A floating city in the Maldives begins to take shape

Hub of floating architecture

A normal city, just afloat

CNN style

2022.June.20

By Kate Springer

CNN

July.11.2016

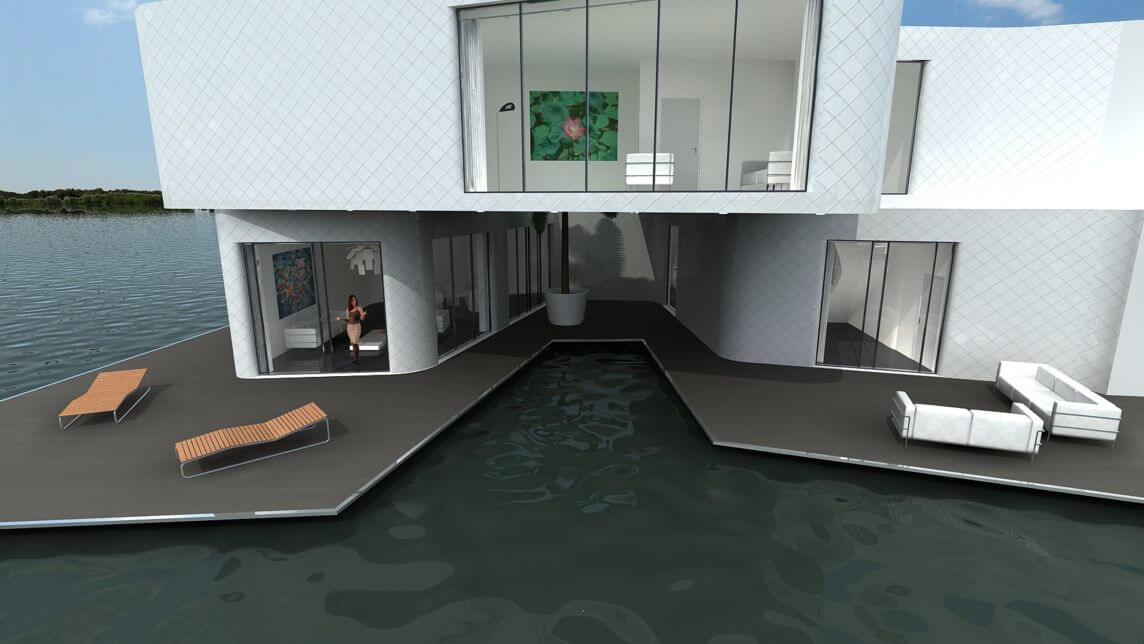

Citadel, Westland

An ambitious project from Dutch developers ONW/BNG GO, the Citadel is Europe’s first floating apartment building. It’s part of the New Water development project, which will comprise six floating apartment buildings — all designed to adapt to flooding and rising water levels.

CNN, Barry Nield, August 2014

The 86-room Krystall hotel is scheduled to be built off the coast of Tromso, Norway, in 2016.

Citadel one of the 10 eye-popping new buildings that you’ll see in 2014

CNN, Will Tidey

Water hazard! $500 million floating golf course planned for Maldives. “Koen Olthuis’ vision will be realized when work officially starts on the project later this year”

