Testing the Waters: Floating home development in Florida

By Amy Martinez

Florida Trend

February.2015

A 2013 U.S. Supreme Court ruling could lead to a first-of-its-kind floating home development in south Florida.

(Amy Martinez)

In 2005, Hurricane Wilma destroyed a pair of dilapidated marinas in North Bay Village where Fane Lozman, a former Marine pilot and software developer, kept a two-story floating home.

The Category 3 storm struck from the south, scattering splintered docks and other large debris into more than a dozen neighboring floating homes.

For years, Lozman had relished the camaraderie and convenience of living on Biscayne Bay, especially the easy access to deep-sea diving and fishing and his favorite Miami Beach restaurants. “Your speedboat was tied up right outside your front door. And you could enjoy the south Florida water lifestyle immediately and at any time,” he says.

After Lozman’s floating home, which had been docked at the north end of the marina community, emerged relatively unscathed, he quickly began looking for another place to anchor. In 2006, he had his home towed 70 miles north to Riviera Beach and rented a slip at a city-owned marina.

His new neighbors told him not to get too comfortable, however, because a planned, $2.4-billion marina redevelopment project soon would displace them. Lozman sued Riviera Beach to stop the project. And that led to another dispute, which eventually wound up before the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 2009, after failing to evict Lozman in state court, Riviera Beach went to federal court, seeking a lien for about $3,000 in dockage fees and nominal trespass damages.

The city argued that because Lozman’s floating home could move across water, it was a vessel under U. S. maritime law. A federal judge in Fort Lauderdale agreed, and the home was seized, sold at auction and destroyed by Riviera Beach, which cast the winning bid.

Lozman countered that his home was similar to an ordinary landbased house and should have been protected from seizure under state law. The home consisted of a 60-by- 12-foot plywood structure built on a floating platform — with no motor or steering — and could move only under tow.

Lozman’s appeal caught the Supreme Court’s eye. And in early 2013, it handed him a victory. Justice Stephen Breyer wrote in the majority opinion that because Lozman could not “easily escape liability by sailing away” and because he faced no “special sea dangers,” his home was not a vessel and not subject to seizure under maritime law. Lozman is still seeking compensation from Riviera Beach for his home’s destruction.

After the Supreme Court’s ruling, Kerri Barsh, a Greenberg Traurig attorney who helped argue Lozman’s case on appeal, contacted Netherlands-based Dutch Docklands, a developer of floating homes.

Founded in 2005 by architect Koen Olthuis and hotel developer Paul van de Camp, Dutch Docklands had designed hundreds of floating homes in Holland and was looking to expand to the United States. Barsh believed the high-court ruling created an opening for the company to pursue a first-of-its-kind floating home development in south Florida.

It meant, for example, that buyers could get a mortgage and homeowners insurance, though they’d also have to pay property taxes. The Coast Guard couldn’t enter their homes to inspect for life jackets and other safety measures — and “if a gardener or maid is injured on your property, you don’t have to comply with strict workers’ comp standards,” she says. “You also may be entitled to a homestead exemption.”

Dutch Docklands now is proposing a collection of multimilliondollar floating homes at a privately owned lake in North Miami Beach. Plans call for 29 man-made, private islands that are attached to the lake bottom with telescopic piles to guarantee stability.

Each island would cost an estimated $15 million and include a 7,000-sq.-ft. home, infinity pool, sandy beach and boat dockage, plus access to a 30th “amenity” island with clubhouse. The target market is celebrities and wealthy foreigners who want both privacy and proximity to downtown Miami, says Frank Behrens, a Miami-based executive vice president at Dutch Docklands.

“Buying your own island is a very complex process, and yet it’s a dream a lot of people aspire to,” he says. “Basically, what we’re offering is a way to realize that dream. Within two minutes, you can be on land and go to a Heat game or fancy restaurant.”

Historically, floating homes have not been widely embraced in Florida. A case in point is Key West’s Houseboat Row, which started in the 1950s as a playground for the rich, but in the 1970s deteriorated into floating shacks and live-aboards. In the 1990s, then-Mayor Dennis Wardlow repeatedly criticized Houseboat Row as an eyesore and environmental hazard. And by 2002, the community’s residents had been evicted and moved to a city-owned marina at Garrison Bight.

Today, the city marina has 35 floating homes and won’t accept any more. “We prefer to take in a registered marine vessel that’s Coast Guard certified,” says marina supervisor David Hawthorne. “Most marinas have moved out of it because of the liability, and there’s just more money in” short-term boat rentals.

