are choosing to deal with the twin difficulties of climate change and congested coastal cities is by “reclaiming” land from the sea.

Katherine Dafforn’s research, conducted with colleagues in Singapore, Italy and the US, suggests 450 artificial islands have been created in recent years to meet a whole range of needs — from military applications to tourism to airport construction.

Dr Dafforn also notes vast areas of the coastal marine environment have been walled off and filled in, with estimates that up to 25 per cent of Singapore is built on reclaimed land. For Tokyo it’s 20 per cent.

But China, she says, has been the most expansive.

“They’ve reclaimed extensive stretches of their inter-tidal zone. Around 13,000 square kilometres of their intertidal mudflats have been lost due to land reclamation,” Dr Dafforn says.

“I think that there is definitely a shift and more countries are actually investing money in doing it, even places like Monaco, places like the Maldives, all have their own plans for artificial islands.”

MORE STORIES FROM FUTURE TENSE:

But that trend, warns Dr Dafforn, risks creating “marine urban sprawl” every bit as damaging as its onshore equivalent.

“It needs to happen with some more sustainable ideas in mind,” she adds.

“The technology for building artificial islands has grown at the same time ecological understanding of the impacts and how to manage them has grown.”

She points to the Pacific where several artificial islands and structures have been created over coral reefs, resulting in enormous ecological harm.

“So, if we can put ecologists and engineers together at the beginning, when construction is first being planned and designed, then I think we have a lot of opportunities to build these artificial islands in a much more ecologically sustainable way,” she says.

Mr Olthuis believes architects and engineers need to embrace a double-sided approach to their design: thinking not just about what they build above the water, but also below it.

“For every project that we do we first have to do an environmental impact assessment. We measure the condition of the ecosystem before we do anything,” he says.

“We work with what we call blue habitats, these are structures that we connect to the underside of our buildings or our floating parks or whatever we do on water.

“And they have an effect on the water life — a habitat for fish, for green life under the structures.”

THE ‘BLUE ECONOMY’ — ENLIGHTENED OR EXPLOITATIVE?

The growth in interest in marine architecture and offshore engineering is now being described by the United Nations and others international organisations as the emerging “blue economy”.

An exact definition for what that term encompasses is hard to come by.

Even some of its proponents agree it’s a nebulous phrase which is being used to embrace everything from sustainable aquaculture to ocean-floor mining.

Darren Cundy from the newly-created Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre in Tasmania believes the label should only be used for activities with a sustainable edge.

His $329 million project is researching the development of a giant floating fish farm. One that can also generate enough electricity to be self-sufficient.

“What really is clear is that the blue economy is challenging us to realise that the sustainable management of ocean resources is going to require a collaboration across borders and across sectors through a whole range of partnerships on a scale that really we haven’t seen before,” Mr Cundy says.

“The oceans are a vast resource and there are different perspectives on how the economic value of that might be tackled.”

But Fauna and Flora International’s Daniel Steadman worries about the veracity of an approach that tries to marry the seemingly contradictory aims of promoting environmental responsibility while increasing opportunities for exploitation.

“WHAT I FIND PROBLEMATIC IS THAT THE WORLD DOESN’T NECESSARILY WORK LIKE THAT,” HE SAYS.

“If you take rare earth metals from the ocean claiming that it’s because you’ll take less from the land, and then both the new extraction in the ocean starts up and the old extraction on the land continues, you’ve perpetuated a problem, probably created a new one, and not solved anything.

“Similarly, if you farm fish to reduce the need to catch them in the ocean, but then the fish in your farm need to eat fish from the ocean, you’ve created this sort of negative feedback loop of interdependencies where neither people nor the ocean are improving.”

The one thing that is certain is that as the world’s population increases exponentially — and as food, resources and space become a premium — more and more interest will be directed toward ocean resources, for better or worse.

Oceania – The ‘blue economy’ is changing how we see the ocean. But with opportunity comes risk

By Central da Pauta

2019.Oct.11

Dutch marine architect Koen Olthuis has floated a novel idea. He wants to make the Olympics more affordable by staging them on water.

