By Maarten Keulemans

Volkskrant

Loopt het wel zo mis met het klimaat als het lijkt? Wetenschapsredacteur Maarten Keulemans blikt terug vanuit het jaar 2069 – en ontdekt iets vreemds.

Het is achteraf misschien moeilijk voor te stellen, maar rond 2020 dachten veel mensen dat de wereld zou vergaan. Nieuwssites stonden vol onheilspellende berichten over het veranderende klimaat, in de boekwinkels lagen boeken met titels als Onze onbewoonbare planeet en op straat demonstreerden zelfs de schoolkinderen, met oogluikende toestemming van veel ouders en scholen.

Begrijpelijk ook wel. Vanaf ongeveer 1975 begonnen de broeikasgassen die de mens al sinds de 19de eeuw uitstoot steeds duidelijker door te werken in het systeem aarde. Plots trok de wereldtemperatuur aan, naar één volle graad warmer rond 2020. En overal begon men de gevolgen te merken. Smeltende ijsmassa’s aan de randen van Antarctica en Groenland, een vervaarlijk krimpende noordelijke poolkap – de noordelijke ijszee had in die dagen nog permanent ijs – en in de meer zuidelijke streken hittegolven, orkanen en bosbranden. Nog even, en ‘grote delen van de planeet raken onleefbaar’, zoals een in die dagen populaire activiste genaamd Marjan Minnesma stelde.

Intussen liep het klimaatbeleid vast. Waar het de internationale gemeenschap in de jaren tachtig van de vorige eeuw nog tamelijk soepel was gelukt ozonlaag afbrekende drijfgassen uit te bannen, bleek het tegengaan van broeikasgassen een paar bruggen te ver. ‘Bakken geld hebben we geïnvesteerd, maar de werkelijkheid is dat de CO2-uitstoot onverminderd voortgaat’, verzuchtte Oxford-hoogleraar Dieter Helm in 2018, ruim een kwart eeuw na het klimaatakkoord van Rio de Janeiro, ’s werelds eerste internationale klimaatverdrag.

Eind 2015 was er een sprankje hoop, toen 197 landen in Parijs in een allang weer vergeten klimaatakkoord beloofden de opwarming te beperken tot anderhalve graad, en echt, echt, écht onder de 2 graden te blijven. Maar binnen enkele jaren was die belofte alweer verwaterd. Haast geen land slaagde erin de uitstoot genoeg te matigen, in grote landen als Brazilië en de toenmalige Verenigde Staten kwamen leiders aan de macht die uit de afspraken stapten, en naties als China en India klaagden dat het Westen de miljarden aan klimaatsteun die het in Parijs had toegezegd maar niet leverde.

In Nederland gingen aanvankelijk nog stemmen op om voorop te lopen in het tegengaan van CO2. Totdat het kabinet Dijkhoff-I, onder druk van coalitiepartner Thierry Baudet, besloot de klimaatmaatregelen af te zwakken. ‘Het is niet mijn akkoord, ik ga het niet letterlijk uitvoeren’, had Dijkhoff begin 2019 al gezegd.

Zo betraden we de jaren 2020 in zak en as, terwijl de CO2-uitstoot maar bleef stijgen en de wereldtemperatuur record na record boekte. Op uw interface kunt u de filmpjes terugzien van wat er in dat decennium zoal gebeurde: de superhittegolven van 2023 en 2025, orkaan Nigel die Charleston verwoestte, orkaan Gavin die over het Witte Huis trok en natuurlijk de vele hittedoden tijdens de bedevaart in Mekka in 2027.

‘Het is, ik beloof het, erger dan je denkt’, schreef milieujournalist David Wallace-Wells in een essay dat in die dagen als een lopend vuurtje rondging over het datanet. ‘Als je ongerustheid over de opwarming van de aarde zich nog beperkt tot angst voor zeespiegelstijging, heb je niet half een idee van de verschrikkingen die mogelijk zijn.’

Terwijl wie goed luisterde, ook een ander geluid kon horen. ‘Over de gehele linie verloopt de energietransitie fantastisch en in voortdurende versnelling’, zei milieuwetenschapper Amory Lovins van het Rocky Mountain Institute opgetogen in een interview. Dat was nota bene in 2018, midden in de eerste ambtstermijn van president Donald Trump de Eerste.

Groene omslag

Zo waren er de micro-initiatieven.