To succeed in Florida, Dutch Docklands will have to change perceptions. The company promotes its brand of floating homes as a response to rising sea levels and climate change. And south Florida — as ground zero for sea level rise — could prove a receptive audience. Because of how they’re anchored, the floating homes move vertically with the tides, but not horizontally, enabling them to adapt to longterm climate changes and also hold steady in storms, Behrens says.

He hopes to begin construction next year at Maule Lake, a former limestone rock quarry with direct access to the Intracoastal Waterway. But his plans may be optimistic. The company recently filed for zoning approval and still faces questions about environmental impacts, the homes’ ability to withstand hurricanes and visual effects on the surrounding community.

“One of the big struggles we’ve had in this state is coming to grips with the fact that there’s a finite amount of land and water,” says Richard Grosso, a land-use and environmental law professor at Nova Southeastern University. “We tend to not recognize the importance of open space — the aesthetic and psychological value of it.”

Condominium towers — some pricier than others — surround Maule Lake. Behrens says local residents are understandably concerned about the project.

“If all of a sudden, a foreign developer comes and says, ‘Hey, we’re going to build private islands on this lake,’ I’d be upset, too,” he says. “But if you live in a $200,000 condo, and you get a $15-million private island on the lake in front of you, where a celebrity lives, you can imagine that the value of your real estate will go up.”

Even if all goes as planned for Dutch Docklands, it’s unlikely to spark copycat projects throughout Florida. Maule Lake presents “a pretty unique set of circumstances,” says Miami environmental lawyer Howard Nelson. At 174 acres, it’s big enough to accommodate a floating development without blocking boats — “and there’s very few bodies of water where the submerged land is privately owned,” says the Bilzin Sumberg attorney.

Meanwhile, Lozman has bought 29 acres of submerged land on the western shore of Singer Island in Palm Beach County. He says he’s talking with developers about building his own floating home community.

“I could see maybe 30 floating homes out there one day,” he says. “It would essentially duplicate the North Bay Village community that was destroyed in Wilma.”

