Designed in a pattern similar to brain coral, the city will consist of 5,000 floating units including houses, restaurants, shops and schools, with canals running in between. The first units will be unveiled this month, with residents starting to move in early 2024, and the whole city is due to be completed by 2027.

How floating architecture could help save cities from rising seas

By Kate Baggaley

NBC

From New York to Shanghai, coastal cities around the world are at risk from rising sea levels and unpredictable storm surges. But rather than simply building higher seawalls to hold back floodwaters, many builders and urban planners are turning to floating and amphibious architecture — and finding ways to adapt buildings to this new reality.

Some new buildings, including a number of homes in Amsterdam, are designed to float permanently on shorelines and waterways. Others feature special foundations that let them rest on solid ground or float on water when necessary. Projects range from simple retrofits for individual homes in flood zones to the construction of entire floating neighborhoods — and possibly even floating cities.

“It’s fundamentally for flood mitigation, but in our time of climate change where sea level is rising and weather events are becoming more severe, this is also an excellent adaptation strategy,” says Dr. Elizabeth English, an associate professor at the University of Waterloo School of Architecture in Ontario. “It takes whatever level of water is thrown at it in stride.”

NEW KIND OF FLOOD READINESS

From ground level, amphibious houses look like ordinary buildings. The key difference lies with their foundations, which function as a sort of raft when the water starts to rise.

In some cases, existing homes can be retrofitted with amphibious foundations to give people in flood-prone areas a less costly alternative to moving or putting their homes on stilts, says English, founder of Buoyant Foundation Project, a nonprofit based in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana and Cambridge, Ontario. “What I’m trying to do is to take existing communities and make them more resilient and give them an opportunity to continue to live in the place that they’re intimately connected to,” she says.

There are also new constructions built with amphibious foundations, such as a home designed by Baca Architects on an island in the River Thames in Marlow, England. When waters are low, the house rests on the ground like a conventional building; during floods, it floats on water that flows into a bathtub-shaped outer foundation.

Amphibious architecture isn’t about to displace conventionally designed buildings. But experts say it could become the norm in parts of Virginia, Louisiana, Alaska, and Florida, and other areas that are vulnerable to rising seas. “For some communities this might be a saving grace,” says Illya Azaroff, director of design at New York-based +LAB Architect PLLC and an associate professor of architecture at the New York City College of Technology.

FLOATING HOMES

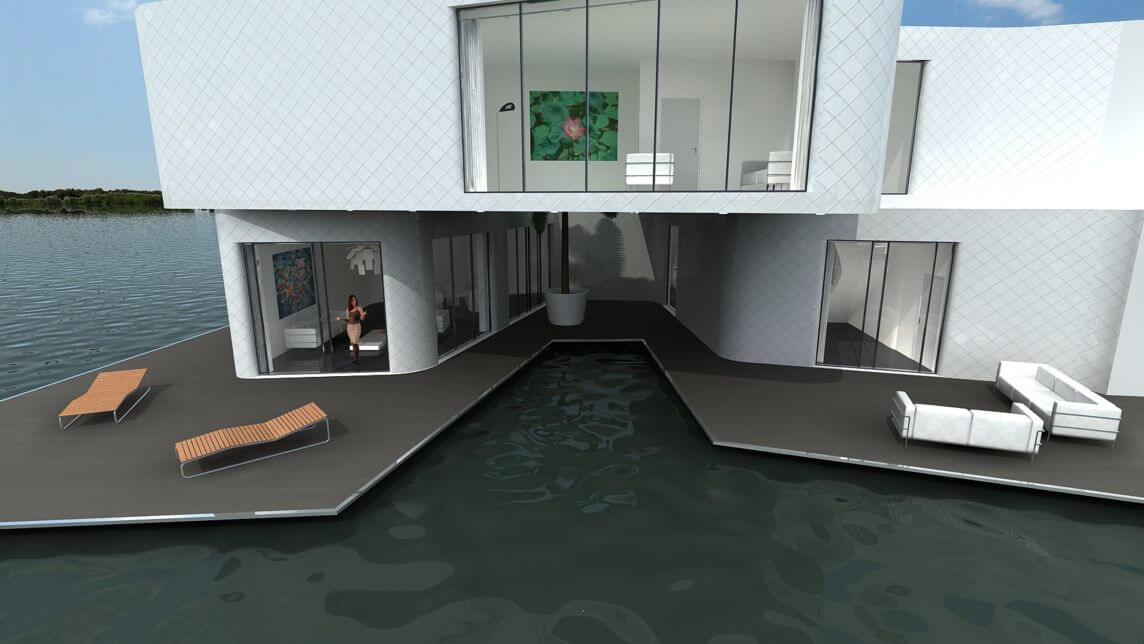

Other architects are taking things a step further and building on the water itself. The Netherlands is a hotspot for such floating construction. Waterstudio, a Rijswijk-based architecture firm, recently designed nine floating homes for the town of Zeewolde. The homes look a bit like oversized floating houseboats.

Waterstudio has also designed a number of floating homes for Amsterdam’s IJBurg neighborhood. Soon these will be joined by a floating housing complex designed by the Dutch firm Barcode Architects and the Danish firm Bjarke Ingels Group. When construction is completed in 2020, the complex will have 380 apartments as well as floating gardens and a restaurant.

Floating buildings and neighborhoods are not a new idea, of course. Vietnam and Peru, among other countries, have had floating communities for centuries. But floating architecture could allow cities around the world to grow and evolve in new ways, says Waterstudio founder Koen Olthuis.

Olthius envisions cities with floating office buildings that can be detached and rearranged as needed. “It can be that you come back to a city after two or three years and some of your favorite buildings are in another location in that city,” he says, adding that buildings might be moved close together to conserve heat and separated when summer arrives.

SPREADING OUT

Floating architecture can do more than prevent flood damage. By allowing the construction of buildings over water, it can give cities additional room to grow. Waterstudio is collaborating with developer Dutch Docklands on a planned community in the Maldives that will include 185 floating villas. The flower-shaped development will have restaurants, shops, and swimming pools.

The firms are also collaborating in the Maldives to build private artificial islands that will be anchored to the seafloor. The idea is to provide new places to live for residents of the low-lying islands, which are at risk of being swallowed up by rising seas. “We will let the commercial project show that the construction can work and then work with the government to help the local community,” Jasper Mulder, vice president of Dutch Docklands, told Travel + Leisure.

The islands are also meant to offer a sheltered new habitat for marine life.

There are also plans for entire floating cities. The Seasteading Institute, a San Francisco-based nonprofit, hopes to attract 200 to 300 residents for a floating village scheduled for completion in the waters off Tahiti by 2020. Homes and other buildings in the community will be constructed atop a dozen or so floating platforms connected by walkways. Eventually, the institute hopes to create communities built from hundreds of platforms with millions of residents.

“I don’t know if amphibious or floating architecture will go that far, but it is within the realm of possibility,” Azaroff says. “The overarching goal is to, one, keep people safe and, two, to allow the natural cycles to continue. Floating architecture allows you to do that in a really profound way that we didn’t have before.”

Continuing Education: Floating Buildings

By Katharine Logan

Architectural record

April.1.2017

As the ice melts and the seas rise, building on waterfront and flood-prone sites begins to look a lot like foolishness, yet backing away from the water takes more willpower than most cities and towns can muster. Ever since the first settlements took root on flood-fertilized riverbanks, next to the water is where people have always wanted to be.

The floating houses designed by Waterstudio, which make up a neighborhood on Amsterdam’s Lake Ijssel, have “foundations” formed in a single pour to eliminate joints.

Photo © Waterstudio

The Waterstudio’s Villa De Hoef, in the Netherlands, normally sits on dry ground alongside a waterway. But when it floods, the house floats.

Photo © Waterstudio

A developer is currently seeking zoning approval to build 29 Waterstudio-designed private floating islands on an inlet north of Miami Beach.

Image © Waterstudio

Denizen Work’s proposal for a floating and relocatable church for the Diocese of London features a roof composed of a pair of asymmetrical, pleated wings. These are lifted, like the pop-top of a vintage camper, once the vessel is docked.

Denizen Work’s proposal for a floating and relocatable church for the Diocese of London features a roof composed of a pair of asymmetrical, pleated wings. These are lifted, like the pop-top of a vintage camper, once the vessel is docked.

Image © Denizen Works

Denizen Work’s proposal for a floating and relocatable church for the Diocese of London features a roof composed of a pair of asymmetrical, pleated wings. These are lifted, like the pop-top of a vintage camper, once the vessel is docked.

Image © Denizen Works

Carlo Ratti’s scheme for Currie Park in West Palm Beach, Florida, consists of interconnected piazzette. The park, which will float on Lake Worth Lagoon, incorporates amenities such as a restaurant, an amphitheater, and a circular pool.