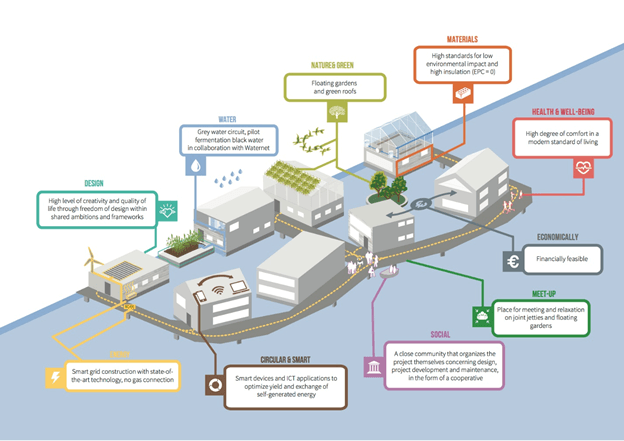

Al ruim vóór 2020 begonnen steeds meer steden, provincies, bedrijven en regio’s hun eigen klimaatbeloften in te dienen, op informeel ingerichte websites zoals de Non-state actor zone for climate action (NAZCA) van de VN, de Under2 Coalition voor regio’s, het Global Covenant of Mayors voor stadsbesturen en de Carbon Neutrality Coalition voor landen. Toen de internationale klimaatafspraken instortten, waren het deze kleintjes die overbleven, met al hun plannen voor auto-arme binnensteden, zuinige straatlampen, innovatieve riolen, groene daken en duurzame bedrijfspanden.

En dat maakte uit. Ouderen herinneren zich misschien nog de spontane straatfeesten die uitbraken toen Utrecht als eerste grote Nederlandse stad klimaatneutraal werd, amper een week later gevolgd door Gelderland als eerste klimaatneutrale provincie. Of neem Donald Trump I, die in 2020 uit de internationale klimaatafspraken stapte. Achter zijn rug om ging de groene omslag gewoon door: staten als Californië, Connecticut en New Jersey deden hun eigen klimaatbeloften, in Indiana en Colorado besloten energiebedrijven uit eigener beweging kolencentrales vervroegd te sluiten en te vervangen door duizenden megawatt aan wind- en zonne-energie, en multinationals als Facebook en Pepsi namen maatregelen om geen molecuul broeikasgas meer aan de dampkring toe te voegen. In Californië riep toenmalig gouverneur Jerry Brown in 2018 zelfs doodleuk een eigen klimaattop bijeen: een soort inzamelingsactie, waar bedrijven en plaatselijke besturen publiekelijk hun klimaatbeloftes kwamen verkondigen.

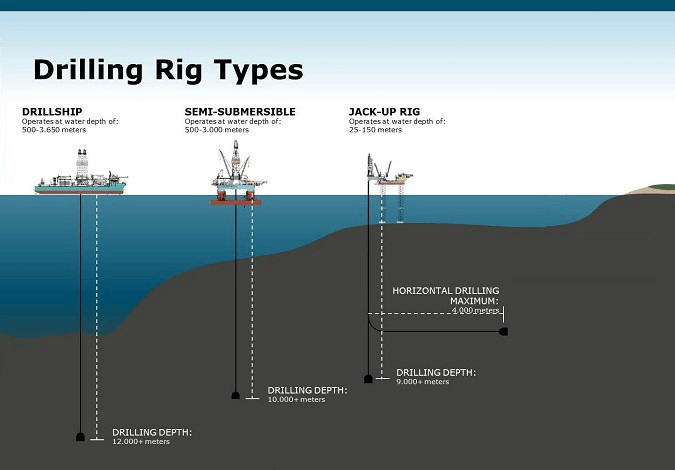

Voor een belangrijk deel werd de lente aangeblazen door oude, economische wetten. Rond 2020 begonnen de prijzen van windturbines en vooral zonnepanelen sterk te dalen. De prijs van fossiele energie ging juist omhoog: het internationaal energieagentschap (IAE) had al in 2018 gewaarschuwd dat de vraag naar olie sterk zou stijgen, terwijl het oppompen ervan juist achterbleef. Nu fossiel eenmaal in de beklaagdenbank stond, waren er domweg minder investeerders die de immense langetermijninvesteringen in olieprojecten nog aandurfden.

Ook Koning Steenkool begon te wankelen. Historisch was bijvoorbeeld vrijdag de 21ste april 2017, toen Groot-Brittannië voor het eerst sinds het begin van de industriële revolutie een heel etmaal lang geen steenkolen verstookte. Dat markeerde de trend: steeds meer sluitende kolencentrales in westerse landen, industrieën die overschakelden op gas, jaar na jaar minder steenkool uit de mijn. ‘Overal ter wereld is kolen op weg naar de uitgang’, signaleerde een onafhankelijke analyse al in 2017.