Water Architecture: A chat with Waterstudio and Koen Olthuis

By Enrique Sánchez-Rivera

La Isla

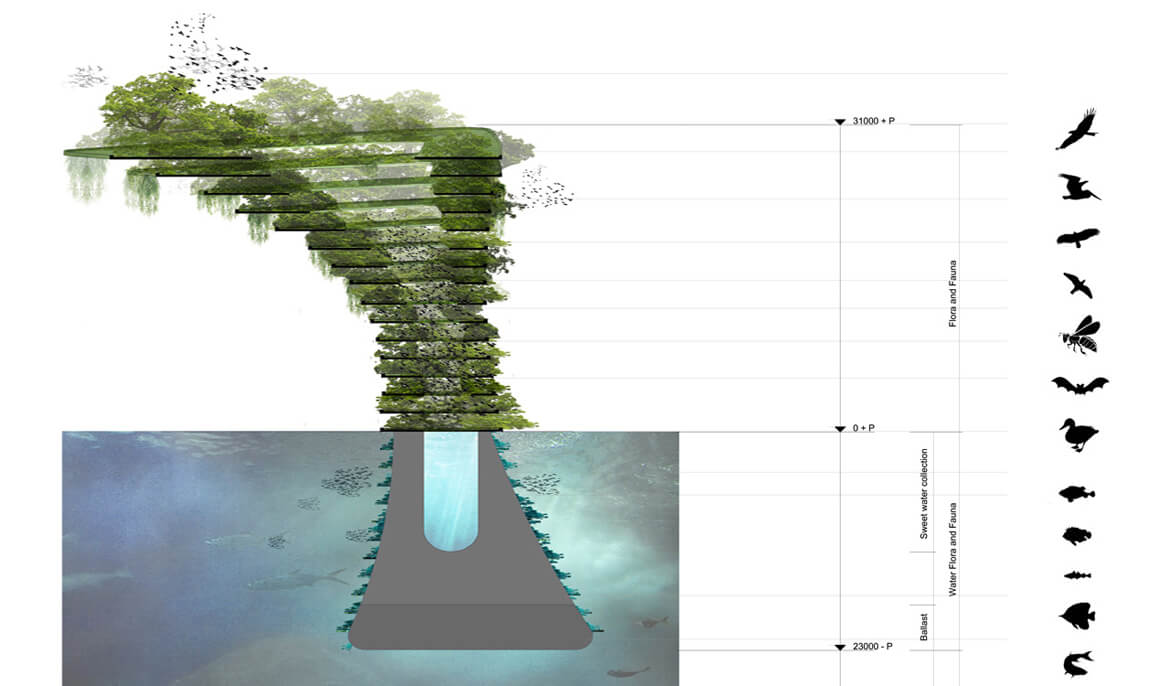

We were intensely captivated by Waterstudio after seeing them featured on National Geographic Magazine. Their incredible innovation skills and clear understanding about the future of architecture and our planet was obvious and ever so present in all of their plans and their current work. From a partially submersed ecological tower to floating islands in the shape of stars, Koen Olthuis and his team are shaping up the future for a post-antarctic ice meltdown era.

From sustainability to sustainaquality

Marina World, March 2013

Nestled in the Indian Ocean between Minicoy Island and the Chagos Archipelago, the Maldives comprise a chain of 26 atolls made up of islands and reefs. Tropical weather, white sand and clear water make the islands a popular holiday destination and a haven for divers but, while the surrounding ocean teems with life, home to coral reefs, eels, sharks, turtles, dolphins, manta rays and over 1,100 other species of fish, rising sea levels pose serious threat. Charlotte Niemiec reports on an ambitious community and tourism project aimed at keeping the Maldives afloat.

The average ground level in the Maldives is just 1.5m and the island’s president, Mohammed Nasheed, has warned that even a ‘small rise’ in sea levels would eradicate large parts of the area. Envisioning a future for its people of “climate refugees living in tents for decades” the Maldivian Government has teamed up with Netherlands- based company Dutch Docklands International in a Joint Venture Project to build a solution to the problem in the form of man-made floating islands. The ‘5 Lagoons Project’ will provide housing, entertainment and guest complexes for visitors to the Maldives, expanding its footprint and further bolstering the area’s tourist economy.

A star-shaped hotel and conference centre – the ‘Green Star’ – symbolises the Maldives route to combat climate change. Its many five- star facilities will include pools, beaches and restaurants. A ‘plug and play’ system allows for each leg of the star to be removed for easy refurbishment and a temporary one floated in and placed in position. It is hoped the centre will play host to international conferences on sea level rise, climate change and environmental issues. It is scheduled to open in 2015.

Across the water, relaxation is to be found at an 18-hole floating golf course. With panoramic ocean views, golfers can enjoy the driving range, short games practice areas, putting greens and a 9 hole par 3 Academy course. A separate area on the island provides romantic homes and townhouses in Venetian style, in a village offering boutiques, ice cream parlours, restaurants, bars and ultra- luxury palatial style villas. Movement around the island – assembled in archipelago form – is via bridges or glass tunnels in the ocean, which give guests the opportunity to enjoy the area’s sea life up close. A marina of international standard will also be built on this island.

Amillarah – the Maldivian word for private island – will consist of 43 floating islands offering luxury $10 million villas for sale to the public. Facilities will include a private beach, pool and green area, private jetty and small pavilion on a purpose-built island (the shape of which the buyer can design in advance), situated in the centre of an exclusive, large private water plot just a short swim away from the coral reefs. For those who baulk at the price tag, a separate development, the ‘Ocean Flower’ offers less expensive housing starting at $1 million. The Ocean Flower is located upmarket in the North Male atoll, 20 minutes by boat from the capital and airport, and will offer villas on three different scales. All have private pools and terraces and are fully furnished, while shared facilities include a beach, shops, restaurants, a diving centre, spa, swimming pools and easy access to the surrounding private islands. The Ocean Flower will open mid-2014, with construction beginning soon. Finally, the White Lagoon project consists of four individual ring-shaped floating islands each with 72 water villas connected. The rings function as beach-boulevards with white sand and greenery. A marina will be built inside the rings and a variety of restaurants, bars, shops and boutiques will be available.

Dutch Docklands is the master developer of the project and it controls the design, engineering, financing, construction and sales. It has appointed Waterstudio.nl as its architectural firm. Dutch Docklands CEO, Paul van de Camp, is excited about the project, viewing it as the beginning of large- scale floating projects in the area. He believes that if the project is successful, it will have proved the ability of the Maldives to combine the preservation of vulnerable marine life while expanding land for the reinforcement of tourism and urban developments at the same time. The project is an equally important one for the company and will be used as a benchmark business model for concepts around the globe. The joint venture with the Maldivian Government, which brings the needs and demands of the nation together with the commercial aspirations of Dutch Docklands is, van de Camp says, a very solid and long- lasting basis for such a big project.

