En óf hij gedreven is. “Anders houd je het niet twintig jaar vol.” Architect Koen Olthuis zit in zijn kantoor in Rijswijk aan een kleurige glazen tafel voor een stapeltje lege A4’tjes en een pen, die hij tijdens het gesprek veelvuldig zal gebruiken om zijn woorden kracht bij te zetten. Hij doet al tien jaar niets anders dan drijvend bouwen, zegt hij. Al wil hij het zo eigenlijk niet noemen. “Het woord drijvend komt mijn strot uit.”

Hij wil dat woningen op water onderdeel worden van de normale stedenbouw. Net als hoogbouw ooit een keuze was om ruimte goed te gebruiken. Als je havens en polders gaat benutten als woonwijken, gebruik je de ruimte beter.

Olthuis wil af van de “freak architecture”. Van de “watervillaatjes met een bootje aan het water” voor de happy few. “Want dan blijft het altijd een nichemarkt.” Wonen op het water moet ook toegankelijk worden voor gewone mensen, vindt hij.

Duizenden polders

Aan de techniek ligt het niet. “In Nederland bouwen we meestal op palen of op staal. Kijk eens onder het Paleis op de Dam. Dertienduizend houten palen. Dertienduizend palen staan daar onder één gebouwtje! Dat slaat helemaal nergens op. Houten palen. Het hoogste bos van Nederland. Dat soort funderingen vinden wij fantastisch. Maar daarvan zeg je toch ook niet dat het om paalwoningen gaat?”

Wat hem betreft moeten polders in Nederland gebruikt worden om de woningnood aan te pakken. Laat maar onderlopen. Het land schreeuwt om locaties. Pak een deel van de Haarlemmermeerpolder. Of pak ergens een hele polder.

“We hebben 3.500 polders. Veenpolders. Droogmakerijen. Zeepolders. We halen het water eruit. Maar het is een kunstmatig systeem. Wij wonen met elkaar in een poldermachine. En die machine moet je onderhouden en droog houden. Anders kan je niet wonen en geen landbouw bedrijven. Maar er komt steeds meer regen en meer wateroverlast. Dus moet je harder pompen. Op lange termijn is dat systeem gewoon niet vol te houden.” Waarom al die polders droogmalen? Met verzilting langs de kust en CO2-uitstoot bij de veenpolders tot gevolg. Waar zijn we mee bezig, vraagt Olthuis zich af.

Klimaatverandering

Olthuis zet een kleine maquette op tafel van een drijvende wijk die op de Malediven gepland is. Daar wil de overheid vijftienduizend woningen op het water bouwen. De straten komen te staan op grote pontons en worden via knooppunten aan elkaar gekoppeld. Op een A4’tje tekent de architect een netwerk van lijntjes uit. Hij pakt zijn laptop erbij om nog een schets van bovenaf te laten zien. Het lijkt op een bloemkoolwijk, maar dan met water in plaats van tuinen.

De ontwikkeling van de drijvende stad op de Malediven zit sinds vorig jaar in een stroomversnelling. De plaatselijke minister van Milieu, Klimaatverandering en Technologie, Shauna Aminath, brak bij nieuwsmedium Bloomberg een lans voor de bouw van drijvende wijken. “Door de snelheid waarmee klimaatverandering toeneemt en de zeespiegel stijgt, moeten we op een hogere ondergrond gaan bouwen”, zei ze.

Olthuis vindt het “fantastisch” dat hij betrokken is bij het “opstarten van de nieuwe economie”. “Steun van de overheid is voor ons zó belangrijk”, zegt hij. Met “ons” doelt Olthuis op zijn architectenbureau Waterstudio.NL, ontwikkelaar Dutch Docklands Maldives én op de joint venture tussen de overheid en de Nederlandse onderneming: Dutch Docklands International. Bij het project zijn ook Nederlandse waterbouwers en een ingenieursbureau betrokken. Olthuis is de chief creative officer.

Het wordt een “miljardenproject”, volgens de architect. Critici vrezen dat de woningen door deze hoge kosten alleen te betalen zullen zijn door de rijken. Olthuis houdt de moed erin en denkt dat er in de drijvende stad straks ook plek is voor burgers met een meer bescheiden inkomen.

Onderwatertech

De drijvende stad komt in een lagune, waar de strandjes steeds verder zinken en het rif en het koraal heel dichtbij zijn. “Zo’n stad kan je niet bouwen in het midden van de oceaan, maar je kunt hem wel bouwen in de nabijheid van bestaande infrastructuur”, zegt Olthuis. Bijvoorbeeld dicht bij de hoofdstad Malé, die uit zijn jasje barst.