Image © Carlo Ratti Associati

Carlo Ratti’s scheme for Currie Park in West Palm Beach, Florida, consists of interconnected piazzette. The park, which will float on Lake Worth Lagoon, incorporates amenities such as a restaurant, an amphitheater, and a circular pool.

Image © Carlo Ratti Associati

So what are the options for staying put and living with water rather than moving away from it? They range from keeping water out— with barriers, stilts, and raised ground planes —to letting water in, with ground floors designed for periodic inundation, to, ultimately, rising above it all, with floating architecture. Yes, really. “Whether it’s New York or London, Bangkok or Dhaka, all these cities are growing, all these cities are next to the water, and all are threatened by the water,” says Koen Olthuis, founding principal of Netherlandsbased Waterstudio. “Floating developments can be part of the solution.”

The technology of floating architecture isn’t new. Each of the projects considered here uses tried-and-true technology adapted from marine applications to achieve its unusual results, whether it’s a floating house, an island, a church, or a plaza.

Houseboats, for example, have been around for centuries, and the floating houses that make up a neighborhood in Ijburg, under development in Amsterdam’s Lake Ijssel, are “really just better houseboats,” says Olthuis, “built to the same standards as a house on land, using the same methods and materials.”

For all their similarities to houses on terra firma, however, the float houses Olthuis has designed for Ijburg differ in a crucial aspect: their buoyant “foundations,” or lower levels. Formed in a single pour to eliminate joints, and emphatically free of cracks, a prefabricated concrete tub—or hull—is designed to displace a volume of water with a weight equivalent to the weight of the house. The hull is submerged the depth of half a story and secured to telescoping piles at diagonally opposite corners, allowing the house to rise and fall with the water but not wander about. (Typically, bedrooms are located on the partially submerged level, and the water reduces heating and cooling loads on the house.) As a refinement, automatic air-water balancing tanks help keep the house level when the residents invite more than a few friends to a party.

A buoyant foundation can also be used to build amphibious architecture on flood-prone land. Amphibious architecture retains a connection to the ground under ordinary circum- stances and floats as high as needed when flooding occurs. As a flood-mitigation strategy, amphibious architecture works with natural cycles, instead of trying to resist them.

Waterstudio’s 1,440-square-foot Villa De Hoef, for example, usually sits in a garden beside a waterway in the small Dutch town of De Hoef. When the waterway floods, which happens every 10 years or so, the house floats; as the flood recedes, the house returns to its original position. With a maximum anticipated flood level for the site of only 4 feet, the project’s engineers deemed it safe to tether the house with cables and surround it with a wooden deck, in preference to telescoping piles. A skirt of nylon net prevents flood debris from becoming lodged beneath the house. “Low-tech, low-maintenance,” says Olthuis. Maintaining the amphibious system requires periodic visual inspection of the cables and deck, and, every five years, a recalculation of the house’s added or moved live load to determine and adjust its center of gravity. This is in case the occupants have accumulated more belongings or rearranged the furniture.

Expanding the applications for floating architecture, Waterstudio is now designing private islands that will float on a patented platform moored to the seabed. With projects under way for Dubai and the Maldives, the firm’s Amillarah project is currently seeking zoning approval for a “villa flotilla,” as the Miami Herald dubbed the proposal, with 29 floating islands on Maule Lake, an inlet north of Miami Beach.

Expected to sell for about $12.5 million each, the floating islands will make only a few hundred very wealthy people happy, notes Olthuis. Ultimately, however, he sees a more egalitarian future for the technology, as a solution for people worldwide who live in slums that are close to open water and vulnerable to flooding. Improving these so-called wet slums is almost impossible, since governments are unwilling to condone illegal settlements by sponsoring upgrades and because lenders are unwilling to invest in something that will be flooded out.

But, building on their experience developing floating islands, Waterstudio has proposed simple schools and critical infrastructure, such as water-treatment plants, that would sit on small floating islands and be connected to the slums. The firm has recently completed a prefabricated floating school that will be shipped to Dhaka and assembled next to a wet slum there. Such facilities typically qualify as temporary solutions, which makes them acceptable to government officials. They can be relocated as needed, retaining their value, which makes them attractive to investors. And they can be leased for limited periods, which makes them accessible to the communities that need them. “It’s a delicate system, where you get investors, regulators, and users all together to improve life in these wet slums,” says Olthuis.

A versatile, affordable, and mobile solution is exactly what the Church of England’s Diocese of London was looking for when it commissioned London-based Denizen Works to design a floating church and community hub to support the diocese’s outreach program along London’s waterways.

With the rocketing cost of land, London’s waterways are the busiest they’ve been since the industrial revolution, with a floating bookshop, cinema, restaurants, and even a puppet theater, as well as a significant residential component. The activity on the water could soon be eclipsed, however, by the activity of new development along the water’s edge. In 2015, the mayor’s London Plan identified key brownfield “Opportunity Areas,” many of which lie along these waterways.

With its floating church, the diocese is responding both to the anticipated growth of new waterfront communities on brownfields and underdeveloped lands, and to the difficulty of finding space in the rapidly redeveloping city for a new church. “We spotted this opportunity,” says Hayley Harding, program management officer with the diocese, “and felt that it was something that could grow and support development and change.”

The priority for the diocese is to establish a presence in emerging communities—on and beside the water—as early as possible, and in a space that the local parish can own and manage, running both secular and worship activities as it sees fit. The floating church will moor at key regeneration sites for threeto five-year periods, offering services, and developing relationships with growing communities. Ultimately the Diocese will evaluate whether and how to build a permanent facility.

The competition brief for the project called for a multifunctional space that could accommodate a diverse program of worship and celebrations, art exhibitions, yoga classes, parent-and-toddler groups, and supper clubs. “They’re not just looking to bring the church to these emerging communities,” says Murray Kerr, director at Denizen Works, “but a sense of community as well.”

Denizen’s winning scheme, developed in collaboration with Turks Shipyard and based on a traditional wide beam canal boat, provides 500 square feet of interior space, plus decks, in a vessel that is 60 feet long and 12 feet wide but less than 6 feet above the waterline, so that it can easily clear the London canal system’s low bridges. The design, which is projected to cost about $370,000, includes an innovative roof that generates a play of light and volume. Once the vessel is docked, the roof’s two asymmetrical segments can be raised to reveal pleated sides much like the bellows of a church organ (or, more prosaically, the pop-top of a vintage camper). The longer wing shelters the hall, while the shorter one covers the ancillary spaces, including a kitchen and an office. Crafted from resinimpregnated sailcloth, the translucent bellows will provide a soft, ambient light during the day and act as a Chinese lantern at night, says Kerr, “creating a warm, inviting glow for passersby and imbuing the interiors with a celestial quality.”

“They delivered something we weren’t expecting,” says Harding. “This beautiful volume is something that can be a sacred space as well as a community asset. And Denizen’s partnership with a shipyard demonstrates that it is viable.”

The church will be Denizen’s first project to float. By contrast, the work of Turin, Italy– based Carlo Ratti Associati demonstrates an abiding fascination with water, so it’s no surprise that the firm’s 2016 master plan for the Currie Park waterfront at West Palm Beach, Florida, incorporates a significant water-based element. What is unexpected is the use of a technology adapted from submarines to carve volumes of habitable space into the surface of the Lake Worth Lagoon.

“One of the aims of our work is to imagine an architecture that adapts to human need, rather than the other way around—a living, tailored space that is molded to its inhabitants’ needs, characters, and desires,” says Carlo Ratti, the firm’s founding partner and the director of the Senseable City Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “Water is a reconfigurable material, and it allows us to develop adaptive, ‘fluid’ designs.”

The plan envisions a floating plaza (or, perhaps more accurately, a series of floating piazzette) projecting out onto the lagoon. The plaza will hang in the water, with its surface about 5 feet below sea level, providing views across the water from this unusual perspective. The project is anticipated to have virtually no environmental impact, floating in the lagoon just like a midsize boat, using no fuel, and discharging nothing into the water.

As part of the 50-acre master plan, the plaza will connect to West Palm Beach’s city center along a pair of leafy promenades, and will incorporate such facilities as an organic restaurant with its own hydroponic cultivations, a circular pool, and an amphitheater.

Now in design development while seeking municipal approvals, the plaza will consist of a series of lightweight steel modules composing a peninsula of about 5,000 square feet. The structure’s deck will be made of galvanized steel (similar to boat construction), with teak finishes. Beneath the plaza, a series of sensoractivated air-water chambers will open and close, releasing or taking in water according to the number of people walking on the surface, and adjusting for a height differential of up to 20 inches, which accommodates loading changes of up to 100 pounds per square foot. “The use of responsive digital technologies is often employed to introduce movement and complexity to static architecture,” says Ratti, “but it can equally be used to achieve stasis and equilibrium within a moving landscape.”