CNN, Will Tidey

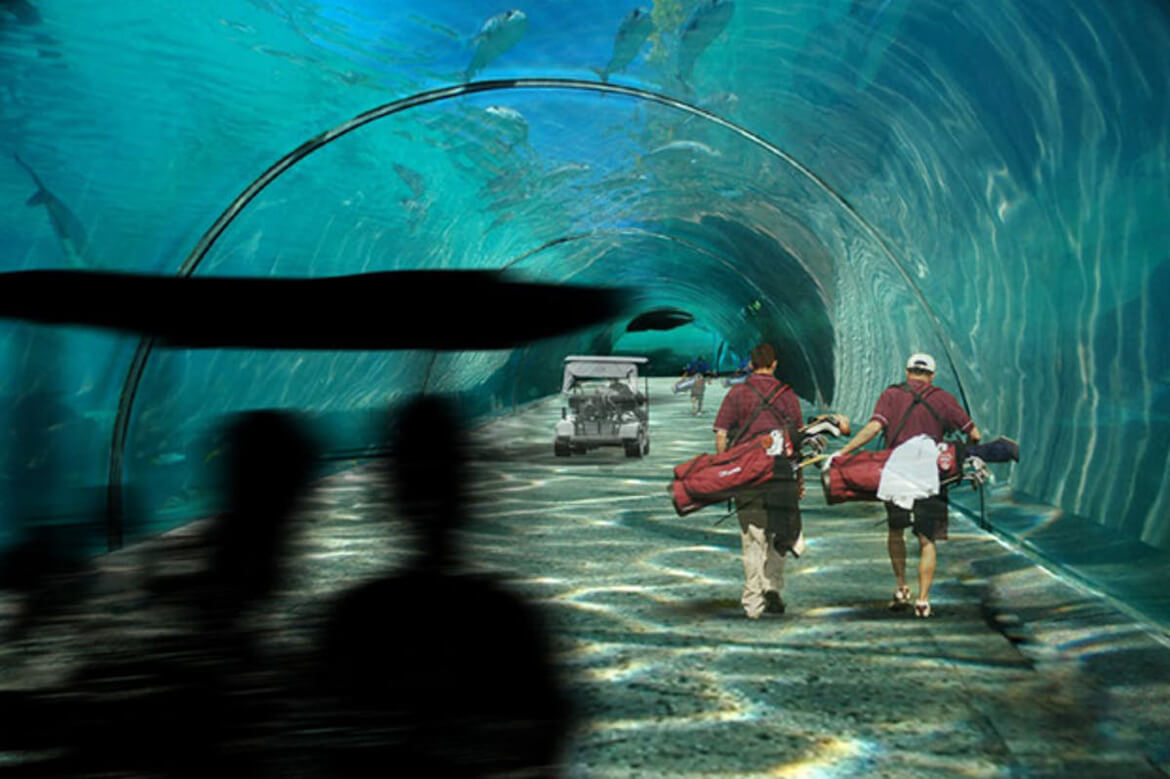

You’ve just finished a round of golf on a floating course in the middle of the Indian Ocean. An underwater tunnel leads you to the clubhouse, where a glass elevator drops down to a main bar that doubles as a spectacular natural aquarium.

It might sound far-fetched, but a $500 million development in the Maldives is set to make the world’s biggest water hazard a reality — and at the same time offer a potential long-term solution to the threat of climate change in the area.

Designed by floating architecture specialists Dutch Docklands, the proposed site is just a five-minute speedboat ride from Maldives capital Male, and will offer 27 holes of golf, set upon three interlinked islands.

The government-approved development will also boast around 200 villas, 45 private islands and a conservation center — and all at little or no cost to the wildlife-rich coral reefs it will call home, according to the people behind it.

“We told the president of the Maldives we can transform you from climate refugees to climate innovators,” said Paul van de Camp, CEO of Dutch Docklands.

“And we have a way of building and sustaining this project that is environmentally friendly too. This is going to be an exclusively green development in a marine-protected area.”

With over 80 percent of their 1,190 coral reef islands no more than a meter above sea level, the Maldivian government is at the forefront of the battle against climate change.

As sea levels reach dangerous levels, one option is to build defense walls, as they have around Male. Another is to buy land from other countries and effectively move their population to other areas. The third is to live on floating landscapes.

“Climate change is upon us and the Maldives are feeling it most. That’s why they’re leading the way in trying to find a way to combat the problem.” said Mark Spalding, senior marine scientist at the Nature Conversancy.

“But building on floating islands clearly comes with a risk of pollution. Golf courses need pesticides and you need to deal with that properly to make sure it doesn’t get into the ocean. There’s also the issue of desalinating the water to irrigate the course. That has to be done cleanly too.”

Dutch Docklands appear to have a green solution. They plan to capture pesticides in concrete troughs, and recycle them in a fresh water “sweet lakes” in the middle of the golf course afterwards. That same water will then be used to irrigate the course.

When it comes to the environmental cost of constructing the islands and developments in the first place, the solution is far more straightforward.

“We’ll be building the islands somewhere else, probably in the Middle East or in India,” said designer Koen Olthuis, the man whose vision will be realized when work officially starts on the project later this year.

“That way there’s no environmental cost to the Maldives. When it comes to the golf course, the islands will be floated into position first, and then the grass will be seeded and the trees planted afterwards.”

Troon Golf, who will be lending their expertise to the project in designing the course itself, stressed the economic benefits that could result from the construction in a release issued from their headquarters in Zurich, Switzerland.

“The scar less development, which has zero footprint on the Maldives region will include state-of-the-art golf courses that look set to bring a wealth of new tourism and investment to the country,” said managing director Bruce Glasco.

But Spalding is not getting carried away. With some of the world’s most valuable coral reef real estate at stake, he plans to watch the development closely and treat all environmental claims with caution.

“I just hope the Maldives government have been wise enough to not just fall for rhetoric,” he said.

“In an ideal world a development like this would be on land, but the world is changing. I just hope they get it right. If they do, this type of development could be a harbinger of things to come.”

If things go to plan, Van de Camp expects the golf course to be ready for play by the end of 2013, will the full development set to launch in 2015. And he’s in no doubt visiting golfers will be in for a treat.

“This will be the first and only floating golf course in the world, and it comes with spectacular ocean views on every hole,” he said.

“And then there’s the clubhouse. You get in an elevator and go underwater to get to it. It’s like being Captain Nemo down there.”

TIME Magazine

TIME asked who you thought should be on the list of the 100 most influential people of the year. Koen Olthuis was chosen thanks to his worldwide interest in water developments.

TIME Top 100

TIME asked who you thought should be on the list of the 100 most influential people of the year. Koen Olthuis was chosen thanks to his worldwide interest in water developments.