Tegelijk waren er de innovaties. Achteraf is het vreemd om je voor te stellen, maar destijds waren zonnecellen nog stijve, zwarte panelen die men op het dak schroefde. Zoals iedereen weet die weleens een emmer zonnecelpasta bij de bouwmarkt heeft gekocht: vandaag is dat wel anders. Of neem de zonnestroom opwekkende metaalcoating waarmee tegenwoordig haast alle auto’s, treinen, rails, verkeersborden en vangrails zijn bewerkt, de zonnedakpannen op uw dak of de zonneramen waardoor u naar buiten kijkt. Rond 2020 was het allemaal nog in ontwikkeling.

Een stomende, grijze, aan olie en steenkool verslaafde wereld moet het zijn geweest. Grafeenbatterijen, lithium-air-accu’s en zelfs siliciumbatterijen had men nog niet, zodat men uit wind en zon opgewekte stroom niet eens kon opslaan. Schepen voeren nog op stookolie in plaats van op microkernreactors en stroomvoorzienende skoonboxen. En omdat er nog geen betrouwbaar Europees netwerk van hogesnelheidslijnen bestond en zelfs de hyperloop nog in ontwikkeling was, was men voor vervoer aangewezen op benzineauto’s en vliegtuigen op kerosine.

Ook de velden met metershoog, wuivend oliezaad en olifantsgras in Frankrijk en Duitsland bestonden nog niet; de Tweede Groene Revolutie moest immers nog beginnen. Begin jaren twintig was men er weliswaar in geslaagd om met genetische modificatie gewassen te maken zoals supersnel groeiend oliezaad, snelgroeiend tarwe en zoutwaterbestendige rijst, maar in Europa aarzelde men nog om ze toe te passen. Het is aan de overtuigingskracht van oud-eurocommissaris voor klimaatzaken Jesse Klaver te danken dat Europa eind jaren twintig eindelijk zijn knellende beperkingen op genetische manipulatie afzwakte en de biotechnologie omarmde. Met als gevolg een revolutie in biobrandstof en bioplastics in Europa, een voedingsrevolutie in Afrika en Azië, en in landen als Frankrijk en Duitsland programma’s waarbij de overheid vrijkomende akkers terugkocht om te laten verwilderen.

Ook de Grote Ontdiering hielp mee. Vanaf ongeveer 2025 werden vleesvervangers en kunstvlees zo smakelijk en goedkoop, dat het ontdieren voor het eerst oversloeg van een tamelijk select gezelschap idealisten (‘vegetariërs’, noemden die zich destijds) naar de massa. Met als gevolg: slinkende veestapels, nog meer vrije landbouwgrond, drastisch minder mest en minder broeikasgassen zoals methaan en lachgas.

Oosten

Maar de grote klapper kwam uit het oosten. Daar was vooral China al jaren de belangrijkste aanjager van de almaar groeiende mondiale uitstoot van broeikasgassen. Maar dat was voor de smogrampen van de jaren twintig en de grote stormvloed van Guangzhou (900 duizend doden) en die van Mumbai (1,1 miljoen doden). China en India reageerden met enorme programma’s voor versnelde aanleg van kerncentrales, reusachtige wind- en zonneparken en grote herbebossingsprojecten. Onder meer de megazonneparken van Zuid-China, herkenbaar vanuit de ruimte als reusachtige bloemen en pandaberen, zijn in deze periode ontstaan.

Vanaf ongeveer 2035 begonnen in Afrika en Azië bovendien de eerste tekenen zichtbaar te worden van de grote depopulatie. In 2020 dachten veel experts nog dat de bevolking van Afrika zou verdubbelen, tot zo’n 2,6 miljard inwoners in 2050. Maar ze hadden buiten Sigrid Kaag gerekend, de visionaire D66’er en oud-minister die na de kabinetten Dijkhoff-1 en -2 aantrad als speciaal VN-klimaatgezant voor Afrika. In haar memoires Hoe de vrouwen de wereld redden brengt Kaag in herinnering hoe ze het klimaat verbond met ontwikkelingshulp. Zo ging ze ertoe over om miljarden dollars klimaatgeld in te zetten voor toiletten in India, kookstellen en waterleidingen in Afrika en vrouwenscholen in arme landbouwgebieden.