With this project, West Palm Beach aims to reclaim its connection to the natural environment it is part of, give shape to a vibrant new district, and, says Ratti, “radically redefine the relationship between architecture and water.” Ratti has identified the theme that unites these disparate examples of floating architecture: a floating plaza that engages with water in a playful new way; a floating church that enables an ancient institution to reach out to its changing city; floating islands that uplift the few and the many; amphibious architecture that celebrates a river even in flood; and a floating neighborhood that provides a city with new “ground.” All of these offer new possibilities for changing waterfronts and new possibilities for us to stay where we really want to be—by the water.

A Future Afloat

By Erik Bojnansky, BT Senior Writer

Biscayne Times

volume 15 issue 1

Photo Credits: Waterstudio

IT MAY SOUND CRAZY TODAY, BUT DESIGNERS AND ENGINEERS AROUND THE WORLD ARE ALREADY EMBRACING LIFE ON THE WATER

For more than 14 years, Dutch architect Koen Olthuis has been designing buildings that float. His portfolio includes the construction of 200 floating homes and offices in the Netherlands.

Later this year, luxurious floating islands designed by his Rijswijkbased architecture firm, Waterstudio, will be shipped from the Netherlands to Dubai and the Maldives. Olthuis is also experimenting with floating computer classrooms and other facilities called City Apps that he hopes will soon be transported to floodprone Bangladesh. And he’s in contact with a New Jersey developer who wants to transform the Lincoln Harbor Yacht Marina into a floating residential community with views of the Manhattan skyline.

Olthuis has other ambitious ideas, too. On his architecture firm’s website, www.Waterstudio.nl, you’ll find plans for floating apartment buildings, floating restaurants, floating hotels, floating cruise ship terminals, floating places of worship, floating beaches, floating golf courses, floating “sea trees” for animals, floating facilities (City Apps) for flooded slums, and floating islands for he very wealthy.

“When we started in 2003, we were the only office that was 100 percent into floating structures,” says Olthuis. “Everybody said we were crazy. But we saw the market, and today there are many, many architects working on floating structures in Holland and in Europe. It has become more mainstream.”

Olthuis also wants to bring his designs to Miami’s urban areas and show that water, especially in the form of rising sea levels, doesn’t have to be an obstacle to future development. It can be an asset.

“The reason I’m an architect is that our cities are not perfect. They don’t function as well as they should,” says Olthuis, who floats his structures on concrete box foundations filled with Styrofoam. “I think that water is the next ingredient to improve the performance of cities.”

Rising seas pose a major threat to Greater Miami. Within the next 80 years, climate change may result in ocean levels that are up to seven feet higher than today, washing out huge sections of flat Florida. But Olthuis feels his floating structures can literally rise to the challenges that tides could bring in the coming decades. And for the present, he argues, floating neighborhoods can provide greater flexibility for urban planners, especially in places like Miami and Manhattan, where vacant land is scarce and expensive.

So far, Miami has not taken well to his plans. His idea to create a floating Major League Soccer stadium for David Beckham in downtown Miami didn’t sail. And his proposal to build a floating parking facility for the American Airlines Arena ran aground.

And then there is Maule Lake, a privately owned body of water in North Miami Beach bordering the upscale neighborhood of Eastern Shores. Business associates of Olthuis, through the Dutch Docklands Company, were contracted to buy the lake. It’s here that Olthuis planned to anchor 29 artificial islands each about 7000 square feet, with a fourbedroom house, vegetation, swimming pool, and a couple of boat docks and sell them for $12.5 million apiece. A 30th island, called an “amenity island,” was to feature a clubhouse. The floating community would be called Amillarah. (The project is named after another Dutch Docklands venture, Amillarah, in the Maldives. The word amillarah means private island in Maldivian, according to Dutch Docklands.)

Many Eastern Shores homeowners were horrified at the thought of 30 private islands being built in what they considered their backyard. Among their fears: that the islands would become projectiles during powerful hurricanes, that they would ruin the aesthetics of the neighborhood, and that they would attract throngs of gawkers.

“We don’t want it. We’re going to fight against it. And we’re not going to let it happen,” said Chuck Asarnow, president of the Eastern Shores Homeowners Association, in an interview with the BT in May 2015. In response to the outcry, the North Miami Beach City Council (four members of which, including Mayor George Vallejo, lived in Eastern Shores) declared Maule Lake to be a “conservation area” in July 2015, thus prohibiting development.

But Amillarah in North Miami Beach may not be dead in the water. This past October, Scott Weires, an attorney representing Raymond Gaylord Williams, the owner of Maule Lake, sent North Miami Beach officials a letter announcing his client’s intention to sue under Florida’s Bert J. Harris, Jr. Property Rights Protection Act for $37 million in damages if the city doesn’t rezone the lake. Maule Lake, incidentally, was a rock quarry used by the Maule Rock Mining Company, run by E.L. Maule, in the early 20th century. Williams is a descendant of Maule.

Under the Harris Property Rights Protection Act, a private property owner can seek relief when a governmental body imposes restrictions on the use of that property.

In a February 2, 2017, memo to NMB officials, city attorney José Smith stated that the Williams claim “lacks both merit and validity,” and that the law firm of Weiss Sorota Helfman had been retained to represent the city. Eastern Shores residents remain defiant, insisting that there were never any rights to build on the lake because it was never zoned for development.

“That took them awhile. I thought it was over,” says Fortuna Smukler, chair of the Eastern Shores Crimewatch committee, regarding Williams’s filing of a Harris action 18 months after the city designated the lake a conservation area. “I have confidence in our city attorney. He originally said that Williams won’t have a claim, and I believe him.”

Adds David Templer, an attorney and board member of the Eastern Shores Homeowners Association: “It’s pretty interesting that we use up all the waterfront land [for development] and, hey, now we can use up the water, too.” Weires contends that Williams has the right to develop the lake he has inherited, or to sell it with the development rights attached.

“Our investigation has revealed that these privately owned lands are not environmentally restricted and were never properly zoned by the city,” Weires tells the BT. “As a result, we contend that our client has a constitutional right to develop the entire parcel any way he wishes.

“That said,” Weires continues, “our client has always been, and continues to be, open to discussing possible resolutions with the city that would allow for the reasonable development of some portion of the 117 acres, while maintaining a large amount of the open water.”

And Olthuis? He’s still interested in building floating homes for Maule Lake. It will be a chance to showcase his buoyant residences, designed to withstand the strongest hurricanes, as an environmentally friendly method of developing submerged real estate.

“Miami can test these kinds of floating structures in order to use them on a bigger scale in the near future,” he says.

Olthuis isn’t the only person seeking to build innovative structures directly on the water. There are a number of bold designs floating around.

Among those proposing plans is the Californiabased Seasteading Institute, a nonprofit organization that received significant early funding from libertarian by Libertarian billionaire Peter Thiel “to provide a machinery of freedom to choose new societies on the blue frontier.” This past January, the Seasteading Institute signed a memorandum of understanding with the French Polynesian government that aims to build the first phase of a selfsustaining, floating village within the territorial waters, which would also have its own Special Economic Zone and “unique governing framework.”

The village, estimated to cost between $10 million and $50 million, is being designed by Blue 21, a Dutch engineering firm that also specializes in building floating structures. It will be constructed by Blue Frontiers, a forprofit company spun off from the Seasteading Institute. Not to be confused with the nonprofit marine conservation group Blue Frontier Campaign, the Seasteaders’ Blue Frontiers aims “to develop and construct floating islands and to operate the seazone.” The institute envisions thousands of seasteads “across French Polynesia, the Pacific, and the world” that would “test new ideas for government.”

Doug Pope, a Jacksonvillebased shipwreck treasure hunter, also wants to jumpstart plans to create his project, Oceana Water Resort, a 50unit hotel sitting on an elevated platform and rising six stories above the Gulf of Mexico, 16 miles northwest of Key West. It would be situated in water 5560 feet deep, he told the Miami Herald in February, and sit on pilings that could be raised and lowered as needed. Oceana, Pope declares, will be designed to withstand winds up to 200 miles per hour and will be powered by generators in concert with wind and solar power.

And in Riviera Beach in Palm Beach County, Fane Lozman, a former outspoken North Bay Village activist, wants to build stateoftheart stilt homes capable of responding to the tides, on 25 acres of prime submerged real estate that’s just a few miles from President Donald Trump’s MaraLago.

Steve Israel, a real estate investor and developer, says Mother Nature inspired his desire to turn Lincoln Harbor Yacht Club in Weehawken, New Jersey, a marina he has owned for 25 years, into a floatinghome community.

“Hurricane Sandy flooded everything around us, including things that were anchored on the ground,” Israel recounts. “But all my boats floated up. We have high pilings and no damage.”

Olthuis has already designed a “doublestory floodresistant yacht” without motors that can serve as floating homes for Lincoln Harbor. But because New Jersey bans stationary houseboats, Israel is also seeking someone who can build luxury “livable yachts” with engines and limited mobility at least until the houseboat law is overturned.

