Bouwen op water, waarom niet?

Mondiaal Nieuws, RENÉE DEKKER

Bouwen op water, waarom niet?

Steden worden wereldwijd steeds voller vanwege de trek naar de stad. Koen Olthuis, architect, had een eenvoudige maar revolutionaire ingeving om het gebrek aan ruimte aan te pakken: ‘Waarom niet bouwen op water?’ Speciale drijvende funderingen stelden Olthuis in staat om dit te realiseren. MO* sprak met de Nederlander over hoe bouwen op water ook kansarmen in het Zuiden ten goede kan komen.

Koen Olthuis, eigenaar van het architectenbureau Waterstudio, werd omwille van zijn FLOAT!-project door Time Magazine opgenomen in de lijst “Most influential people 2007”. Het Franse tijdschrift Terra Eco stelde in 2011 dat Olthuis één van de honderd “groene personen” is waarvan de wereld nog veel mag verwachten. Zijn passie voor drijvend bouwen leverde Olthuis ook de bijnaam “Floating Dutchman” op.

Steden zijn niet vol

Olthuis over zijn eigen idee: ‘Als architect kreeg ik regelmatig te horen dat de steden vol zijn. Daarom moet ik in steden zoals New York eerst op zoek gaan naar een pand dat gesloopt kan worden, pas dan kan de bouw van een nieuw project starten. Zo zijn we al snel drie jaar verder voordat een nieuw gebouw af is. Soms zijn de behoeftes van de stad dan al veranderd, met als gevolg dat gebouwen sneller hun houdbaarheidsdatum passeren en opnieuw gesloopt zullen worden.’ Voor dit probleem wilde Olthuis een oplossing zoeken.

De inspiratie hiervoor vond Olthuis niet ver van huis: in het dichtbevolkte Nederland is jaren aan landwinning gedaan om de bebouwbare grond uit te breiden. ‘Toch werkt dit systeem niet optimaal. Omdat een groot deel van Nederland onder de zeespiegel ligt, moet er dag in dag uit gepompt worden om het land droog te houden.’

Gewone huizen bouwen op water, het kan!

Zo kwam Olthuis op het idee om op water te bouwen. ‘Dit bestaat natuurlijk al in de vorm van woonboten. Maar dit voldoet niet aan de eisen van de meeste consumenten van vandaag. Daarom wilde ik gewone gebouwen en huizen kunnen bouwen op water.’ Hiervoor gebruikt Waterstudio een speciaal soort drijvende fundering, die zeer stabiel en veilig is. ‘Doordat negentig procent van alle grote steden op aarde in de buurt van water liggen, creëert dit heel veel nieuwe bouwruimte.’

‘We moeten ook af van het idee dat gebouwen statisch zijn.’ Olthuis verwijst naar de Olympische Spelen: ‘Daarvoor wordt er iedere vier jaar een volledige stad uit de grond gestampt, maar na afloop worden die gebouwen vaak nauwelijks meer gebruikt. Zou het niet beter zijn als we eenmalig drijvende stadions en andere gebouwen konden bouwen om die vervolgens iedere vier jaar over water te verplaatsen naar een andere stad?’

Steden als smart phones

Olthuis’ project City Apps speelt hierop in. Het project ziet steden als smart phones: ze zien er aan de buitenkant allemaal ongeveer hetzelfde uit, maar toch heeft iedereen er andere applicaties op staan. ‘Zo is het ook met steden: iedere stad heeft andere behoeftes. Door drijvend te bouwen, kan men de stad constant aanpassen aan de noden, simpelweg door gebouwen te verslepen naar een andere plaats binnen de stad of zelfs een andere stad.’ Drijvend bouwen is daarom ook duurzamer: gebouwen die anders gesloopt zouden worden, kunnen een tweede leven krijgen op een andere plaats.