Stuk voor stuk meesterzetten, weten we achteraf. Door de kookstellen en de waterleidingen hoefden vrouwen geen hout meer te sprokkelen en water te halen en hielden ze tijd over voor onderwijs en betaald werk. Bovendien bleven de bossen rondom dorpen gespaard, wat weer hielp tegen verwoestijning, erosie en het verval van biodiversiteit. Door de toiletten hoefden vrouwen niet meer alleen het veld in, met als gevolg minder verkrachtingen en ongewenste zwangerschappen, maar ook een schoner milieu.

Gecombineerd met de vrouwenscholen ontstond er in het zuiden zo voor het eerst een generatie geletterde, werkende vrouwen, met onmiddellijk positief effect op de welvaart en de volksgezondheid. Waarna prompt gebeurde wat er al eerder in Europa en de snel moderniserende landen in Azië was gebeurd. Het aantal kinderen per gezin slonk, omdat werkende vrouwen pas op latere leeftijd kinderen krijgen, minder tijd hebben, en hun kinderen niet meer nodig hebben als oudedagsvoorziening.

In Afrika viel het geboortecijfer naar beneden van 5 kinderen per gezin in 2020 naar minder dan 2 in 2050; in India ging het kindertal van 2,3 in 2020 naar 1,6 een generatie later. De groei was een krimp geworden. Sigrid Kaag had de ‘populatiebom’ ontmanteld.

En er waren verbeteringen die zo weinig fotogeniek waren dat ze helemaal niet opvielen. In de jaren twintig en dertig verving men de fluorkoolwaterstoffen uit airconditionings, een internationale afspraak die men al in 2016 had gemaakt: een besparing van 90 miljard ton broeikasgas, en uiteindelijk liefst een halve graad opwarming minder. In Azië gingen boeren hun rijstvelden beter draineren: de methaanuitstoot nam tot 70 procent af.

En zo verder. In Afrika en Zuid-Amerika omarmden steeds meer landen en gemeenschappen de kleine, gesloten kernreactoren die vanaf midden jaren dertig in opkomst waren. In de steden werkte men aan schonere en overdekte rioleringen, beter openbaar vervoer en fiets- en wandelvriendelijke binnensteden. In de bouw herontdekte men bamboe als bouwmateriaal, gebruikte men beton met een lagere kalkgraad en ging men het binnenklimaat van openbare gebouwen en bedrijfspanden automatisch reguleren. Op het platteland beplantten boeren hun veeakkers met bomen – ‘silvopastuur’ – en kale vlaktes met vocht vasthoudende gaobomen. Het waren stuk voor stuk maatregelen die niet eens per se waren bedoeld voor het klimaat, maar om de gezondheid te verbeteren, winst te maken of het leven te veraangenamen. Maar het bijeffect – miljarden tonnen broeikasgas minder – was natuurlijk mooi meegenomen.

Zo begon de uitstoot van broeikasgassen na 2031 alsnog te dalen, later dan gehoopt, maar in hoger tempo dan voorzien. Niet als gevolg van een groots, wereldomspannend masterplan, maar door een opeenstapeling van duizend-en-een lokale maatregelen, vernieuwingen en ontwikkelingen. In Afrika en India was de sleutel welvaartsgroei; in het autocratische China gaf de volksgezondheid de doorslag; in Amerika kwam de duurzaamheid pas goed van de grond toen staten en bedrijven er onderling om gingen concurreren.

Er was nooit één oplossing geweest voor het klimaatprobleem; het waren er talloze.

Te somber ingeschat

Natuurlijk, voor de opwarming van de aarde maakte het aanvankelijk weinig uit. Velen herinneren zich nog de eerste zomer zonder ijs op de Noordpool in 2042. De dramatische bekendmaking, een paar jaar later, dat de ondiepe delen van het Great Barrier Reef voorgoed verloren waren. De grote rendiersterftes van de jaren dertig, het opdrogen van de Californische en Franse wijnstreken – ja, ooit verbouwde men wijn in het Rhônegebied – en natuurlijk de evacuatie van historisch Venetië, vanaf 2047 definitief ongeschikt verklaard voor bewoning.