He predicts that would bring down the enormous infrastructure costs involved in staging the Games and allow poorer countries to bid for them.

The Olympics, he believes, needs to take on a bluer, not just a greener, tinge.

“You do it on water and you say, ‘We will build some floating stadiums and floating hotels and you can lease these structures for your city. And you use them and pay for their use for three or four months,’” Mr Olthuis says.

“Then they move to another city. It becomes much more logical.”

His vision might seem fanciful until you realise that the world’s largest ocean liner, Symphony of the Seas, already accommodates just under 7,000 passengers, and its length is the equivalent of almost four football fields.

So, engineering a floating hotel or stadium clearly isn’t a problem.

“In Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, we’ve already been active in designing these kinds of structures,” Mr Olthuis says.

“It’s more where do you place them, what kind of water you have, is it deep enough, what kind of flow is there, what kind of extreme weather you can expect.”

BECOMING LESS DEFENSIVE ABOUT THE OCEANS

The ocean-going Olympics is, for the moment, a thought experiment.

But it reflects a changing attitude among architects, engineers and urban designers.

Photo:

Koen Olthuis is one of the architects who “see water as an opportunity”. (Supplied: Waterstudio.NL)

“With improved technology we’ve found so many more ways that we can build into the sea,” says environmental scientist Katherine Dafforn.

That reassessment, she says, is being driven by the twin factors of climate change and urban congestion.

“We can’t easily remove those drivers, those stressors, so we do need to find a solution. And the oceans do offer some opportunities to find more space to house our population,” she explains.

Mr Olthuis believes the experience of the Netherlands can serve as an example of best practice.

The Dutch have traditionally viewed the sea as the enemy, he says, as a force to be conquered, but that’s now quickly changing.

Photo:

An artist’s impression of floating apartment buildings. Is this the housing of the future? (Supplied: Architect Koen Olthuis – Waterstudio.NL)

“We live in a country where we shouldn’t live — it’s all beneath sea level. And now with climate change and a higher sea level we see it’s more difficult to keep our country dry,” Mr Olthuis says.

“So, we’re rethinking that and saying, maybe in some parts of Holland we should just let water come in and then start building on top of the water.

“WE SEE WATER AS AN OPPORTUNITY.”

A BOOM IN OFFSHORE ACTIVITY

The Queensland University of Technology’s Brydon Wang says that attitudinal change is beginning to transform our near coastal environments, with a wide range of vital urban infrastructure now being located offshore, especially energy-related facilities.

The Hywind floating wind farm is a prime example. It commenced operation 24 kilometres off the coast of Scotland in 2017. Its five massive turbines are 250 metres tall and are tethered to the ocean floor using giant chains.

They’re purpose built for resilience — to work with nature, not against it.

Hywind is one of around 50 floating wind farms currently planned or under construction in Europe.

Late last year it proved its long-term viability by continuing to generate power during hurricane-like conditions.

Mr Wang says the “natural moat-like environment of the sea” offers protection to such facilities. And the fact that they float provides maximum flexibility.

“For example, if you put a desalination plant in the ocean, you might have a situation where there is drought in a particular city and you can float that desalination plant to where it is needed,” he says.

That philosophy also appears to underpin the controversial development of Russia’s first floating nuclear power station.

It took more than 10 years to construct and began its maiden voyage in August.

Its role, according to Russian authorities, will be to service remote mining operations in isolated areas above the Arctic circle.

Photo:

The floating power unit being towed to Atomflot moorage of the Russian northern port city of Murmansk. (Getty: Alexander Nemenov )

But this new focus on the oceans isn’t just about energy production or population expansion.

Mr Wang believes that by taking a “floating cities” approach, town planners can also enhance the cultural life of urban areas.

“One of the main problems with the way our coastal urbanisation has occurred is that we’ve got very flat and linear cities that are compressed against the coastlines, and that actually doesn’t make for very vibrant cities,” he says.

“If you look at Korea and Singapore they are starting to put immense cultural facilities in the water.