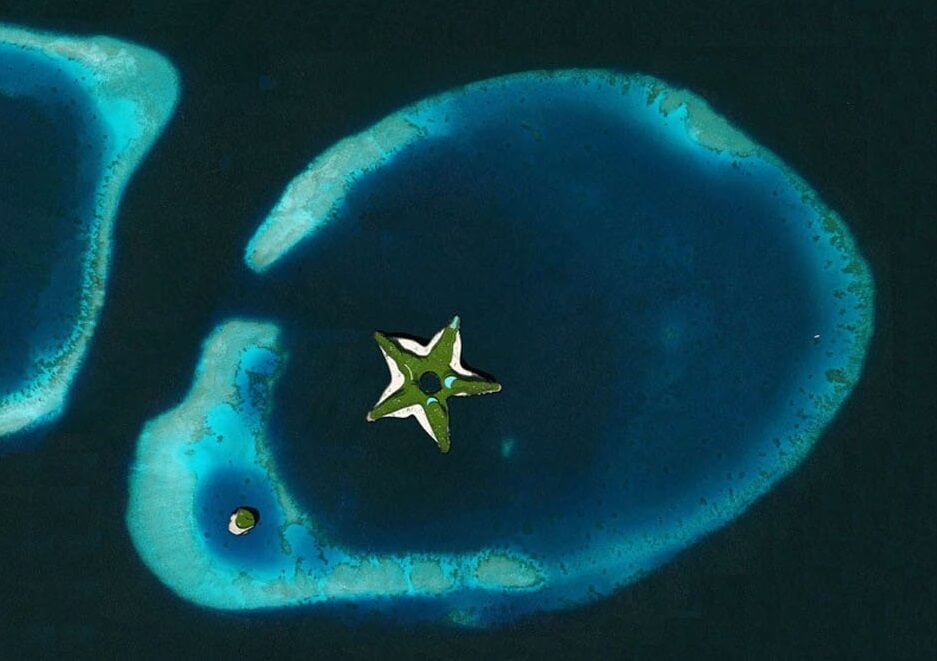

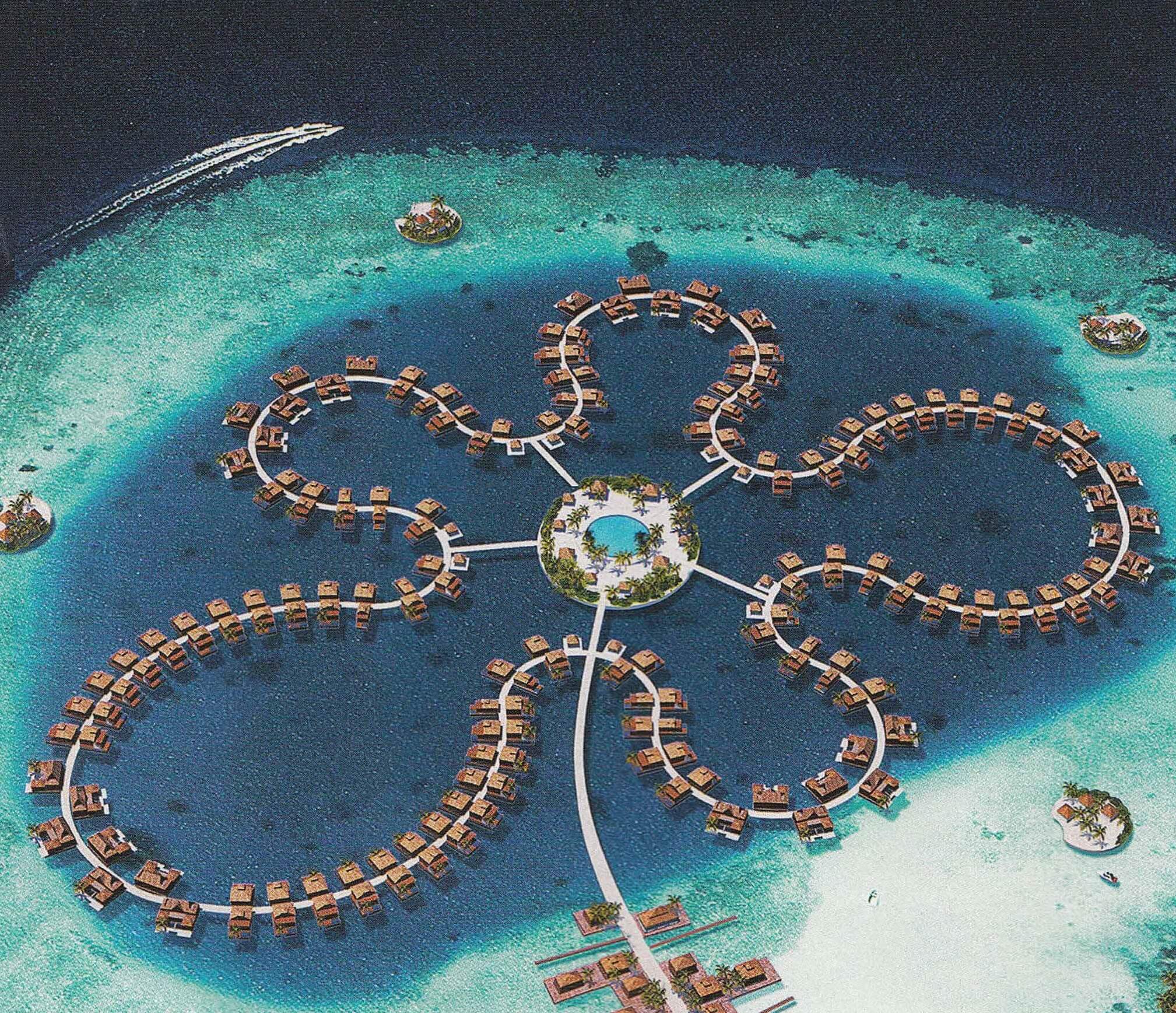

Bouwen op water is inmiddels geen toekomstmuziek meer: op dit moment lopen er drijvende bouwprojecten van Waterstudio in Miami, de Malediven en Saoedi-Arabië. Het gaat onder andere om moskeeën en luxehotels. ‘Maar mijn bedoeling met dit project was dat ook juist de armen in het Zuiden ervan zouden kunnen profiteren. Neem nu sloppenwijken, die liggen bijna altijd in gebieden nabij water, omdat niemand anders het aandurfde daar te bouwen.’

Sloppenwijken geen tijdelijk fenomeen

‘Velen gaan er van uit dat sloppenwijken tijdelijk zijn, maar dat is een misverstand. Veel sloppenwijken zijn niet erkend door de overheid, maar toch blijven ze bestaan en groeien ze zelfs. Steeds meer overheden zijn zich hiervan bewust. Ze zijn sneller geneigd om een sloppenwijk een reguliere status te verlenen wanneer er voorzieningen aanwezig zijn. Vaak ontbreken deze totaal, waardoor de wijken een onzekere status behouden’.

En juist in deze behoefte naar voorzieningen kan Olthuis’ City Apps-project voorzien: zo ontwikkelde hij drijvende sanitairblokken, zonnecollectoren, waterreinigingsinstallaties en wasruimtes, speciaal voor sloppenwijken. Op dit moment lopen er twee projecten in het Zuiden: een in de Thaise hoofdstad Bangkok en een in de Bengaalse hoofdstad Dhaka. Beide steden liggen aan het water en worden regelmatig getroffen door overstromingen.