“This is what I am mostly excited about,” Israel says, touting the marina’s views of Manhattan and

proximity to a New JerseyNew York ferry. Israel sees this as an opportunity to destroy a nationwide stigma against houseboats, and a means to prepare for a wetter future. “Both cities [New York and Miami] are likely to be flooded in the near future,” he says. “Why assume that the places we live have to be anchored to the ground?”

If his Lincoln Harbor venture works out, Israel may try something similar for the marina he’s redeveloping in Fort Myers near the site of a future 18story condo he may codevelop or sell to another investor. (The proposed condo has parking on the first three floors, Israel says, partly as a precaution against future flooding events.) Israel would also love to set up a floating community in Miami: “I do believe Miami is very ripe for the same kind of deal.”

Building directly on the water isn’t a new thing. There’s Olthuis anticipated a parking crunch with this structure floating next to American Airlines Arena.

evidence that people have lived in stilthouses on the shores of lakes and seas since prehistoric times. And there have been floating villages in Asia for centuries.

In Florida, the waterways of Miami and Miami Beach were once filled with houseboats, says Paul George, a historian affiliated with the HistoryMiami Museum, and a “It kind of evolved,” George says, noting that the first houseboats on the Miami River, in the 1920s, were anchored near Grove Park in today’s Little Havana. “My sense is that some of these people were Northerners,” he says. “They were staying on houseboats, staying during the season, which is wintertime in Miami.” By the 1930s and 1940s, there were hundreds of houseboats on local waterways.

By the 1950s and 1960s, houseboats were also tied to docks in Miami Beach and North Bay Village, inspiring a television show in the early 1960s called Surfside 6, about a detective agency based on a houseboat moored across the street from Miami Beach’s Fontainebleau Hotel.

Just off of Key Biscayne, in the shallow waters of Biscayne Bay, another aquatic community sprouted, called Stiltsville. Its origins can be traced to 1933, when Crawfish Eddie Walker turned a wrecked ship into a spot where he could sell chowder and bait to recreational fisherman. “He was a great storyteller,” George says.

Within a few years, Walker had neighbors. Various clubs, restaurants, lodges, and weekend homes were established, either on grounded ships or in stilt houses that rose ten feet or more above sea level.

At its height there were 27 houses and converted shipwrecks in Stiltsville. But the community’s structures were gradually weeded out by hurricanes. Prior to Hurricane Betsy in 1965, there were 24 businesses operating on old ships and stilthouses, notes George. After Betsy there were just 17.

Permits for new structures stopped after Biscayne National Park took over Stiltsville in 1980. The businesses and residences that remained were allowed to operate another two decades. Then along came Hurricane Andrew, which whittled the houses down to seven. After a campaign was launched to save the structures, the remaining seven houses are now shuttered, preserved relics that are maintained by their former owners, now referred to as “caretakers.”

Hurricanes slashed the number of houseboats in Miami and Miami Beach, too. That and a growing stigma toward houseboats. Some of the vessels on the Miami River became unsightly hunks of junk. George says the houseboat dwellers were often referred to as “river rats.” By the 1980s and 1990s, the City of Miami was outlawing them on the Miami River and other waterways. Miami Beach passed similar legislation. And marinas? They started turning away houseboats and other vessels used as fulltime residences.

It’s thanks to Fane Lozman that Dutch Docklands now has some added legal support in its pursuit of the Maule Lake project. Lozman, the creator of Scanshift, a software program that keeps tabs on the stock market, fell in love with the Miami houseboat lifestyle more than a decade ago and fought all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court for his right to continue living on one.

Lozman has a reputation for fighting. In 2003, when his first houseboat was tied up in North Bay Village, he tangled with Al Coletta, a politically influential property owner who allegedly threatened Lozman when he asked if a ramp could be provided for a disabled elderly houseboat owner.

Soon Lozman was fighting Coletta’s allies at North Bay Village City Hall. In November 2003, Commissioner Robert Dugger was arrested for official misconduct based on evidence Lozman collected showing that Dugger failed to disclose his financial connections to Coletta. The Seasteading Institute hopes to build a floating city in French Polynesia, like this concept designed by Blue21.

In April 2004, police Chief David Heller resigned and Mayor Al Dorne and Commissioner Armand Abecassis were arrested for actions related to an obscene threatening cartoon left anonymously in Lozman’s mail.

Lozman might still be in North Bay Village if it hadn’t been for Hurricane Wilma in October 2005. His houseboat survived, but 41 of the neighboring houseboats sank, and the marina where he docked was destroyed. In the aftermath, he discovered that many marinas were reluctant to accept houseboats for fear of turning them into “aquatic trailer parks.”

The only place that would accept Lozman’s houseboat was a marina owned by the City of Riviera Beach, 75 miles up the coast from North Bay Village. Within two months of relocating, Lozman learned that the city planned to condemn the marina as part of a controversial $2.3 billion waterfront redevelopment plan. Lozman sued to stop the project. Riviera Beach officials responded by claiming that Lozman hadn’t paid his dock fees, an accusation he denied. In 2009, after a circuit court judge ruled that his motorless houseboat was a “vessel,”

Riviera Beach officials seized his houseboat under admiralty law, towed it away, and destroyed it. Lozman, in turn, appealed the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 2013, the court ruled that Lozman’s houseboat was, indeed, a home and not a vessel.

Although Lozman says he’s still litigating to be compensated for his home’s destruction, it was his case that has helped Koen Olthuis’s Dutch Docklands associates argue that the proposed floating islands in Maule Lake will be, in fact, floating properties. Lozman bought another houseboat, a circa1967 twostory home that was once featured in a Frank Sinatra crime drama called Lady in Cement. Unable to find another marina, he kept it anchored in Biscayne Bay near in the 79th Street Causeway.

Then in 2014, he was contacted by the owners of 200 acres of submerged property on the Intracoastal Waterway, along A1A in Singer Island, a narrow strip of land that is now the most affluent part of Riviera Beach.

“They were wealthy people whose family was paying taxes on it for the past 94 years,” Lozman says. The family was so enamored of his “David versus Goliath Doug Pope’s vision of his Oceana Water Resort, a 50unit hotel 16 miles northwest of Key West in the Gulf of Mexico. story,” as Lozman puts it, that they offered to sell him 25 acres of their submerged land for $250,000. The deal closed later that year.

By the summer of 2016, Lozman had triumphantly towed his second floating home, the Sinatra houseboat, adorned with a banner proclaiming his Supreme Court victory, and anchored it at one of his submerged land parcels. Lozman also announced his intention to build a community of floating homes on his 25 acres.

His waterfront condo neighbors, who lived along A1A, were less than thrilled. Last July, Singer Island residents, fearful of losing their views and property values, petitioned the Riviera Beach City Commission to not grant Lozman street addresses.

Lozman says his neighbors’ expressions of dismay weren’t limited to petitions or pleas to local media. A couple of men in a boat tried to hit him with a drone, Lozman recounts, and someone broke into his houseboat and left garbage bags filled with feces.

“One woman came over and tried to buy my property,” Lozman remembers. When he said no, “she started cursing at me. She wouldn’t take no for an answer.” (Emails to the Singer Island Homeowners Association, as well as calls to the association’s president, went unanswered by deadline.)

This past August, Lozman’s Sinatra houseboat sank. The cause isn’t known, but Lozman says the fact that a door to the second floor of his houseboat was open, and that several hatches were missing, indicate an intruder may have sunk it. Witnesses also saw people with flashlights near his property prior to the sinking, he adds.

In spite of his best efforts, the home couldn’t be salvaged. The matter is under investigation and Lozman now lives with his girlfriend at an undisclosed location.

Despite the setback, in November Lozman won yet another case, this one forcing the City of Riviera Beach to give him street addresses for his properties, enabling him to obtain permits from the city, state, and Army Corps of Engineers.

Lozman has since changed his mind about creating a community of floating homes in Riviera Beach. Instead he wants to create Tidal House at Renegade, a development of 40 or 50 twostory stilt homes that use a pinion gear system to move with the tides, plus aerodynamic roofs that can withstand high winds.

Terry and Terry Architects, a San Francisco firm run by brothers Alex and Ivan Terry, came up with the design that, Alex Terry tells the BT, was unveiled at an architecture exhibit in Venice, Italy, last summer and is based on exploratory oil rigs.

“They’re kind of a response to changing climate and a lot of issues with tidal action…and places where there is severe storm action,” Alex Terry says, adding that the Tidal House design has also garnered interest in India.

“The stilt home is a superior solution,” says Lozman, who has hired contractor Donna Milo, a former Upper Eastside resident (and onetime Miami City Commission candidate) to build the homes. Lozman hopes to start construction by 2018, adding that he’s already had offers to buy Tidal House residences for $3 million each.

“In Palm Beach County, three million is not a lot of money,” he notes, pointing out that the condos on Singer Island sell for as much as $10 million.

