Flotter vers Léau-dela

By Gabrielle Anctill

Esquisses

2016 volume 27 nr 1

Projets exemplaires

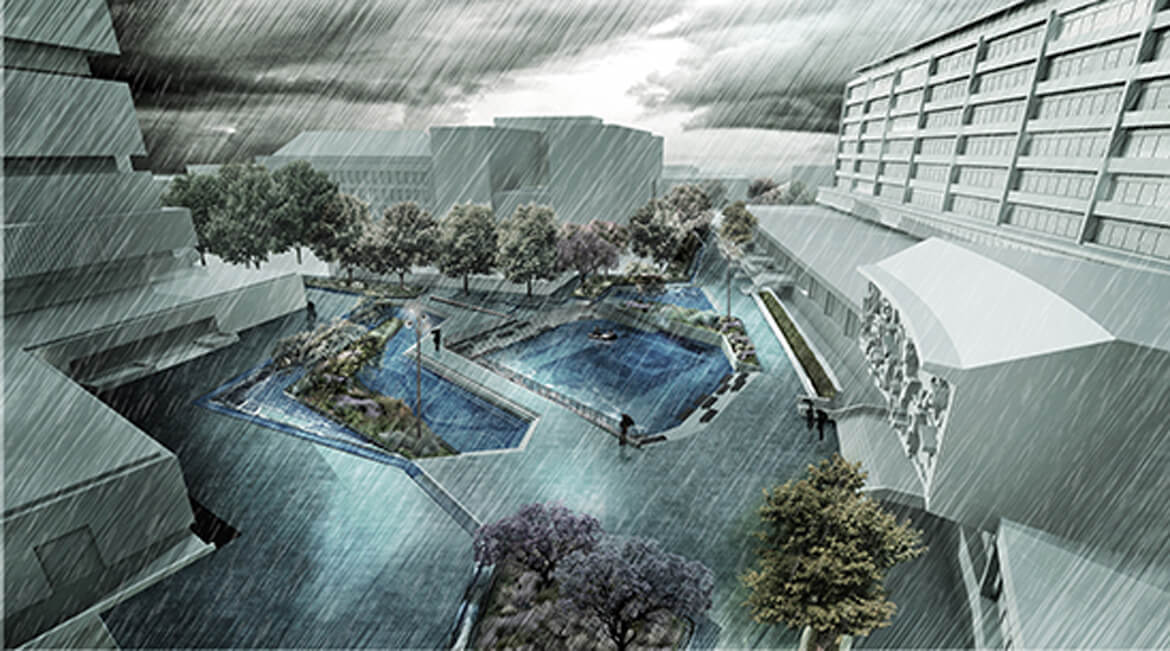

Carré d’eau

Waterplein (square d’eau), Rotterdam (Pays-Bas), De Urbanisten. Illustration: De Urbanisten

L’ennemi des villes de demain sera l’eau. En première ligne, Rotterdam aux Pays-Bas, qui doit se préparer à combattre les pluies torrentielles causées par les changements climatiques. Pour vaincre les flots, une arme : la place publique.

Gabrielle Anctil

Plutôt qu’une catastrophe à prévenir, la Ville de Rotterdam a décidé de voir les changements climatiques comme une occasion à saisir. C’est pourquoi elle a mandaté en 2005 la firme de recherche urbaine et de design De Urbanisten pour trouver des solutions novatrices en matière de gestion de l’eau. De ces réflexions a émergé l’idée du waterplein ou « square d’eau », une place publique servant aussi de bassin de rétention des eaux.

« La mission du square est de réconcilier la population avec l’eau. Nous voulions créer la même magie que lorsqu’un enfant joue dans une flaque d’eau », explique Dirk Van Peijpe, ingénieur et cofondateur de la firme. Un premier spécimen, le Waterplein Benthemplein, a vu le jour en 2013. Composé de trois bassins de différentes profondeurs, le plus profond faisant office de terrain de basketball, il est conçu pour servir principalement d’espace public. La communauté, qui a participé pleinement à sa conception, se l’est rapidement approprié : en plus des sportifs et autres flâneurs, on peut même y croiser des fidèles assistant à un baptême, gracieuseté de l’église avoisinante.