Maar zelfs hier schatte men, weten we nu, de zaak in 2020 te somber in. De prognoses van begin 21ste eeuw gingen vaak uit van het somberste scenario, omdat risico-analyses nu eenmaal altijd moeten uitgaan van het ergst denkbare. 6 graden opwarming in het jaar 2100! Wel 2,5 meter zeespiegel erbij! Maar in werkelijkheid gingen de meer realistische scenario’s ook toen al uit van een opwarming die zou oplopen tot zo’n 3 graden in het jaar 2100 en een zeespiegel die in dat jaar hooguit 63 centimeter hoger zou staan.

In werkelijkheid bleek het mee te vallen. Zo brachten de vulkaanuitbarstingen van de Sabancaya in Peru en de Ol Doinyo Lengai in Tanzania behalve veel leed ook tijdelijke verkoeling, en was de zon minder actief, met als gevolg dat de opwarming langzamer ging dan de klimaatmodellen voorzagen. Toen de magische grens van 2 graden opwarming werd overschreden, was dat niet tussen 2030 en 2040 zoals men begin 21ste eeuw nog vreesde, maar pas in het jaar 2063.

Er was nog iets dat men begin deze eeuw schromelijk onderschatte – namelijk, het aanpassingsvermogen van de mens. Want geconfronteerd met hittegolven, overstromingen, noodweer, bosbranden, oogstproblemen, een stijgende zeespiegel en zwellende rivieren bleef men niet stilzitten, maar bood men, vaak met boerenverstand, de veranderingen het hoofd.

In Bangladesh gingen boeren in overstromingsgevoelige gebieden in plaats van kippen eenden kweken, die blijven bij watersnood tenminste drijven. In India haalde men een duizenden jaren oude bouwtechniek van woestijnbewoners van stal: bouw onder in het huis een waterbassin, dat scheelt bij hittegolven wel 20 graden. In het Caribische gebied bouwde men golfbrekers voor de kust en stormbestendiger huizen, in Zuid-Amerika beschermde men de kust met brede mangrovebossen en kunstmatige koralen, in andere landen verbood men eenvoudigweg nog huizen te bouwen in laaggelegen kuststreken.