De woningen zijn fel gekleurd en krijgen onverharde (zand)straten, passend bij de lokale cultuur. “Maar onderwater is alles gewoon hightech”, verzekert Olthuis. Daar liggen het riool en alle leidingen.

De eerste drijvende woonwijk bestaat uit zeshonderd woningen (vier hoog met dakterras). De drijvende stad wordt over het water aangevoerd. Volgend voorjaar komen draagschepen met daarop straten: dat zijn stalen pontons van honderd bij dertig meter. De straten worden vastgemaakt aan palen, laat Olthuis zien met een paar pennenstreken op een A4’tje. “Het is eigenlijk een grote haven. Dat is niet wat mensen willen horen. Maar zo werkt zo’n stad wel.”

Drijvende flexwoningen

De woningen en straten komen uit China, India en Sri Lanka, landen die ook bij het project betrokken zijn. De woningen die ze maken zijn volgens Olthuis twee keer zo goedkoop als in Nederland, omdat arbeid veel goedkoper is. De flexibele steden van Olthuis kunnen zich aanpassen aan het seizoen. Tennisbanen kunnen na de zomer afdrijven en vervangen worden door parken. “Seizoensgebonden architectuur”, noemt Olthuis dat.

In zekere zin lijkt het op de flexwoningen die de laatste jaren in Nederland aanslaan. Die zijn ook verplaatsbaar. Olthuis: “Dat soort woningen juichen we alleen maar toe.” Ook flexwoningen komen in principe op tijdelijke bestemmingen. En wat hem betreft mogen ze ook drijven.

Olthuis zou graag zien dat het Rijk lege delen van havens in Nederland aanwijst om met drijvende wijken te starten. In Amsterdam of Rotterdam. Op het IJmeer of op de plek waar ooit de Markerwaard zou komen. Maar de architect ziet dat niet snel gebeuren, vanwege de huidige bestemming van die gebieden en verwachte bezwaren van natuurbeschermingsorganisaties. De duizenden polders in Nederland zijn kansrijkere locaties. “We moeten als land kijken of het economisch beter is om een aantal van die polders onder water te zetten.”