Lors d’une averse, les trois bassins servent à stocker l’eau de pluie. Avec style. « Nous avons voulu mettre l’accent sur le design », précise Dirk Van Peijpe. Ainsi, les gouttières en acier inoxydable qui transportent l’eau depuis les bâtiments adjacents vers les bassins sont assez larges pour accueillir les planchistes par temps sec. D’autres détails permettent de contrôler la façon dont l’eau atteint les bassins, pour rendre le tout le plus spectaculaire possible. Une fois les égouts libérés, l’étang cède de nouveau l’espace à la place publique.

Le square d’eau est un concept qui porte ses fruits : la firme en planifie déjà un deuxième dans la ville de Tiel, toujours aux Pays-Bas. « La beauté du square, c’est que nous avons repris une idée simple : l’eau descend », souligne Dirk Van Peijpe. Comme quoi certaines idées novatrices coulent de source…

Soigner contre vents et marées

Hôpital Spaulding, Boston (États-Unis), Perkins + Will. Photo : Anton Grassl/Esto

Sous sa façade grise, l’hôpital Spaulding est comme Superman dans les habits de Clark Kent. Portrait d’un bâtiment prêt à tout.

Gabrielle Anctil

L’ouragan Katrina qui a frappé La Nouvelle-Orléans en 2005 a causé un choc dans le milieu hospitalier américain. « Le monde médical a vu les hôpitaux hors d’usage et s’est dit : plus jamais », se remémore Robin Guenther, architecte et associée principale chez Perkins + Will, une firme d’architecture américaine. Mais, lorsque l’ouragan Sandy est tombé sur New York sept ans plus tard, les télévisions ont encore une fois relayé les mêmes images.

C’est avec ces leçons en tête que l’architecte s’est attelée à la conception de l’hôpital Spaulding, à Boston. « Notre client était parfaitement conscient de ce qui s’était passé à La Nouvelle-Orléans et voulait construire un hôpital qui résisterait aux effets des changements climatiques », explique Robin Guenther. Situé dans le port, le bâtiment devait absolument être à l’épreuve de la hausse du niveau de l’eau. Une mission de taille, compliquée par la quantité de données avec lesquelles jongler. Élever le bâtiment était une évidence, mais quelle sera l’élévation du niveau de la mer dans 50 ans ? Comment composer en même temps avec les besoins d’accessibilité d’une clientèle à mobilité réduite ?

L’élévation du bâtiment n’est qu’une des multiples caractéristiques qui le préparent au pire : les génératrices sont situées sur le toit, plutôt qu’au sous-sol, emplacement inondable où on les trouve habituellement, les fenêtres peuvent s’ouvrir et la végétalisation des toitures contribue à réduire les îlots de chaleur.

Les architectes ont tenté de penser à tout, sans pour autant faire exploser les coûts. En fait, moins de 1 % du budget total a été consacré aux mesures d’adaptation aux changements climatiques. Pour Robin Guenther, c’est une évidence : « Quand on y réfléchit à l’avance, comme nous l’avons fait, les coûts sont minimes, alors que réaménager un bâtiment déjà construit coûte extrêmement cher. D’où l’importance de parer dès la conception à la prochaine tempête du siècle. »

Il semble bien que l’hôpital Spaulding sera prêt à l’affronter.

Les jardins suspendus de Milan

Bosco verticale (forêt verticale), Milan (Italie), Stefano Boeri. Photo: Paolo Rosselli.

Le rêve de l’empereur Nabuchodonosor II serait-il devenu réalité ? Devant la menace des changements climatiques, l’idée de verdir en hauteur comme à Babylone n’a plus rien de fantaisiste, tel que le démontre le projet Bosco verticale de Milan.

Gabrielle Anctil

En construisant à Milan les deux tours d’habitation du projet Bosco verticale (forêt verticale), l’architecte italien Stefano Boeri ne voulait pas que leur architecture soit uniquement ornementale. « Les bâtiments sont volontairement plutôt sobres, explique le concepteur. Ce qui compte le plus, c’est l’intégration de la nature. »

Les tours de Bosco verticale sont, comme leur nom l’indique, couvertes de végétation. Mais Stefano Boeri a vu plus loin que les toits verts que l’on connaît déjà : sur les balcons des bâtiments poussent de vrais arbres. « En fait, chaque habitant en a deux, plus huit arbrisseaux et 20 plantes. » Beaucoup plus original qu’une cour de banlieue, et surtout, bien plus durable. « Les villes doivent être plus denses, rappelle l’architecte. Nous ne pouvons plus nous permettre de maintenir le rêve de la maison de banlieue. »