Wayne Pathman is an environmental and landuse attorney. He has served on special committees on sea level rise for the City of Miami and MiamiDade County, and is chairman of the Miami Beach Chamber of Commerce.

Pathman advocates for extensive changes in urban codes and infrastructure improvements to address the threat of rising seas. He supports actions spearheaded by Miami Beach Mayor Philip Levine namely, adding pumps and elevating streets to handle flooding.

Pathman has advocated against creating new historic districts in the city’s North Beach neighborhood, arguing that doing so would limit options for property owners in the future, as tidal events become more pronounced. Pathman often reminds people that the insurance industry is already looking at the future impacts of sea level rise in Florida.

But placing floating homes and stilt houses on South Florida’s waterways? “I don’t think people here in South Florida are really ready for floating homes like other parts of the world,” he says. “It has to be explored when sea level rise becomes more of an impact.”

Miami Beach, in particular, has been pretty tough on even common boats anchoring on the city’s waterways, this in response to waterfront homeowners who complain that liveaboards (full time boat residents) invade their privacy. Although a proposed law making it illegal to live aboard a boat fulltime was rejected in 2002, the city has recently passed laws forbidding vessels from anchoring in public waters without permission, except for specified areas near the Venetian Causeway.

Dutch architect Olthuis emphasizes that Maule Lake has been privately owned for decades, and he is sure the Amillarah project would be beneficial to the surrounding neighborhoods and the city itself. He points out that the Supreme Court ruling in Lozman’s case clarifies that floating homes without motors are actually homesteads that can be taxed as property. In other words, floating homes can provide cities with revenues.

Olthuis argues that places like South Florida need to start thinking seriously about how climate change will affect living choices.

“You can see that cities like Miami and New York and Guangzhou are the top cities being threatened by sea level rise, in terms of assets,” he says. “Miami has to come up with different kinds of solutions. You have to come up with new technology, and you have to change the DNA of cities. You have to slowly start implementing these kinds of developments that have growing resiliency.”

He’s hopeful that building codes in Florida will soon force developers to build in preparation for a changing environment, much like in his native Netherlands. “In 10 or 15 years, builders will, for the most part, have made the switch to resilient typologies like floating houses or stilt houses in Miami,” he predicts.

Other aspiring builders, like Doug Pope in Jacksonville, think the new administration in Washington will be their ally in removing regulations. A single regulation dealing with Oceana’s water treatment stood in the project’s way when it was proposed in 2010, Pope asserts. Then the project fell into limbo when Oceana’s financial backers suddenly balked. Now he is somewhat confident he can find new investors to raise the $26 million needed to build Oceana.

“Things are looking better,” he says. “I wouldn’t say ‘good.’ I would say better.” But why submit yourself to outside governmental regulations at all? Joe Quirk, a science author affiliated with Peter Thiel’s Seasteading Institute, says technology can innovate more quickly if entrepreneurs don’t have to report to government. That’s why the Seasteading Institute wants to create floatingisland “startup societies” with their own autonomy.

If the French Polynesia pilot project succeeds, notes Randolph Hencken, the institute’s executive director, he can envision “future seasteads in places like Miami and Bangladesh.” Says Quirk: “In order for us to bring this technology to Florida or Miami, the governments of Florida and Miami would have to legislate us some measure of legislative or regulatory autonomy.”

Absent new discoveries that could clean the atmosphere of greenhouse gases, the oceans will continue to warm and rise increasingly faster as ice from Greenland and Antarctica slips beneath the waves, predicts Harold Wanless, chairman of the University of Miami’s Department of Geology and an outspoken climatologist.

Because humans have been burning fossil fuels for more than a century, Wanless points out, the planet has about as much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere today as it did 3 million years ago, a time when there were no polar ice caps and the oceans were 80 feet higher. “This isn’t a cloud of smoke that will just evaporate,” Wanless quips.

The UM professor adds that we won’t have to wait until 2100 to see the full effects of sea level rise. In less than 30 years, he says, tidal flooding will be significantly worse for lowlying areas like Broward, Miami Beach, Key Biscayne, west MiamiDade, south Brickell, and Miami’s Edgewater and Upper Eastside neighborhoods, along with other areas up and down the Biscayne Corridor. (For more on sea level rise projections, see “Six Feet Under,” June 2015.) According to Wanless, Miami Beach’s expensive efforts to mitigate rising seas will only last a couple of decades.

Wanless says the innovations proposed by Olthuis, the Terry brothers, and the Seasteaders are “nice” and “creative,” but he questions if anyone is going to want to live in a flooded area that will be significantly hotter, ravaged by more powerful storms, and difficult to traverse.

A better idea, Wanless suggests, would be preparing places like Omaha, Nebraska, to accommodate the millions of people who will be displaced from coastal communities in the United States.

Olthuis, however, is undeterred. He’s confident his floatingstructure designs can help South Florida adapt to the changes that most scientists agree are certain to come. And in addition to Maule Lake, he has leads on other sites.

“You can imagine that other people with new opportunities have contacted us,” he says. “Developers who are asking if we can do the same for their water.” Olthuis wouldn’t identify those developers or where future floating projects might be located.

“They’re not ready,” he explains. “They must get hold of all their licenses and all their agreements before they start bringing their projects into the open.”

Interview of the The New York Times with Koen Olthuis

CHRISTOPHER F. SCHUETZE NOV. 28, 2016

A Dutch Architect Offshores the Future of Housing

Floating houses in Amsterdam designed by Koen Olthuis. Mr. Olthuis’s architectural firm, Waterstudio, which he founded in 2003, has completed more than 200 floating homes and offices. CreditFriso Spoelstra/Waterstudio.nl

RIJSWIJK, The Netherlands — Early next year when a converted cargo container on a floating foundation of plastic bottles opens on the flood-prone shores of Korail Bosti, Bangladesh’s largest slum, few of its users are likely to celebrate the 320-square-foot space as a revolution. Yet, according to Koen Olthuis, the lead architect on the project, it is part of the greatest transformation in urbanism since Elisha Otis built the safety brake that gave rise to the modern elevator, skyscrapers and ultimately urban density.

“It will change the DNA of cities,” Mr. Olthuis said of the technology at the heart of his designs in an interview in his studio, a converted supermarket in this suburb of The Hague that also serves as his business headquarters.

In an era when the needs of growing urban centers are changing rapidly and rising sea levels threaten waterside construction, Mr. Olthuis has been busy working on a solution: the floating building.

Mr. Olthuis founded Waterstudio — which he describes as the first modern architecture firm to exclusively build floating houses — in 2003. More than a decade on, he and his team consider themselves pioneers in a growing movement. The firm has completed more than 200 floating homes and offices, many of them in the Netherlands, where several floating neighborhoods have sprung up in the last decade.

The team’s designs have gone global, with showcases ranging from exclusive floating islands in Dubai and the Maldives for the superrich, to more modest designer homes in Europe and the United States, to projects like the floating container, called City App, that will serve as an education center in the poorest neighborhoods in Asia.

A rendering of a floating private island that can be moved around to suit the owner’s desires.CreditWaterstudio.nl and Amillarah Private Islands

Mr. Olthuis was a candidate for Time Magazine’s list of the 100 most influential people in 2007, and he has been described as a visionary in the media. The BBC dubbed him the “Floating Dutchman” when featuring his plan to build a floating block in Naaldwijk, the Netherlands.

“He was really one of the first architects who saw that building on water could develop a whole new design language,” said Tracy Metz, an American journalist based in the Netherlands and a co-author of “Sweet & Salt: Water and the Dutch” (2012).

Although live-aboard boats and then houseboats have existed for centuries, the modern floating house is a relatively recent invention, with new materials and methods allowing for full-height construction without the loss of stability or the risk of intruding moisture.

The buildings are constructed on a floating foundation (sometimes stabilized by fixed stilts), which makes them flood-proof, affordable and independent of expensive real estate, although obtaining building permits can be tricky.

Perhaps most important for the slums of Dhaka, the units — which can house amenities like internet terminals, toilets and showers, large-scale water filtration, medical clinics, community kitchens and workshops — can be moved easily to where they are needed most.

Koen Olthuis CreditWaterstudio.nl

“If I were to build only floating islands for the wealthy, I would only make 150 happy people in the next 20 years,” said Mr. Olthuis, 45, who is the grandson of both an architect and a shipbuilder. “If we use this technology also to upgrade slums, we can change the lives of millions.”

As for most of Waterstudio’s other clients, the top draws are the crisp, elegant and open designs, the water views, and — for those with pockets deep enough — the optional private beaches.

The first units of his high-end Oceana project in Dubai are to be delivered next summer. For the project, Mr. Olthuis and Dutch Docklands, the development firm he co-owns, are designing and building 33 islands of 11,000 square feet that support custom-built villas of up to 5,500 square feet each, at an estimated total project cost of $170 million.