City-dokter

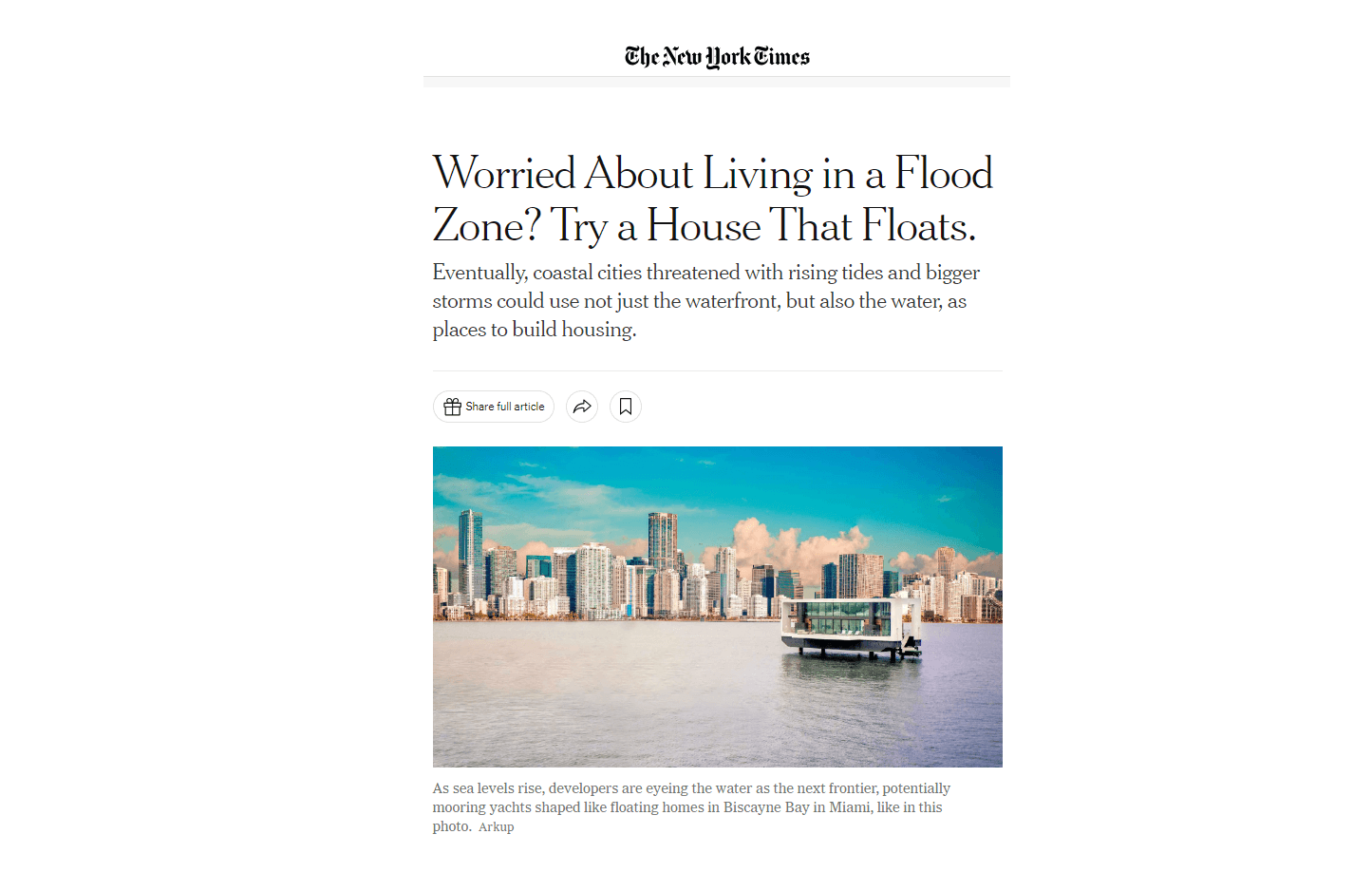

De woningnood vormt dé gelegenheid om aan de slag te gaan met drijvende wijken, vindt Olthuis. Anders blijft Nederland hangen in experimenten, zoals die met drijvende woningen bij IJburg in Amsterdam en een projectje in Rotterdam. In het buitenland wordt het concept serieuzer opgepakt, valt Olthuis op. Dat merkt hij alleen al aan de telefoontjes van buitenlandse media. “Vanmiddag word ik gebeld door The New York Times. Elke maand staat er wel een filmploeg hier.” Een week voor dit gesprek was Olthuis keynotespeaker op een congres over drijvend bouwen in Tokio.

Dat het concept van woningbouw op het water in Nederland tot nu toe niet echt aansloeg, frustreert hem. Het bewoog hem er jaren geleden toe aan de TU Delft te promoveren op het onderwerp. Om serieuzer genomen te worden in de stedenbouwwereld. Ook wilde hij de wereld van zijn moeder en vader bij elkaar brengen. “Aan mijn moeders kant zaten de scheepsbouwers. Aan vaders kant de art-nouveau-architecten.”

In plaats van architect zou hij zichzelf liever city-dokter willen noemen. Met water als medicijn. “Ik zie water als mogelijkheid om de stad te verbeteren.”

Tipping point

Inmiddels begint er beweging in te komen. “We gaan richting een tipping point waarin waterwonen, bouwen op natte ondergronden, als een volwaardig alternatief wordt gezien”, denkt Olthuis. Pensioenbeheerders meldden zich al met belangstelling. Ze willen verkennen of wonen op het water op grotere schaal een oplossing kan zijn. “De rol van architecten is om te laten zien dat je geld kan verdienen aan water. Dan volgen de ontwikkelaars wel”, is zijn overtuiging.

Nu Olthuis een doctorstitel heeft, lesgeeft aan de TU Delft en ziet hoe enthousiast studenten zijn over waterwonen, is zijn ambitie groter dan ooit. Hij hoopt dat hij uiteindelijk de stedenbouw kan verrijken.

Daar is dan wel steun van de overheid voor nodig. Die moet regels opstellen, vindt de architect. “Bijvoorbeeld: alles wat we gaan bouwen, moet verschoven kunnen worden. Zonder heel specifiek te zeggen dat het een waterwoning moet zijn. Dan gaat de industrie zoeken naar oplossingen en kunnen er mooie dingen gebeuren.”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/SUUS3GUP7RGN7HLZQWHC4SBRCM.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/XEZURS55LNALTHMKE2R7PT2ZLA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/SAEC42OEGFCSFGC7II35ZYJQAE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/5UWYJNB5LJFBPLSGIZ2V72FLOE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/HHCCCXL64RHEDCQC7FLCOP3YV4.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/D55AUUZXJXKPG53RCORZLRDROA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/DR3DFXEWCBE73LB3PNJSHC4WFM.webp)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/IYYB2WDAPVGZBOX7DT4X22P3Q4.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/DYJ27NLJXZFM3B5AZD72WQOTKQ.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/ZH5NQKA53BCZVFTBDJ25Z2TNIM.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/MJZWXQ3NOFHNXERTMCQKZ36MCQ.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/MAMDK5GD2ZAUVFWR7ZPHZ2VM6Y.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/KZL63RWVORHGXGR54ARROKUIJY.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/MIATBAFS2JFLZJEF3NVZKOSR5Q.jpg)