“Singapore has its massive floating stage that sits right in the marina. We’ve got a lot of cultural and exhibition spaces in Seoul that are floating in the nearby water bodies.”

FROM URBAN CONGESTION TO MARINE SPRAWL

Another way in which governments are choosing to deal with the twin difficulties of climate change and congested coastal cities is by “reclaiming” land from the sea.

Katherine Dafforn’s research, conducted with colleagues in Singapore, Italy and the US, suggests 450 artificial islands have been created in recent years to meet a whole range of needs — from military applications to tourism to airport construction.

Dr Dafforn also notes vast areas of the coastal marine environment have been walled off and filled in, with estimates that up to 25 per cent of Singapore is built on reclaimed land. For Tokyo it’s 20 per cent.

But China, she says, has been the most expansive.

“They’ve reclaimed extensive stretches of their inter-tidal zone. Around 13,000 square kilometres of their intertidal mudflats have been lost due to land reclamation,” Dr Dafforn says.

“I think that there is definitely a shift and more countries are actually investing money in doing it, even places like Monaco, places like the Maldives, all have their own plans for artificial islands.”

MORE STORIES FROM FUTURE TENSE:

But that trend, warns Dr Dafforn, risks creating “marine urban sprawl” every bit as damaging as its onshore equivalent.

“It needs to happen with some more sustainable ideas in mind,” she adds.

“The technology for building artificial islands has grown at the same time ecological understanding of the impacts and how to manage them has grown.”

She points to the Pacific where several artificial islands and structures have been created over coral reefs, resulting in enormous ecological harm.

“So, if we can put ecologists and engineers together at the beginning, when construction is first being planned and designed, then I think we have a lot of opportunities to build these artificial islands in a much more ecologically sustainable way,” she says.

Mr Olthuis believes architects and engineers need to embrace a double-sided approach to their design: thinking not just about what they build above the water, but also below it.

“For every project that we do we first have to do an environmental impact assessment. We measure the condition of the ecosystem before we do anything,” he says.

“We work with what we call blue habitats, these are structures that we connect to the underside of our buildings or our floating parks or whatever we do on water.

“And they have an effect on the water life — a habitat for fish, for green life under the structures.”

THE ‘BLUE ECONOMY’ — ENLIGHTENED OR EXPLOITATIVE?

The growth in interest in marine architecture and offshore engineering is now being described by the United Nations and others international organisations as the emerging “blue economy”.

An exact definition for what that term encompasses is hard to come by.

Even some of its proponents agree it’s a nebulous phrase which is being used to embrace everything from sustainable aquaculture to ocean-floor mining.

Darren Cundy from the newly-created Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre in Tasmania believes the label should only be used for activities with a sustainable edge.

His $329 million project is researching the development of a giant floating fish farm. One that can also generate enough electricity to be self-sufficient.

“What really is clear is that the blue economy is challenging us to realise that the sustainable management of ocean resources is going to require a collaboration across borders and across sectors through a whole range of partnerships on a scale that really we haven’t seen before,” Mr Cundy says.

“The oceans are a vast resource and there are different perspectives on how the economic value of that might be tackled.”

But Fauna and Flora International’s Daniel Steadman worries about the veracity of an approach that tries to marry the seemingly contradictory aims of promoting environmental responsibility while increasing opportunities for exploitation.

“WHAT I FIND PROBLEMATIC IS THAT THE WORLD DOESN’T NECESSARILY WORK LIKE THAT,” HE SAYS.

“If you take rare earth metals from the ocean claiming that it’s because you’ll take less from the land, and then both the new extraction in the ocean starts up and the old extraction on the land continues, you’ve perpetuated a problem, probably created a new one, and not solved anything.

“Similarly, if you farm fish to reduce the need to catch them in the ocean, but then the fish in your farm need to eat fish from the ocean, you’ve created this sort of negative feedback loop of interdependencies where neither people nor the ocean are improving.”

The one thing that is certain is that as the world’s population increases exponentially — and as food, resources and space become a premium — more and more interest will be directed toward ocean resources, for better or worse.