The villas themselves resemble smaller houses he has designed in the Netherlands. With open spaces and barely-there transitions between the indoors and the outdoors, his designs are airy, light and modern. The undersides of the islands are equipped with anchor points for marine life that resemble holds on artificial climbing walls, leading to a collaboration with Ocean Futures Society, established by Jean-Michel Cousteau, the son of the explorer Jacques Cousteau.

Christie’s real estate, which is acting as a broker for the units, notes that they can be transported around the globe. Depending on the level of customization and enhancements, the islands will sell for an estimated $5 million.

A rendering of City App, a floating cargo container that can be used to deliver essential services to areas in crisis. CreditWaterstudio.nl

For those on a tighter budget, Mr. Olthuis is set to help reconvert on-the-water living spaces in Weehawken, N.J., just south of the Lincoln Tunnel, on the Hudson River. The first phase of the project focuses on “livable yachts,” which are scheduled to go on the market late next year for slightly less than nearby condos, according to Steve Israel, the developer.

In Bangladesh, the City App aims to bring services to the most affected areas of a large and flood-prone slum. It is the first time Mr. Olthuis has brought his ideas to bear in development work and is almost entirely funded by a foundation he set up that receives funding from Dutch partners.

The floating structure that will pioneer the program was built this year in a yard in Helmond in the south of the Netherlands, nearly 5,000 miles from Dhaka, and features two rows of computers and benches. Four other models are now being built to bring other urgently needed services to Dhaka, although none of the units will consist of actual dwellings.

While he is mostly known in design circles for his open glass constructions, Mr. Olthuis sees a broader mission. He is also an academic member of the flood resilience group at Unesco-IHE in Delft, a water research institute.

In his version of the future, cities will make better use of their water surfaces. In some cases, they will have no choice. Mr. Olthuis envisions public buildings like schools, stadiums and even parks being moved to different waterside neighborhoods according to need.

“In 20 years,” he said, “cities are going to be different than today.”

Buoyant buildings: better than boats?

By P.Kennedy

Suffolk Construction’s Content

Build smart

September.16.2016

With hurricane season at its peak, we explore how floating homes might help us adapt to bigger storms and rising seas.

The Dutch have a head start when it comes to dealing with water. The extreme weather events and rising sea level that scientists predict this century will affect millions around the globe—most of the world’s largest cities are along the coasts. But that problem has long been acute in the low-lying Netherlands, where two-thirds of the population live in flood-prone areas. Over the centuries, the Dutch have honed technologies—dikes, canals, and pumps—that keep their streets and houses dry.

Now, a new generation of Dutch engineers and architects is modeling another method. Rather than fight to keep water out, they say, why not live on it? The basic idea is not new—hundreds of free spirits live on traditional houseboats in quirky communities like Sausalito, California, and Key West, Florida. But in the Netherlands over the past few years, novel technologies have allowed developers to build roughly a thousand (and counting) stable, flat-bottomed, multi-story homes connected to land-based utilities yet designed to rise and fall with the tides and even floods. House boats, these ain’t.

And this is just the start. The Dutch are thinking bigger, and they’re exporting their floating-home vision worldwide, betting that the rest of us coastal clingers could use it. Some projects exist already, others are on the drawing board or coming soon. Let’s take a look at a few, from the workaday to the fantastical, and from overseas to right here in the States.

A “normal house” on water

The first of its kind, Waterbuurt (above and top) is a planned neighborhood of about 100 (eventually 165) floating houses in Amsterdam’s IJmeer Lake, part of a freshwater reservoir dammed off from the North Sea in the 1930s. Waterbuurt broke ground—er, water—in 2009, and was largely complete by 2014. Connected by jetties, the structures are three-story, 2,960-square-foot houses built of wood, aluminum, and glass.

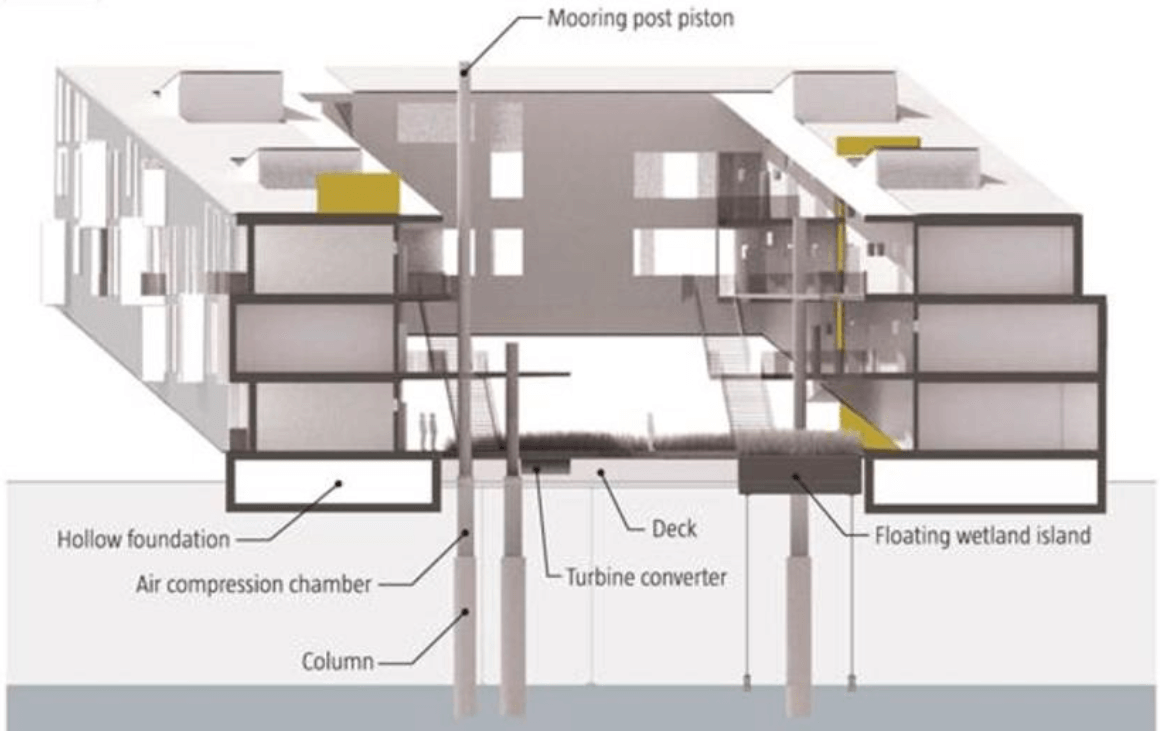

And the foundations? Floating concrete tubs. Each house is designed to weigh 110 tons and displace 110 tons of water, which—as Archimedes could tell you—causes it to float. (The bottom floor is half submerged.) To prevent rocking in the waves, the house is fastened to two mooring posts—on diagonally opposite corners of the house—driven 20 feet into the lake bed. The posts are telescoping, allowing the house to rise and fall with the water level. Flexible pipes deliver electricity and plumbing.

Because any crack in the foundation tub could cause the house to sink, there can’t be any joints; builders pour the entire basement in one shot—much like the parking garage of the Jade Signaturecondo complex in Florida. In a facility 30 miles away from the IJmeer Lake site, crews use special buckets that pour 200 gallons per minute to finish all four walls and the floor in a single shift.

Just four months elapse before the entire house is built; then it’s towed by tugboat—30 miles through canals and locks—to the plot. The transportation is a major reason the houses cost about 10 percent more than an average home in Amsterdam, though they’re still aimed at the city’s middle class. The houses were designed by architect Marlies Rohmer, for developer Ontwikkelingscombinatie Waterbuurt West.

Photo by Marcel van der Berg

Photo by Marcel van der Berg

Once secured to its mooring posts, the structure is formally considered an immovable home, not a house boat. (Although owners have the option of naming their waterborne homes as sea captains do. One couple calls theirs La Scalota Grigia—Italian for “The Grey Box.”)

With high ceilings and straight angles, a house in Waterbuurt “feels like a normal house,” wrote a New York Times reporter who toured one. But some residents say they do feel their home swaying when the wind kicks up.

One other drawback, or at least challenge: Residents have to decide before the house is even built where they’re going to place furniture, because that will affect its balance. The walls are built to varying thickness, depending on the layout submitted. What if you inherit a beloved aunt’s piano after you move in? Or have another child and need to buy a bunkbed? To compensate, homeowners can install balance tanks on the exterior or Styrofoam in the cellar, or carefully move furniture around or even deploy sand bags. A bit of a hassle, but perhaps with an eye on rising sea levels, that’s a risk Amsterdammers are willing to take.