Pour Stefano Boeri, la nature a un rôle primordial à jouer dans la lutte contre la pollution des villes. « Les arbres permettent d’absorber la poussière ambiante et le CO2, de minimiser l’impact des îlots de chaleur urbains et de réduire la température à l’intérieur des logements pendant l’été, réduisant du même coup la consommation d’électricité », énumère l’architecte. Une attention toute particulière a d’ailleurs été accordée au choix des arbres afin de maximiser leurs bienfaits. Ainsi, du côté nord, on a sélectionné des essences à feuilles caduques pour laisser le soleil réchauffer les logements en hiver.

Toute originale qu’elle soit, la forêt verticale doit pouvoir être reproduite à moindre coût pour avoir un réel impact. « Il est tout à fait possible de copier-coller l’idée n’importe où dans le monde, à condition de sélectionner des arbres adaptés au climat », affirme Stefano Boeri. L’architecte s’est d’ailleurs vu confier la mission de concevoir une ville de 100 000 habitants en Chine, selon le modèle de ses tours milanaises.

Si l’idée prend racine, les enfants de demain pourront peut-être grimper aux arbres… sur leur balcon.

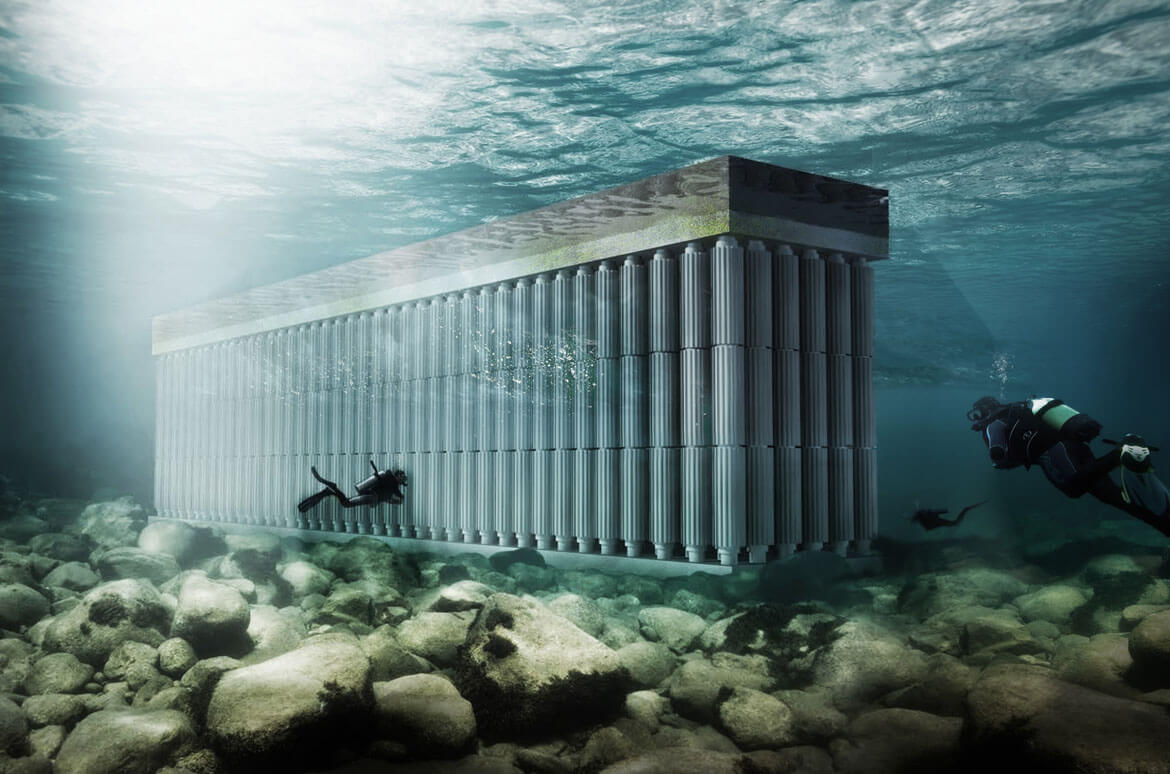

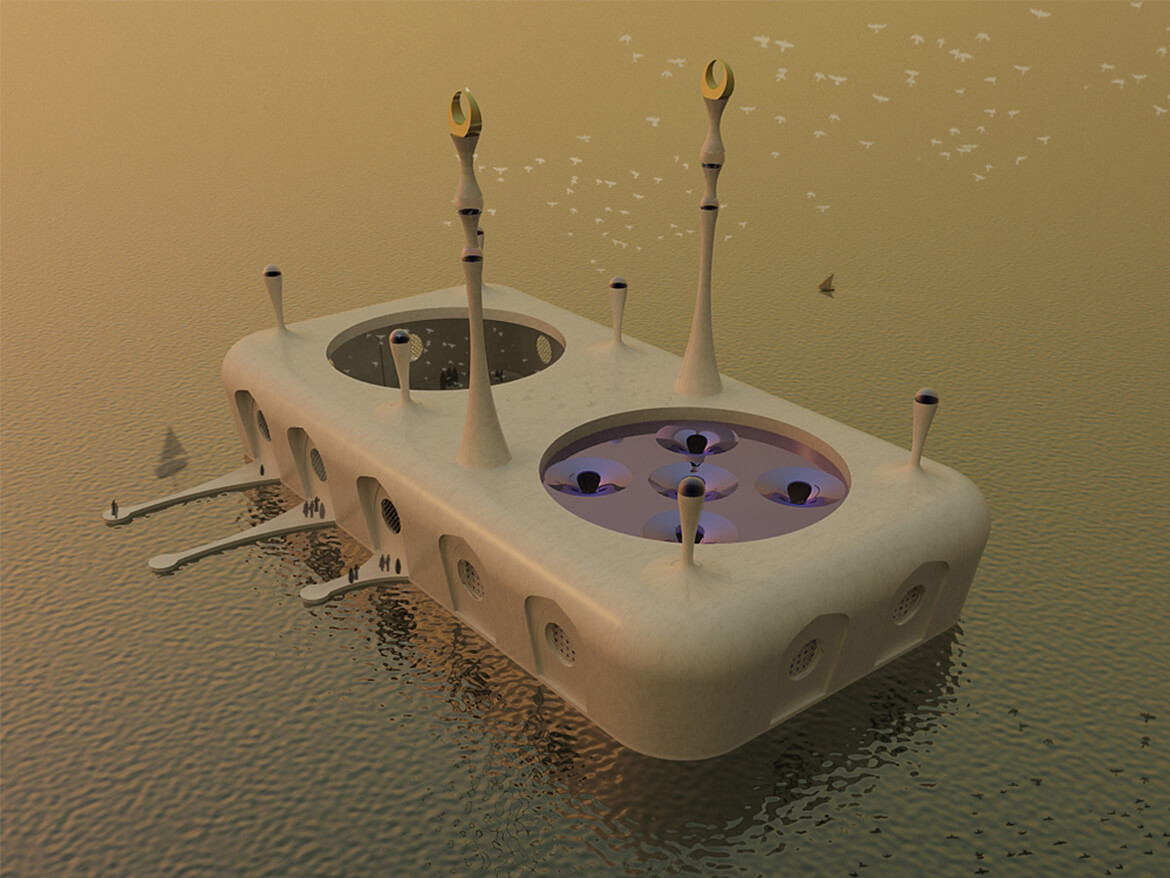

Flotter vers l’au-delà

Concept de mosquée flottante à Dubai (Émirats arabes unis), Koen Olthuis Waterstudio.NL. Illustration : Koen Olthuis – Waterstudio.NL et Dutch Docklands

Une mosquée flottante? L’idée peut sembler loufoque, voire sacrilège. Pourtant, ce type de construction est peut-être la solution idéale pour défier les inondations dans les villes de demain.