Understandably, there are significant challenges to be faced when building on water. The biggest, van de Camp explains, is logistics: “We build most of the floating structure off-site, in a production yard outside the Maldives, and larger parts in the shipyards around the Indian Ocean and in the Netherlands. To get all the floating products there at the right moment (‘just-in-time’ management) at the final location ready for assembling is a pretty tough task.”

However, building on the ocean also has distinct advantages over building on land, as Dutch Docklands’ co- founder Koen Olthuis explained last year at the UP Experience Conference in Houston, USA. In the open ocean, tsunami waves are mere ripples beneath a structure that floats; water is the perfect shock absorber to seismic waves; and concerns over sea-level rise are eliminated when your home rises with it.

The islands will be constructed using patented technologies, which include the use of very lightweight Expanded Polystyrene (EPS) components and strong concrete structures. In line with Dutch Docklands’ focus on ‘scarless developments’, the materials used are environmentally-friendly, causing hardly any impact to marine life. Paul van de Camp emphasises that any possible impact on the environment is noticed upfront, while the design is on the drawing board. Using the expertise of marine specialists, marine engineers and environmental consultants, the design is adjusted at the first sign of negative impact.

At a cost of over $1 billion and funded by private shareholders, the developments are luxury resorts, catering for the more elite visitor. But van de Camp explains that the 5 Lagoons Project aims to provide a whole range of resort and business activities from reasonably-priced to ultra-luxurious. The Green Star hotel will provide the best-priced rooms, with the floating palaces in the golf course at the top end of the market.

With headquarters in The Netherlands, Dutch Docklands has a long and varied history with water. Its home country has battled against water for centuries – 20% of the country lies below sea level and water is controlled using dikes and canals. Koen Olthuis has a vision of the future in which we do not fight water but live with it and upon it. A man inspired by out-of-the- box inventions such as the elevator, which allowed cities to build up rather than span out horizontally, Olthuis sees water as another platform on which to build. It is his belief that, as so many of the world’s cities lie close to water, we should utilise this space and not just defer to the argument that there is no more space. Paul van de Camp shares this vision of a future in which floating developments are commonplace, creating new space and saving threatened ocean nations.

Meet the man who builds things on water, from slum schools to $14 million villas

Quartz, Siraj Datoo, Aug 2013

Dutch architect Koen Olthuis specializes in building things that float. His structures, he concedes, use a similar technology to oil rigs. Yet Olthuis’s focus is elsewhere—on combating rising sea levels, floods, and a growing world population. As he outlined in a TEDx Warwick talk last year, the work he’s doing is quite literally putting land where there wasn’t any before.

Olthuis is the founder of architectural firm Waterstudio.NL, and as a native Dutchman, he often cites his own country’s history as inspiration. “In Holland, we have always been fighting against the water… 50% is under sea level,” he said in his talk. Yet he finds this ongoing battle with water “strange”, arguing that it makes the country susceptible to danger. “What if something breaks?” he said in a phone call with Quartz. His solution: “Why don’t we just use the water?”

His projects include designing homes in Holland, schools in slum neighborhoods in Bangladesh, “amphibious houses” in Colombia, a star-shaped conference center, and a 32-island golf course (with, yes, underwater glass tunnels linking the islands) in the Maldives. He’s also looking to sign a contract to design villas in Florida.

How does it work?

There are three main elements here. The floating base:

[It] is the same technology as we use in Holland. It’s made up of concrete caisson, boxes, a shoebox of concrete. We fill them with styrofoam. So you get unsinkable floating foundations.And the bit on top?

The house itself is the same as a normal house, the same material. Then you want to figure out how to get water and electricity and remove sewage and use the same technology as cruise ships.

How it is anchored to the ground?

In Dubai, they just put sand into the water and made artificial islands. Once you put sand into the water, you can’t go back. We can go back after 150 years and there’s no damage to the habitat.

That’s impressive. So what do you do exactly?

[In the Maldives], these houses are connected to a floating boulevard… Those are connected to the sea bed with telescopic piles and as the boulevard rises up from sea level and the house rises up.And all that means that if there’s a rise in the sea level, due to a flood or tsunami, the island will just rise?

Yes.

“We don’t believe in donating money,” he tells me. “It didn’t work in the history [sic] and it won’t work in the future.” When you give money to charity, he argues, you rarely know what impact it has had.