Drijvend sanitair

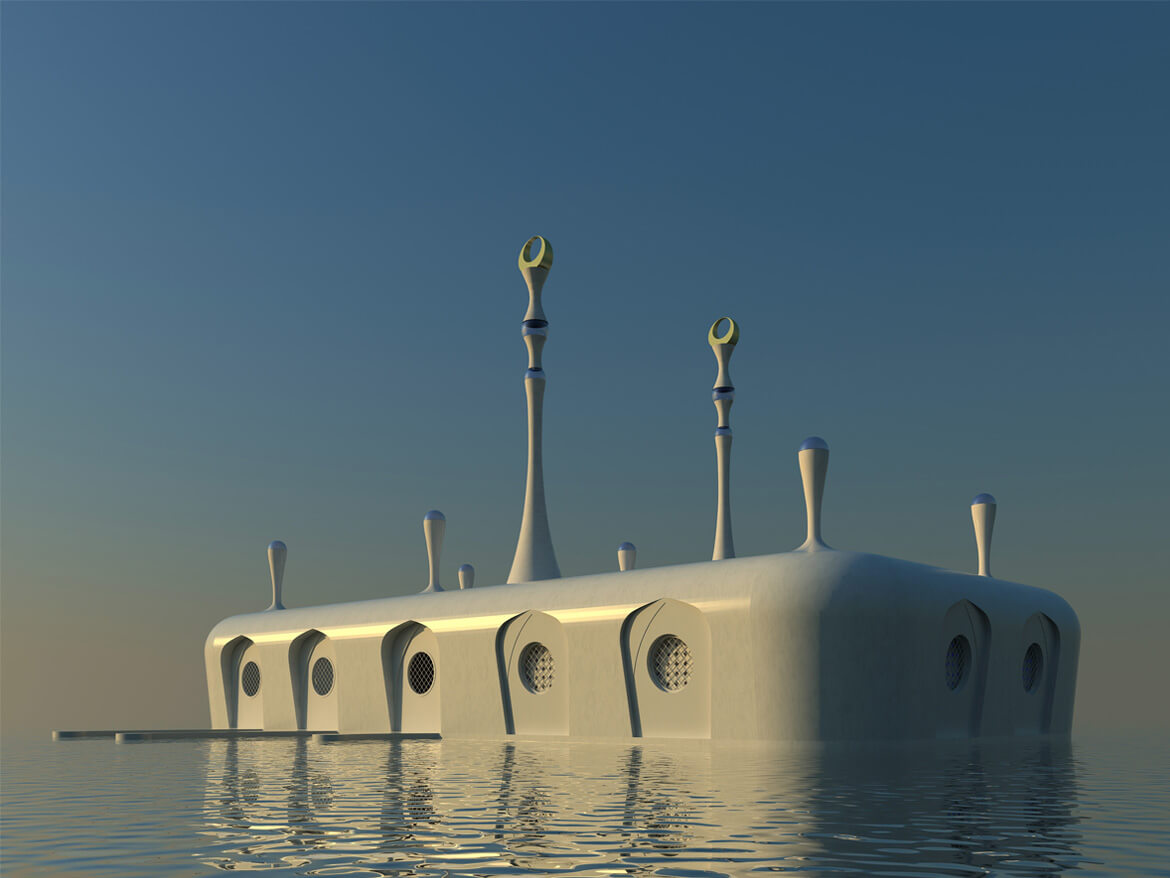

Vaak is niet precies bekend waar de sloppenwijken liggen, omdat ze op geen enkele officiële kaart staan aangegeven. Olthuis wilde hierin verandering brengen: ‘Middels het wet slum-project brengen we in samenwerking met UNESCO de bestaande sloppenwijken in kaart. Daarna onderzoeken we lokaal wat er nog ontbreekt aan voorzieningen en indien mogelijk leveren we die.’ De City Apps Foundation die Olthuis oprichtte leverde in Bangkok al een sanitair blok, in Dhaka een telecommunicatie-eenheid.

Klimaatverandering zal harder toeslaan in het Zuiden, onder andere door extreem weer zoals stormen of overstromingen door overmatige regenval. Drijvende huizen zijn hier even goed of zelfs beter tegen bestand dan “gewone” huizen volgens Olthuis. Ook natuurrampen zoals aardbevingen en tsunami’s zouden drijvende huizen moeten kunnen doorstaan.

Strijd tegen klimaatverandering

‘Daarnaast bieden drijvende voorzieningen ook de mogelijkheid tot directe noodhulpverlening in geval van rampen: we kunnen bijvoorbeeld een drijvende vluchtruimte naar Bangladesh brengen als overstromingen dreigen of sanitaire voorzieningen brengen als een ramp al heeft plaatsgevonden.’ Ook voor landen die sterk getroffen zullen worden door de stijging van de zeespiegel, zoals de Malediven, kan drijvend bouwen een oplossing zijn.

Bouwen op water is nuttig in de strijd tegen klimaatverandering, want drijvend bouwen kan, net als op land bouwen duurzaam en klimaatneutraal. Zo heeft de drijvende moskee die Olthuis bouwde een airconditioningsysteem dat water benut om de binnentemperatuur te doen dalen. Drijvend bouwen is ook veel minder schadelijk voor de ecosystemen onder water dan bijvoorbeeld landwinning.