Parthenon Seawall Concept – The Under Energy Harvester

By Sarang Sheth

Yanko Design

Nexpected

2019.March.12

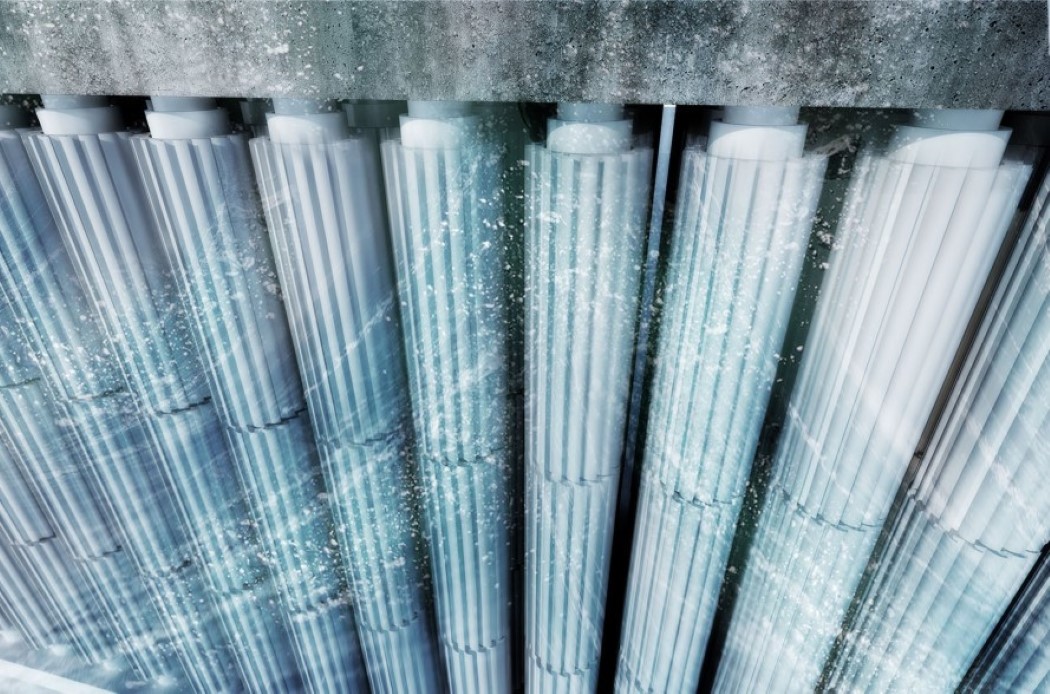

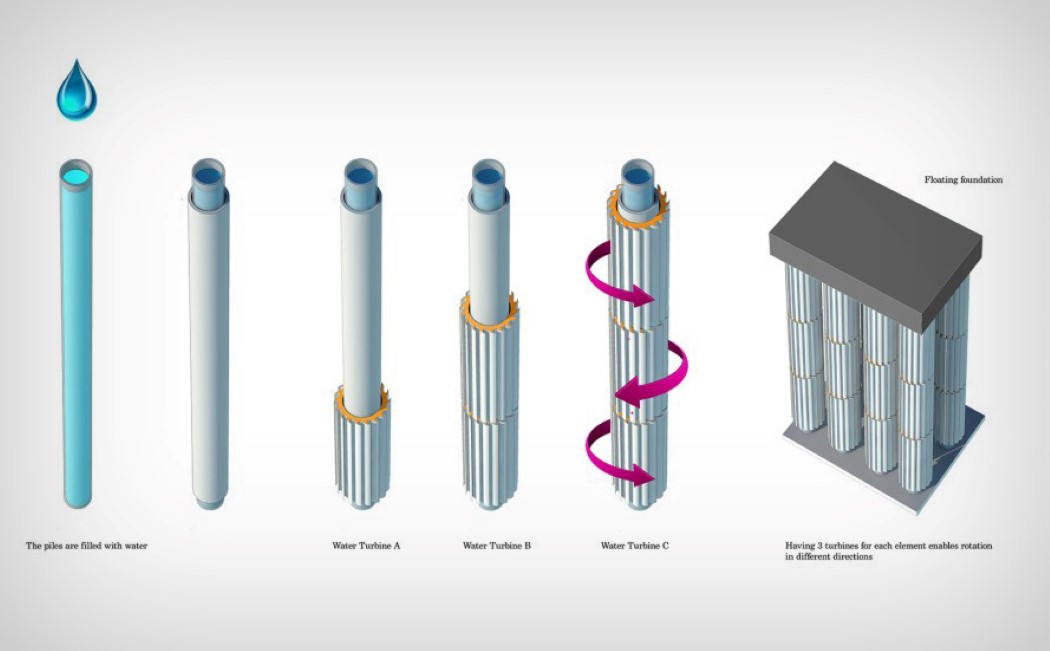

Neither have we discovered Atlantis nor has the Parthenon sunk yet! This is the Parthenon Seawall, a structure designed by Waterstudio led by Netherlands based Architect Koen Olthius, inspired by classical Greek architecture.

Designed to resemble the iconic temple of Athena, the Parthenon Seawall was created to harness tidal energy, turning water current into usable current (get it?)! It employs the familiar stacked pyramid structure with each pyramid being made to house three turbines (that rotate in alternate directions). The flow of water turns the turbines, and the energy generated is stored in its upper concrete platform.

It’s alternate rotating pattern also helps it do something rather important. The Parthenon Seawall can also break currents, preventing large waves and tides from damaging coastlines. The alternate rotations disrupt the water flow, becoming a protective barrier against damage caused to vulnerable coastlines, harbors, or riverbanks.

The Parthenon Seawall can be placed along coastlines to not only protect them but also harness energy in the process. Its upper surface can be used as a riverfront too, creating a space for greenery, and even human recreation! Ticks all the boxes, doesn’t it?!

Citadel, una urbanización flotante / Koen Olthuis y Waterstudio

By arq.com.mx

2019.Sept.21

A lo largo de los últimos años, los arquitectos han experimentado con soluciones poco convencionales, Koen Olthuis del despacho Water Studio es uno de ellos.

El trabajo de este arquitecto de origen holandés, por una parte, está orientado a la búsqueda de soluciones bioclimáticas y por otra, a los espacios arquitectónicos flotantes.