Rendering courtesy of architect Koen Olthuis, Waterstudio.NL, and developer Dutch Docklands

Living large on a lake

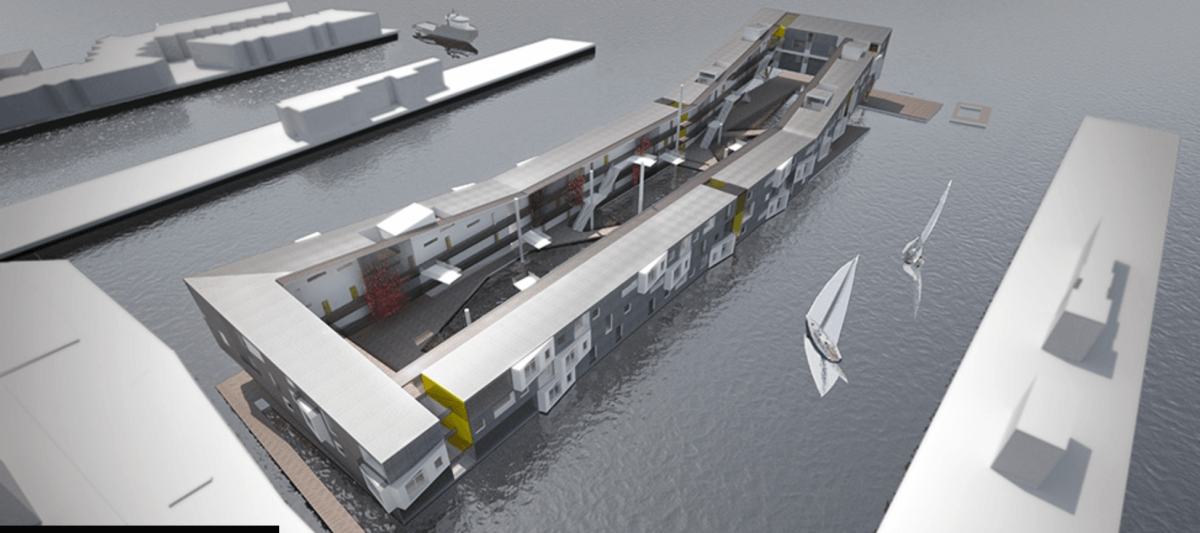

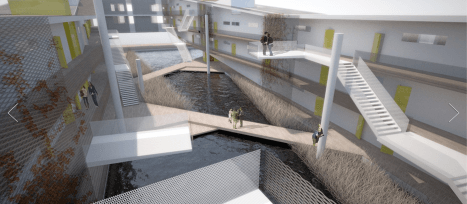

At the luxury end of the market, there’s Citadel, which aims to be the world’s first floating apartment complex. Construction began in 2014. Citadel uses the same technology as Waterbuurt—floating concrete base, mooring pistons—but on a larger scale, in the sense that this will be one massive deck supporting a multifaceted apartment building, rather than a place for many individual houses to dock. Think of it as Waterbuurt with butlers. (And underwater parking and other amenities).

Citadel was designed by pioneering architect Koen Olthuis’ Waterstudio in partnership with master developer Dutch Docklands. The concrete caisson foundation will measure 240 by 420 by 9 feet, supporting 60 sleek, aluminum-clad apartments in an irregular arrangement that from the air will look a bit like a scattering of stacks of jigsaw puzzle pieces. Palm trees will sprout from courtyards. Green roofs are planned, and the developer hopes to have Citadel use 25 percent less energy than a similarly-sized complex on land.

One thing remarkable about Citadel is the body of water it will float in: a lake that doesn’t exist yet, though it did once. Construction is taking place in a polder, one of the Netherlands’ many low-lying areas that is only dry because pumps work 24-7 to keep the water out. Once construction is complete, the pumps will shut off, and the area will be re-flooded, to 12 feet deep. Eventually, Dutch Docklands plans to build five more complexes in the same un-manmade lake, dubbed New Water.

Rendering courtesy of architect Koen Olthuis, Waterstudio.NL, and developer Dutch Docklands

Exporting the vision

This is all well and good for the Dutch, but what about the flat, flood-prone coastal regions here in the USA? Like, for example, Florida? Well, the Dutch have thought of that. Another Waterstudio-Docklands project is Amillarah Floating Private Islands Miami, located in Maule Lake. A former limestone rock quarry, the privately owned lake is an inlet a mile and a half from the ocean, a bit north of Miami Beach.

Dubbed a “villa flotilla” by the Miami Herald, the complex will consist of 29 6,000-square-foot condos priced at $12.5 million each. As with Citadel and other Dutch Docklands projects, there are plans to boost the Maule Lake project’s sustainability, in this case with solar and hydrogen-powered generators.

Though similar to Citadel in the Netherlands, this project wouldn’t have been possible Stateside without a 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision that floating homes could be considered real estate, not boats. As the Herald explained, would-be buyers of Amillarah condos can get a mortgage and homeowners’ insurance, and the Coast Guard can’t bust in and inspect for life jackets.

Maule Lake will be out of reach for most Floridians financially, but if the ambitious project succeeds, it will provide visual evidence to Miami that floating houses can be done, and perhaps inspire larger, more modest developments like Amsterdam’s Waterbuurt.

Renderings courtesy of architect Brian Healy

Not hidebound in the Hub

In Boston, architect Brian Healy, for the local office of Perkins+Will, won awards in 2013 for his design of Floatyard, a proposed apartment complex that would stretch out onto the Mystic River from the Charlestown Navy Yard, using much of the same technology as the abovementioned Dutch initiatives. Were Floatyard and similar projects to become reality here, Healy argues that they would not only help the city adapt to rising seas but also revitalize disused shipyards (for example, in East Boston and Quincy) and reorient Boston—historically a seaport—toward its natural center, the harbor.

What makes Floatyard unique is its central courtyard: a floating wetland island, built above the foundation, to be seeded with native marsh grass and aquatic wildlife. The design also includes a plan to harvest tidal energy via the structure’s mooring post pistons.

Elder statesman of architecture criticism Robert Campbell could have been talking about any of the above floating buildings when he wrote of Floatyard: “Like a lot of good ideas, this one is just crazy enough to make sense.” Given the prediction for the ocean to rise between three and five feet by the year 2100, it might be more crazy not to build on floating tubs.

Olthuis: ‘Bouw amfibische wijken in overstromingsgebieden’

By Architectenweb

September.5.2016

Over de hele wereld ontwerpt hij drijvende gebouwen, zelfs hele drijvende wijken; architect Koen Olthuis van Waterstudio.NL. Op donderdag 15 september geeft hij op Architect@Work een lezing over de mogelijkheden van drijvende steden. Architectenweb hield met de architect een voorgesprek.

“De steden die we al eeuwenlang op het land bouwen volgen ook maar een concept”, begint architect Koen Olthuis van Waterstudio.NL. “Het is een bewezen concept, maar ook een die niet optimaal functioneert. Onze boodschap is: kijk ook eens naar water en welke mogelijkheden dat biedt om tot een andere stedenbouw te komen.”

Water biedt de stad in Olthuis’ optiek veiligheid, ruimte en flexibiliteit. Om met dat laatste aspect te beginnen: met de verplaatsbaarheid van drijvende gebouwen kunnen steden veel minder statisch worden. De tijd die steden nodig hebben om te reageren op veranderende sociaal-economische vragen, de response time zoals Olthuis het noemt, kan dan flink omlaag.

Als voorbeeld noemt Olthuis steden die enkel in een bepaald seizoen gebruikt worden, seasonal cities. Kunnen die gebouwen off-season niet op een andere plek ingezet worden? “Laat steden met het gebruik meebewegen”, benadrukt Olthuis.

Dat sommige steden dicht bebouwd zijn, betekent volgens hem nog niet dat ze ten volle gebruikt worden. “Ik noem dat de efficiency van het gebruik.” Sommige functies kunnen op het water – als verplaatsbaar gebouw – intensiever gebruikt worden dan wanneer ze op het land zouden blijven.

In Libanon werkt de architect momenteel aan een drijvende woning die uit twee U-vormen bestaat. Hierbij heeft de buitenzijde van de U-vorm een gesloten gevel en de binnenzijde een open gevel. De toekomstige bewoners kunnen straks met beide bouwdelen spelen en ervoor kiezen om de woning volledig gesloten te houden, deze deels te openen, of deze helemaal te openen. Zo kunnen de bewoners bijvoorbeeld inspelen het veranderende klimaat door het jaar heen. Van volledig gesloten naar volledig geopend kost volgens Olthuis maar een paar uur tijd.

Amfibische steden

Wat betreft waterveiligheid vindt Olthuis het interessant wat momenteel in steden als Bangkok, Tokyo en Shanghai gebeurt. Het water heeft daar meer ruimte nodig. Daarom zijn er veiligheidszones ingesteld die nog niet ontwikkeld kunnen worden. Omdat ze bijvoorbeeld eens in de zoveel tijd onder water lopen. “Amfibische wijken of steden kunnen daar een uitkomst zijn.”

Een permanent drijvende woning biedt niet voor iedereen het gewenste comfort, geeft Olthuis toe. De meeste mensen wonen toch het liefst aan een straat met een eigen tuin. Een woning die normaal gesproken op de grond staat, maar bij een overstroming bijvoorbeeld eens in de vijf jaar korte tijd drijft, kan dan een uitkomst zijn.