His response to this is the City Apps Foundation. Instead of donating money for food and aid, companies provide financing for “apps”—interchangeable, prefabricated units such as classrooms, social housing, first-aid stations, or even parking lots. Like the apps on a smartphone, they’re designed to be easy to install and launch with the minimum of fuss. After an initial free trial, schools, governments and local municipalities can lease specific “apps” for a monthly fee. The fees yield a return for the investors, and when the apps are no longer needed they can simply be packed away and assembled in another city. The foundation has raised funding from a number of Dutch companies, and Olthuis and his company provide the technology.

The foundation’s first major project is a school in a slum in Dhaka. Olthuis says that slums have specific problems that appeal to him—in particular their instability. At any moment “the government can say that we’ll take the slums out or landlords might kick them out,” so slum-dwellers tend not to invest in their communities.

City Apps gives power to these neighborhoods, Olthuis argues, especially because they are often situated on the edge of water. In Dhaka, the school app will be a white container that stands out from the rest of the slum to create what Olthuis, perhaps inadvisedly, calls a “shock and awe effect”. The schools will contain iPads for use by the students, and women will use the space for evening classes. Within 12 weeks, the schools will have been built, transported to Dhaka, assembled and ready to use. If the community is forced to move, the school can move too with relative ease.

Olthuis says there are two ways that the City Apps foundation is a better system for investors:

It provides accountability. Cameras inside the containers will allow investors in the project to show off the fruits of their social spending to clients or shareholders in real time.

Although the initial school app will be free, slum-dwellers will have to pay to lease extra apps, such as what Olthuis calls “functions” for sanitation (this could be anything from a toilet to a fully-fledged bathroom) — or even just the ability to print. If the slum no longer wants a specific “function”, it can be easily taken away and used elsewhere. Investors get money if more “apps” are leased

“[It’s] stupid that each [sic] four years, we build complete neighborhoods and then they leave it there.” And it kind of is. The British government spent almost £2 billion ($3.1 billion) on venues alone for the Olympics and Paralympics village for London’s 2012 games. Instead, Olthuis suggests, Olympic cities should lease floating stadiums and property. This could be assembled in advance of the games and packed away afterwards, and would be far cheaper than creating new stadiums and neighborhoods every four years. While it would certainly remove some of the sparkle around the event, it would cut a good deal of waste. In Britain, talk of how the OIympic venues could be used after the games has already faded away.

Work on the “ocean flower”, part of a project that will see 185 new floating villas, has already begun and the first villa will be inhabitable as soon as December this year. Americans, Chinese, Russians and even hotel operators have already forked out the $1 million cost per villa.

Olthuis has a contract with for 42 amillarah islands (private villas in the Maldivian language). These will be 2,500 sq. meters (26,910 sq. feet), and, at $12 million-$14 million, for the “stupidly rich”, Olthuis lets slip.

You can take a speedboat-taxi from the airport in 15 minutes or a three-person “U-boat” submarine will get you there in 40. (Russian president Vladimir Putin was seen modelling the five-person version.) Alternatively, spend three weeks learning how to maneuver a U-boat and a license is yours.

What if there was a hotel-cum-conference center in the middle of the ocean? Construction on this complex will begin towards the beginning of 2014 and with it come some interesting innovations. While a starfish has five “legs”, Olthuis’s company will build six. This means that if a section needs to be renovated, they could replace one leg with the spare (kept at the harbor) within three days instead of having to cordon off the area for months.

In his TEDx Warwick talk, Olthuis jokes that even if you’re on honeymoon in the Maldives, after a few days of glorious swimming, you kind of just want to play golf. And while the golf course might not be swarming with newly-weds, it might attract a new set of tourists from Russia and China.

Even if you’re not much of a golfer, it’s likely you’ll make a trip just to walk in the underground tunnels between the islands. And yes, the tunnel will be transparent.

Colombia has three big flood zones and every time there’s a flood, local municipalities have to pay a lot of money in compensation, according to Olthuis. To combat this, the local government has signed up Waterstudio.NL to build 1500 “amphibian” houses with a floating foundation.

So while the above photo depicts a floating house in a dry season, the house will simply rise in a wet season. While it’s a fairly simple concept, it has radical implications.

Olthuis’s biggest impact so far has been in Holland, where a number of water villas have already been completed. With over 50% of the country below sea level, this provided the perfect playground for his concepts to become a reality