Citadel es uno de sus proyectos más recientes, que igual que los anteriores, destaca por sus innovadora y atrevida propuesta. El proyecto, que se ubicará en la ciudad holandesa de Westland, plantea una urbanización sobre el agua, que antes que luchar con el agua -que para los holandeses, año con año, resulta problemática- la aprovecha como una plataforma de desplante.

Este conjunto habitacional se localizará en la zona de New Water, un lugar que durante años fue desecado artificialmente y que ahora se va a llenar de nuevo con agua.

El proyecto, que será el primer conjunto de departamentos flotantes de toda Europa, estará conformado por 60 lujosas unidades habitacionales, compuestas por 180 piezas modulares dispuestas alrededor de un patio central.

La plataforma de soporte del conjunto consiste en un cajón de concreto de estructura ligera para que no se sienta ningún movimiento.

Could you live in a floating neighbourhood?

By Better World Solutions

Koen Olthuis is the founder of the Dutch architectural firm Dutch Docklands, that specializes in floating structures to counter concerns and impact of floods due to climate change and rising sea levels.

Climate change and rising river/coast levels: forget houseboats, try floating communities. The newest trend in real estate: building a home on top the water.

Floating communities

During his UP presentation — A Sustainable Future on the Waterfront — Koen shared his vision for literally building entire communities — and cities — that float! He studied architecture and industrial design at the Delft University of Technology, and has a patent on the methodology for producing a “floating base.”

Olthuis

In 2007, Koen was listed as one of “the most influential people in the world” in a readers’ poll by TIME magazine due to the worldwide interest in water developments. The French magazine Terra Eco chose him as one of the “100 green persons that will change the world” in 2011.

Do you want more information or get inspired from different floating city concepts, check the sidebar on the right.