“De grootste bedreiging in Nederland komt niet van de stijgende zeespiegel, maar van hoge waterstanden in de rivieren en hevige regenval”, stelt Olthuis. “Een aantal van de meer dan 3.500 polders in ons land zouden we daarom in moeten richten als noodopslag voor water. Hier kunnen vervolgens amfibische wijken gerealiseerd worden.” In China en Thailand werkt Olthuis al aan plannen voor dergelijke wijken.

Kansen in Nederland nog onbenut

Ondanks dit alles is het in Nederland de afgelopen jaren opvallend stil rond het bouwen op water. In Rotterdam wordt een drijvende boerderij gebouwd, in Amsterdam worden enkele tientallen waterkavels op de markt gebracht voor particuliere woningbouw. “Onder de 70.000 woningen die jaarlijks in Nederland gebouwd worden zijn misschien honderd waterwoningen.”

“Nederlandse ontwikkelaars zijn lui”, constateert Olthuis. “Nederland is op dit punt gewoon meer een innovatieland dan een uitvoerland.” De hele wereld bekijkend is de architect echter zeer optimistisch over drijvende architectuur. Overal is daar grote interesse in.

Richting architecten heeft Olthuis ook een boodschap: “Zie water als een extra ingrediënt in de stedenbouw dat veiligheid, ruimte en flexibiliteit biedt.”

Architect@Work vindt plaats op woensdag 14 september en donderdag 15 september in Rotterdam Ahoy. Als mediapartner heeft Architectenweb rond het thema architectuur en water een gevarieerd lezingenprogramma samengesteld. Binnen dit programma geeft architect Koen Olthuis van Waterstudio.NL op donderdag 15 september om 17:30u een lezing met de lengte van een uur.

De lezingen tijdens Architect@Work zijn gratis bij te wonen. Registreer je wel van tevoren even. Ga naar www.architectatwork.nl, klik op de knop Gratis Bezoekersregistratie en registreer je met de code 455.

Het conflict van de dynamische mens met statische steden en gebouwen

By Tanny de Nooy

Blandlord

July.1.2016

1 Juli 2016 Blandlord

Vastgoed móet flexibiliteit gaan bieden

Koen Olthuis studeerde Architectuur en Industrieel Ontwerp aan de TU Delft. Hij werkt sindsdien als architect en heeft water als specialisme. In 2007 noemde Time Magazine hem in de lijst ‘most influential people’ vanwege zijn werk in het wereldwijd groeiende interesseveld waterontwikkeling. Het Franse tijdschrift Terra Eco verkoos hem in 2011 tot een van de honderd ‘groene’ mensen die de wereld zullen veranderen. Olthuis’ architectenbureau Waterstudio en is gevestigd in Rijswijk.

“In Nederland kennen we als geen ander de mogelijkheid om van water bouwgrond te maken. We hebben een lange historie als het gaat om het bewoonbaar maken van natte gebieden. Dat fascineert me al sinds ik studeerde.” Koen Olthuis houdt zich al vijftien jaar bezig met architectuur op het water. In 2003 richtte hij Architectenbureau Waterstudio op en sindsdien is het bureau alleen maar gegroeid. Olthuis is een veelgevraagd architect, van China en Dubai tot aan de Oekraïne en de Malediven.

Olthuis is overtuigd van de vele kansen die water te bieden heeft als het gaat om te toekomst van vastgoed. “Waar het water vroeger nog benaderd werd als een vijand die in toom gehouden moest worden, is het de afgelopen twintig jaar een vriend geworden, die ongekende mogelijkheden biedt: we kunnen met z’n allen op het water gaan wonen! En ja: dat kan overal ter wereld. Van woonboten en waterwoningen tot drijvende resorts: als er water is, kun je erop bouwen.”

“Ik weet zeker dat de vastgoedwereld de komende jaren enorm gaat veranderen”, zegt Olthuis. “Kijk om je heen; de wereld is vandaag écht anders georganiseerd dan tien jaar geleden en dit is nog maar het begin! Bedrijven veranderen de manier waarop ze werken onder invloed van de mogelijkheden van internet en nieuwe technologieën en ook in onze privélevens veranderen onze behoeften onder invloed van deze ontwikkelingen. Je kunt op je vingers natellen dat wat wij verwachten van de fysieke ruimtes waarin we wonen en werken óók zal veranderen.”

De wereld om ons heen verandert

Olthuis wijst op de grote leegstand van kantoorgebouwen die zich het afgelopen decennium in veel steden ontwikkeld heeft. Hij verklaart die leegstand door de luiheid en traagheid van de vastgoedwereld. “Onze steden zijn statisch, onze gebouwen zijn statisch, maar wij, de mensen die er gebruik van maken zijn dynamisch. Je kunt de prachtigste gebouwen maken, maar omdat de wereld om ons heen zo snel verandert is dat gebouw over tien jaar al achterhaald. Als we op deze manier blijven werken zal er niets veranderen. Gebouwen die we nu ontwerpen zullen niet meer voldoen aan de dan geldende wensen en behoeften als ze gerealiseerd zijn. Vastgoed zal meer flexibiliteit moeten gaan bieden.”

“Er zijn zoveel veranderingen dat je die als architect onmogelijk allemaal kunt voorzien”, stelt Olthuis nuchter vast. “En dus is flexibiliteit bieden het enige wat je kunt doen. Vastgoed zou niet statisch moeten zijn. Vastgoed evolueert. Nu bouwen we gebouwen die zo lang staan dat ze overbodig worden en een negatief effect op steden hebben. Architecten moeten gaan ontwerpen voor verandering. We moeten gebouwen ontwerpen die snel en eenvoudig aanpasbaar zijn, zodat ze mee kunnen golven met onze veranderende wensen.” Dat meegolven mag je van Olthuis vrij letterlijk nemen: “Alles wat je op water bouwt is makkelijk aanpasbaar. Je kunt elementen snel verbinden met elkaar en je kunt andere dingen wegschuiven. Maar ook kartonbouw en panden die bestaan uit een lichte houtstructuur, piepschuim of containers zijn oplossingen die veel meer passen bij de wensen en behoeften van deze tijd. Nog geen twintig jaar geleden spuugden we erop, maar nu zien we de logica ervan in. Het biedt precies díe flexibiliteit die de vastgoedsector nodig heeft.”

Flexibiliteit is de sleutel

En flexibiliteit is ook precies wat bouwen op het water te bieden heeft, weet Olthuis. Als het aan hem ligt bouwen we over tien jaar hele steden op het water zoals dat in andere landen al lang gebeurt. “Denk bijvoorbeeld aan de RAI in Amsterdam. In feite is dat een ontzettend log gebouw, dat voor veel events die er worden georganiseerd nét te klein of veel te groot is. Ik kan me voorstellen dat je zegt: ‘we slopen de RAI en bouwen woningen op die gewilde plaats in de stad’. Met het geld dat dat oplevert zouden er drijvende expositieruimtes in de Amsterdamse havens gebouwd kunnen worden. Daar is immers plek zat! Bij een groot event laat je die nieuwe ruimtes naar een plek in hartje centrum drijven. Op die manier benut je de ruimte die je ook echt nodig hebt.” Olthuis droomt van een dynamische stad met flexibele gebouwen.“De ziel van zo’n stad wordt bepaald door vaste iconische gebouwen als kerken en universiteiten. Maar daaromheen bouwen we flexibele en verplaatsbare functies die gedurende hun levensduur niet meer perse locatiegebonden zijn. Helemaal ingespeeld op wat de gebruiker van het gebouw op dat moment nodig heeft.”

Het aantrekken van de economie en daarmee de woningmarkt is voor Olthuis hét moment om op te roepen tot meer innovatie in de vastgoedsector. “Juist nu het weer beter gaat moeten we in durven zetten op verandering. Als we blijven doen wat we altijd al deden zullen we vroeg of laat weer tegen dezelfde problemen aanlopen. Als we met behulp van de nieuwe technologieën die we nu voorhanden hebben durven te werken, plukken we daar al heel snel de vruchten van.” De kern van Olthuis’ verhaal? “Denk na over hoe we kunnen bouwen voor ‘change’. Wat er over 10 jaar gaat gebeuren weten we niet. Bouw dus met een kortere levensduur. Van nieuwe, slimme manieren van investeren en financieren tot het durven gebruiken van nieuwe bouwmaterialen: gebouwen moeten weer van en voor de mensen zijn. Dát is de toekomst.”

These next-level underwater villas are making waves

By Kate Springer

CNN

July.11.2016

Citadel, Westland

An ambitious project from Dutch developers ONW/BNG GO, the Citadel is Europe’s first floating apartment building. It’s part of the New Water development project, which will comprise six floating apartment buildings — all designed to adapt to flooding and rising water levels.