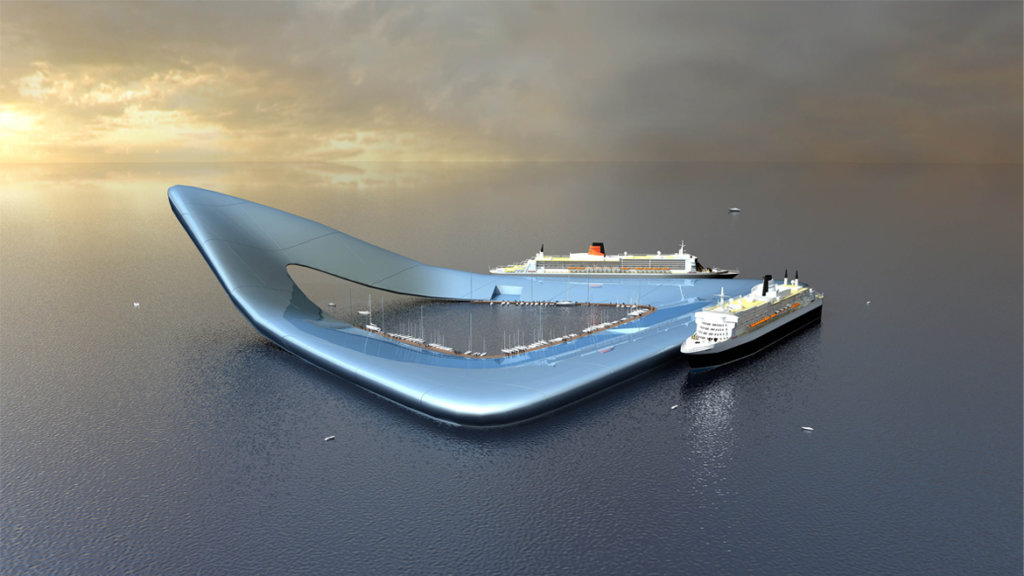

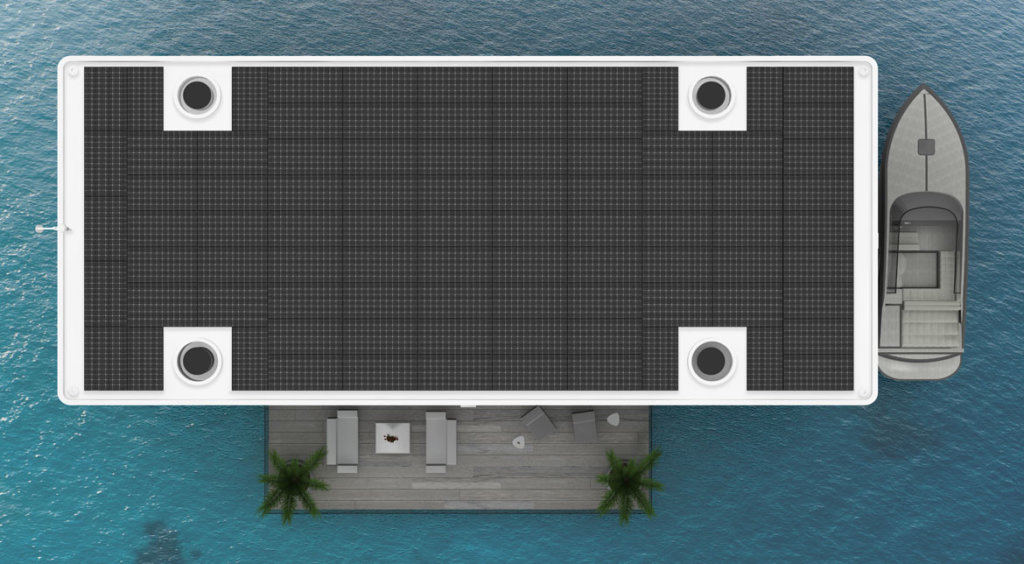

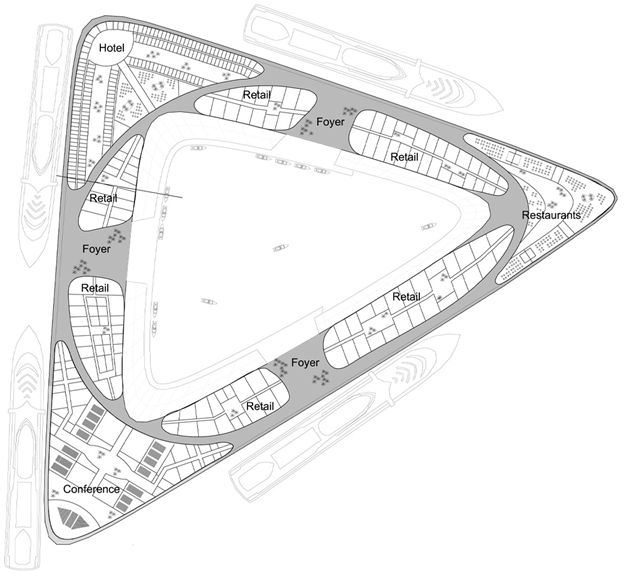

En in moderne landen als het onze paste men zich aan met ingenieursvernuft. Denk aan Schiphol in Zee, dat momenteel voor de kust wordt gebouwd op drijvend beton. Of aan de drijvende stad die de Nederlandse zeearchitect Koen Olthuis ontwierp, om de overlevenden van de watersnood van Miami te huisvesten.

Zo bouwend en innoverend en ploeterend bouwden we de wereld van 2069, het jaar waarin u dit leest. Volgens de meeste prognoses zal de temperatuur nog wat verder oplopen en glaciologen zijn bezorgd of de smelt van enkele cruciale gletsjers op Groenland en Antarctica nog wel te stoppen is. Maar nu steeds meer landen dankzij de enorme, lucratieve CO2-afvangprojecten die overal ter wereld zijn opgebloeid meer broeikasgassen aan de dampkring onttrekken dan ze erin stoppen, waarschuwen klimaatwetenschappers ook dat de temperatuur na 2100 weleens kan gaan dalen.

En zo komt het dat men afgelopen weekeinde de straat op ging, in de eerste klimaatmars sinds 2019, met borden als ‘Stop Global Cooling’ en ‘Red de planeet, ik krijg een kouwe reet!’ Vooral sinds de vorige winter zit de schrik er goed in. Voor het eerst sinds 2012 had Nederland een koudegolf, met alle gevolgen van dien: automobilisten wier stekker zat vastgevroren in de laadpaal, zonnepanelen die bedekt raakten onder de sneeuw, drijvende woonwijken met vorstschade.

Toeval natuurlijk, zo’n koudegolf, benadrukte premier Lotta Crok, ooit ’s werelds eerste ‘junior-fietsburgemeester’ en voorloper in de verduurzaming. Ook in ons warmere klimaat komen strenge winters nu eenmaal heel af en toe voor. Maar tegenstanders zijn geschrokken en verwijten haar de industrie de hand boven het hoofd te houden. Bedrijven als Tata Steel in IJmuiden en Dow Benelux in Terneuzen verdienen immers miljoenen aan de omzetting van hun CO2-uitstoot in kunststoffen en chemicaliën.