Gabrielle Anctil

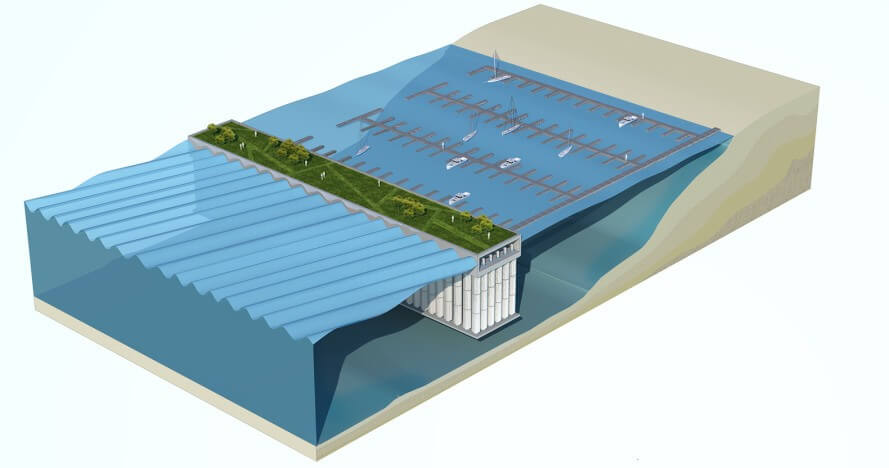

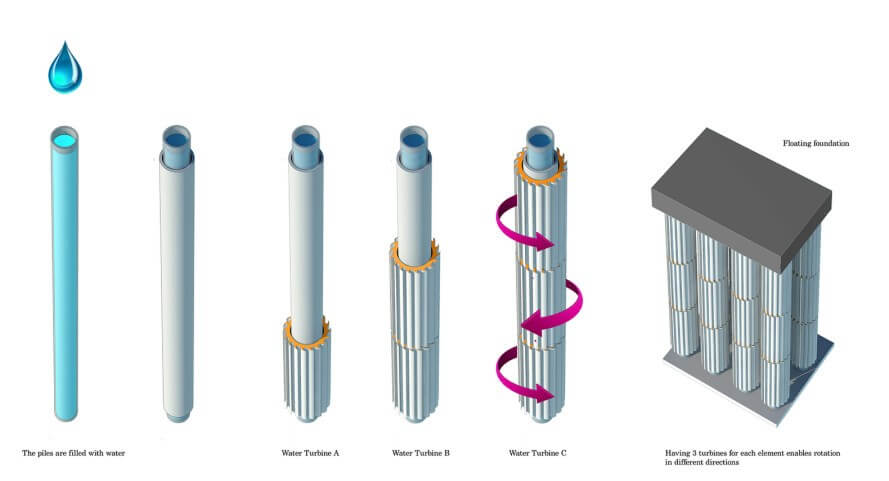

La firme Waterstudio, de l’architecte néerlandais Koen Olthuis, ne construit que sur l’eau. Quand on lui demande pourquoi, le fondateur répond du tac au tac : « On est en sécurité sur l’eau. Plus besoin de s’inquiéter des inondations. » Pour étonnant qu’il soit, le concept n’a rien de nouveau. « Aux Pays-Bas, on construit sur l’eau depuis plus de 200 ans », affirme l’architecte.

Son expertise a mené Koen Olthuis à travailler à Dubai, aux Émirats arabes unis, où on lui a confié en 2007 le mandat de concevoir un lieu de prière inédit : une mosquée flottante. En plus d’avoir les deux pieds dans l’eau, le bâtiment utilise les flots comme système de climatisation. « En été, les températures montent jusqu’à 50 °C, mais l’eau reste toujours à environ 27 °C », explique l’architecte. L’eau est pompée à travers les murs et passe par le toit avant de retourner dans le golfe Persique, rafraîchissant l’air au passage.

Un bâtiment flottant ne pose-t-il pas des contraintes architecturales importantes ? « Pas du tout, affirme Koen Olthuis. Mise à part la fondation, qui doit s’adapter au type d’écosystème où on la placera, l’architecture est presque identique à celle d’un bâtiment traditionnel. » Le plus gros défi ? Changer la perception du public. À Dubai, l’idée d’une mosquée sur l’eau a causé des remous dans la communauté. « Il y avait des débats à la radio où on se demandait si la mosquée serait assez sacrée ! » se remémore l’architecte. La conclusion ? Oui, mais seulement si elle pointe toujours dans la direction de la Mecque.

Retardé par une économie vacillante, le projet ne verra peut-être jamais le jour. Mais si on en croit Koen Olthuis, les constructions flottantes sont la voie de l’avenir. « On peut construire presque n’importe quoi sur l’eau. Avec l’urbanisation accélérée et les coûts élevés des terrains dans les villes, l’idée de construire sur l’eau devient une évidence. » À quand un quartier flottant au Québec ?