Ook elders begint de roep om maatregelen te klinken. Neem de hoogoplopende ruzie tussen Rusland en de CO2-afvangende golfstaten in het Midden-Oosten. Rusland, bezorgd dat zijn graanoogsten weer afnemen als het klimaat afkoelt, wil dat de golfstaten hun reusachtige CO2-afvanginstallaties uitschakelen. Maar de koolstofsjeiks willen er niets van weten: hun rijkdom berust immers op de handel in CO2-rechten. Grimmig werd de sfeer toen Saoedi-Arabië onlangs dreigde een zwavelzuurbom te laten ontploffen boven Rusland, die een afkoelende mist van zonlicht blokkerende druppeltjes in de stratosfeer zou verspreiden.

Ook in Amerika is het, twintig jaar na het uiteenvallen van de Verenigde Staten, weer onrustig. In een woedende livefeed herhaalde president Donald Trump III van de Verenigde Republikeinse Staten (VRS) vorige week zijn verwijt dat de Verenigde Democratische Staten (VDS) verantwoordelijk zijn voor de ‘klimaathysterie’ van destijds. ‘Straks vriest de Noordpoolroute voor de scheepvaart nog dicht’, aldus de president, die de VDS verdenkt van een samenzwering met China.

Het is anders gelopen dan men in 2020 verwachtte – simpelweg omdat de toekomst zich maar zelden goed laat vangen door de lijnen uit het verleden door te trekken. Het klimaat heeft de wereld drastisch veranderd, anders dan de klimaatsceptici van destijds verwachtten. Maar ook de pessimisten kregen ongelijk: ze onderschatten de flexibiliteit van de mens, onleefbaar of onbewoonbaar is de planeet niet geworden.

Hadden de mensen van twee generaties geleden dat maar geweten. Het had ze ongetwijfeld veel kopzorgen en frustraties bespaard.

Met speciale dank aan Tom Kram (ECN/PBL), Leo Meyer (Climate Contact Consultancy), Bart Strengers (PBL) en Detlev van Vuuren (PBL).

Verantwoording

Hoewel de hier geschetste toekomst uiteraard gefingeerd is, zijn veruit de meeste achterliggendecijfers, ontwikkelingen, namen, technieken en ideeën echt. Dit stuk is dan ook gebaseerd op tientallen studies, rapporten en artikelen en achtergrondgesprekken met experts. Omdat de meeste klimaatverhalen die tot ons komen uitgaan van de meest pessimistische voorstelling van zaken – wat bij een risico-inschatting logisch is – richt dit stuk zich juist op de middenscenario’s, die misschien dichter bij de werkelijkheid liggen.

Dieter Helm deed zijn uitspraak in de Financial Times, Klaas Dijkhoff sprak tegen de Telegraaf, het citaat van David Wallace-Wells komt uit zijn essay The Uninhabitable Earth, en Amory Lovins deed zijn uitspraken tegen Clean Energy Wire. Ook de micro-initiatieven, prognoses voor de energiemarkt en zaken als de uitstootcijfers van China zijn echt.

De uitstoot- en klimaatscenario’s waarop dit stuk is gebaseerd zijn ontleend aan de laatste twee IPCC-rapporten. Veel toekomstscenario’s gaan uit van de hoogste prognose (onder kenners bekend als RCP 8.5), maar dat scenario is omstreden omdat het uitgaat van onbeperkt beschikbare fossiele brandstoffen en ongebreidelde uitstootgroei. In dit artikel gaan we uit van een combinatie: tot 2030 haast ongeremde CO2-toename, daarna versnelde matiging naar de middenscenario’s, als allerlei nieuwe technieken tegelijk in werking treden, en na 2060 in diverse landen zelfs negatieve emissies.

De natuurrampen in Charleston, Mekka, Washington, Guangzhou, Mumbai, Californië, het Rhônegebied, Alaska, de Dode Zee en Rio de Janeiro vormen reële dreigingen en zijn ontleend aan diverse analyses van onder meer de Wereldbank en herverzekeraar Swiss Re. De ijsvrije Noordpool rond 2040, het verval van kwetsbare ecosystemen en koralen en de mogelijk onomkeerbare smelt van enkele grote gletsjers zijn prognoses van het IPCC.

Ook de menselijke aanpassingen aan klimaatveranderingberusten op waarheid. De golfbrekers, bouwverboden aan de kust, mangrovebossen en kunstmatige koralen in het Caribische gebied zijn gebaseerd op het initiatief Tarea Vida van de Cubaanse overheid. In India loopt een project om oude woestijnbouwtechnieken te herintroduceren, de eenden in Bangladesh zijn een proefproject, en architect Koen Olthuis van Waterstudio.NL geldt als een van de grote namen in het bouwen op het water.

Dan de nieuwe energietechnieken. Zonnecelpasta en zonnestroom opwekkende metaalcoating zijn twee oude dromen, die in onder meer Californië, Boston, Australië en Groot-Brittannië worden verkend. Van de talloze nieuwe batterijontwerpen die momenteel worden ontwikkeld, horen de grafeenbatterij, de lithium-air-accu en de siliciumbatterij tot de meest kansrijke. Met het oog op de lengte achterwege gelaten is onder meer waterstof, dat met name in het vrachtvervoer beloftevol is, en toepassingen van kunstmatige intelligentie.

De skoonbox is zomaar een van de vele aardige duurzame ideeën van eigen bodem: voorzie schepen van een zeecontainer vol opgeladen accu’s zodat ze een deel van hun reis op stroom kunnen varen. De hyperloop is een soort buizenpost voor vracht- en personenvervoer die in onder meer Delft steeds serieuzer wordt uitgewerkt.

Veel landbouwexperts gaan er vanuit dat er echt een nieuwe Groene Revolutie nodig is om de wereldbevolking te voeden en klimaatverandering het hoofd te bieden. Zoutresistente rijst werd afgelopen zomer gepresenteerd in China. Reusachtig oliezaad, olifantsgras en tarwe bestaan nog niet; de technieken om gewassen versneld te laten groeien worden al wel getest in andere planten. Een grote revolutie in kunstvlees, gekweekt dierweefsel uit het lab, verwacht de industrie pas over zo’n tien jaar.

De opmars van kernenergie in Afrika, de komst van kleine gesloten kernreactoren en de uitbreiding van kernenergie in China en India worden voorzien door het internationaal atoomagentschap (IAEA). Onder meer Egypte, Ghana, Kenia, Marokko, Nigeria, Niger en Soedan hebben een formele aanvraag voor kerncentrales ingediend bij IAEA. Pandavormige zonneweides in China bestaan overigens al.

De veronderstelde daling van het kindertal in Afrika is onderwerp van verhit wetenschappelijk debat. Een overzicht in The Lancet constateerde vorig jaar dat de bestaande prognoses de bevolkingsgroei consequent overschatten. Vrouwenemancipatie wordt door veel sociologen en economen inderdaad gezien als de sleutel tot bevolkingsafname. De aanleg van toiletten, keukens en waterleidingen duikt in veel analyses op.

De populatiebom verwijst het zeer beroemde milieuboek The Population Bomb (1968) van Paul Ehrlich; de titel ‘Hoe de vrouwen de wereld redden’ is een insidegrapje: lang was het de werktitel waaronder ik dit stuk werd aangekondigd bij de bijlages van deze krant.

De opgesomde ‘niet fotogenieke’ technieken, zoals fluorkoolwaterstoffen, silvopastuur, schonere riolen, andere bouwmaterialen, schonere rijstvelden, autoluwe binnensteden en automatische gebouwen, zijn ontleend aan de zogeheten Drawdown-lijst, een overzicht van pragmatische klimaatmaatregelen die deels onafwendbaar zijn. Dat fluorkoolwaterstoffen een halve graad zou schelen, is een bekende schatting.

De methaanuitstoot van rijstvelden wordt veroorzaakt door zuurstofloze modderbacteriën. Door de velden beter door te spoelen, zijn er daarvan minder, wat betere oogsten geeft en tot 2050 naar schatting zo’n 12 gigaton aan CO2-equivalenten aan broeikasuitstoot minder. Andere maatregelen zijn: betere bemesting, andere rijstrassen, minder bodemverstoring.

Donald Trump heeft een zoon én een kleinzoon genaamd Donald. Lotta Crok, dochter van klimaatpublicist Marcel Crok, werd in Amsterdam vorige zomer echt ’s werelds eerste junior-fietsburgemeester.

Click here to read the pdf

Clich here to read the article on the source website

Source : Waterstudio

Source : Waterstudio