The Floating Dutchman

By Kerstin Schweighöfer

FUTURE PERFECT

December 2015

Koen Olthuis | © Architect Koen Olthuis, Waterstudio.NL

The Citadel is a floating apartment complex near Naaldwijk, Netherlands. | © Architect Koen Olthuis, Waterstudio.NL

THE FLOATING DUTCHMAN

In the tradition of his water-taming nation, Dutchman Koen Olthuis designs floating islands to dwell and live on – not least because climate change calls for new solutions in architecture.

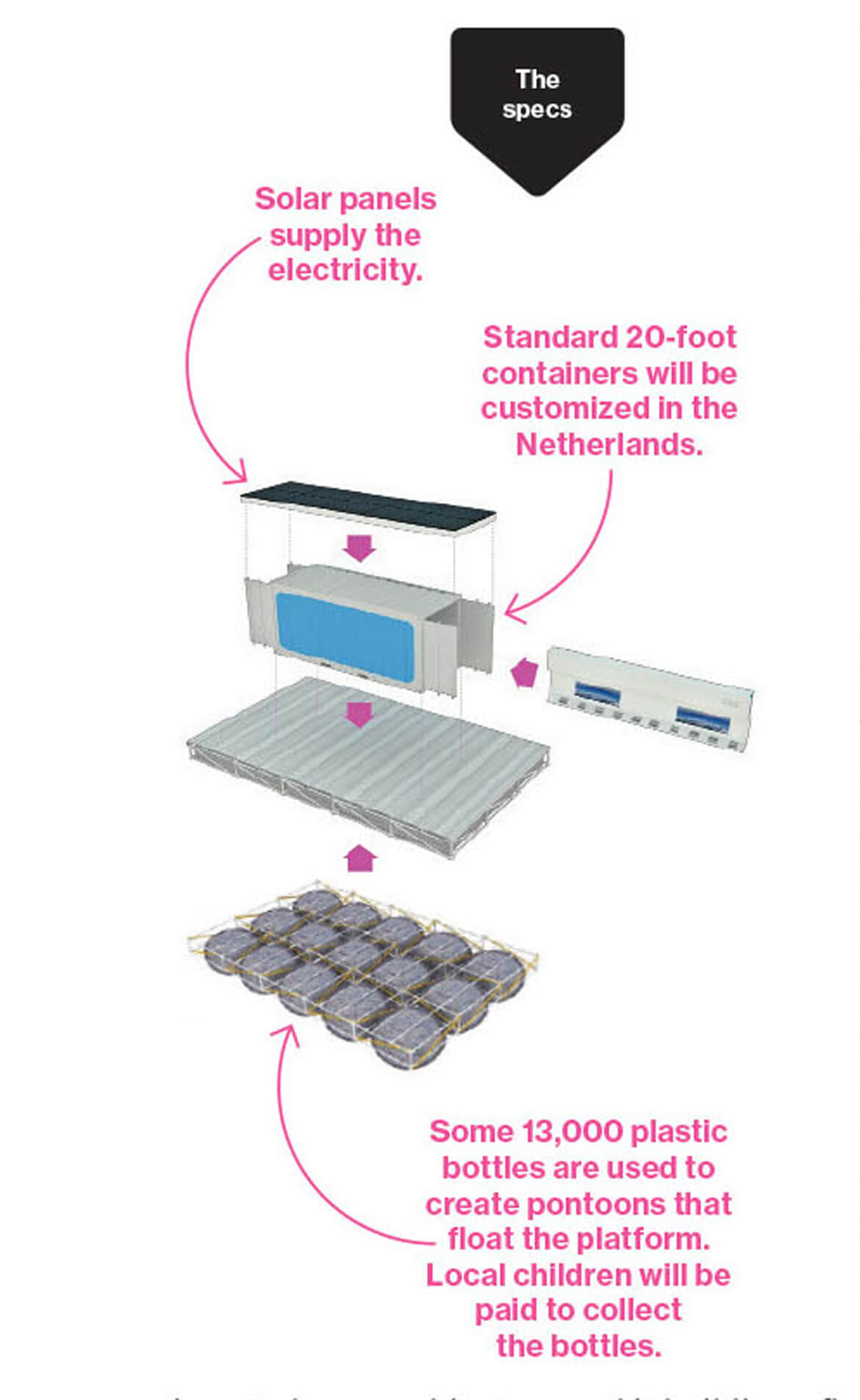

A vacation doesn’t get more wonderful than this: a white sandy beach, a green-blue, glistening sea and an exotic underwater world to thrill any snorkeling enthusiast. All you have to do to explore it is jump into the Indian Ocean from your personal jetty, because the elegant vacation villa where you’re staying is floating on the water. In a Maldivian lagoon, this dream is currently becoming a reality as the construction of 185 floating vacation homes is currently underway. They’re arranged in the shape of a giant flower on the water. Hence the name of the project: Ocean Flower.

It was designed by Koen Olthuis, a Dutch architect who is considered a pioneer of what is called Aqua Architecture: “I build exclusively on the water,” says the 44-year-old with a strawberry-blonde mop of curly hair. His buildings are made to withstand floods and climate change because everything Olthuis designs can adapt to the level of the sea. It is not by accident that his office in Rijswijk near The Hague bears the name waterstudio.nl.

Bracing for climate change, without leaving a trace

In order to make such bold projects as the Ocean Flower a reality, Olthuis partnered with a fellow Dutchman, project developer Paul van de Camp, to found the company Dutch Docklands. It buys water properties all over the world to use them as building sites. This opens up completely new perspectives – not only for densely populated cities or countries where building sites are in short supply and hence, expensive: “It also helps residents protect themselves from the consequences of climate change.”

There is a reason Dutch Docklands launched its first project in the Maldives. It’s not just to cater to the recreational interests of spoiled tourists: The 300,000 inhabitants of the island nation will soon literally be up to their necks in water, because 80 percent of the Maldives are located barely a metre above sea level. The government had already announced plans to buy to land elsewhere in order to survive. Until Olthuis and van de Camp assured them that this was quite unnecessary: “We made the President of the Maldives understand that climate refugees can be pioneers of climate management,” said Olthuis. They understood immediately.

The Ocean Flower is just the beginning: Four more lagoons with floating vacation lodges are to follow, as well as a floating conference centre and one of the world’s most spectacular golf courses that will spread over several man-made islands to be connected by underwater glass tunnels.

And all this can be done without leaving a trace in nature or inflicting any damage, for Dutch Docklands is committed to what it calls the scarless approach: “Our units can float anywhere on the water for 200 years, yet if the area is needed for some other purpose, they can just be hauled away,” Olthuis explains. They will be gone without a trace.

The Dutch know how to live with the water

It isn’t surprising that the pioneers of Aqua Architecture are Dutch: Like no other people, the nation at the mouth of the Rhine River has spent centuries learning to tame the water or to keep it in check with dikes, dams and levees. As the proverb goes: “God created the world – and the Dutch the Netherlands.”

Whether it is in New Orleans or in Bangladesh: The expertise of Dutch hydraulic engineers and architects is in high demand throughout the world – today more so than ever, thanks to climate change, which brings swelling rivers, rising sea levels and more catastrophic floods around the globe.

The Dutch have long recognized that building ever higher dams won’t be enough. Therefore, the former nemesis is instead given more space: Polders are being flooded, retention basins are being built, tributaries being carved out and filled-up canals dug free again.

The old seafaring nation now has even less residential land available. Yet the Dutch discovered that the flooded polders and artificial water basins offer more benefits than just a controlled channeling of excess water.

Trend and challenge of generation climate change

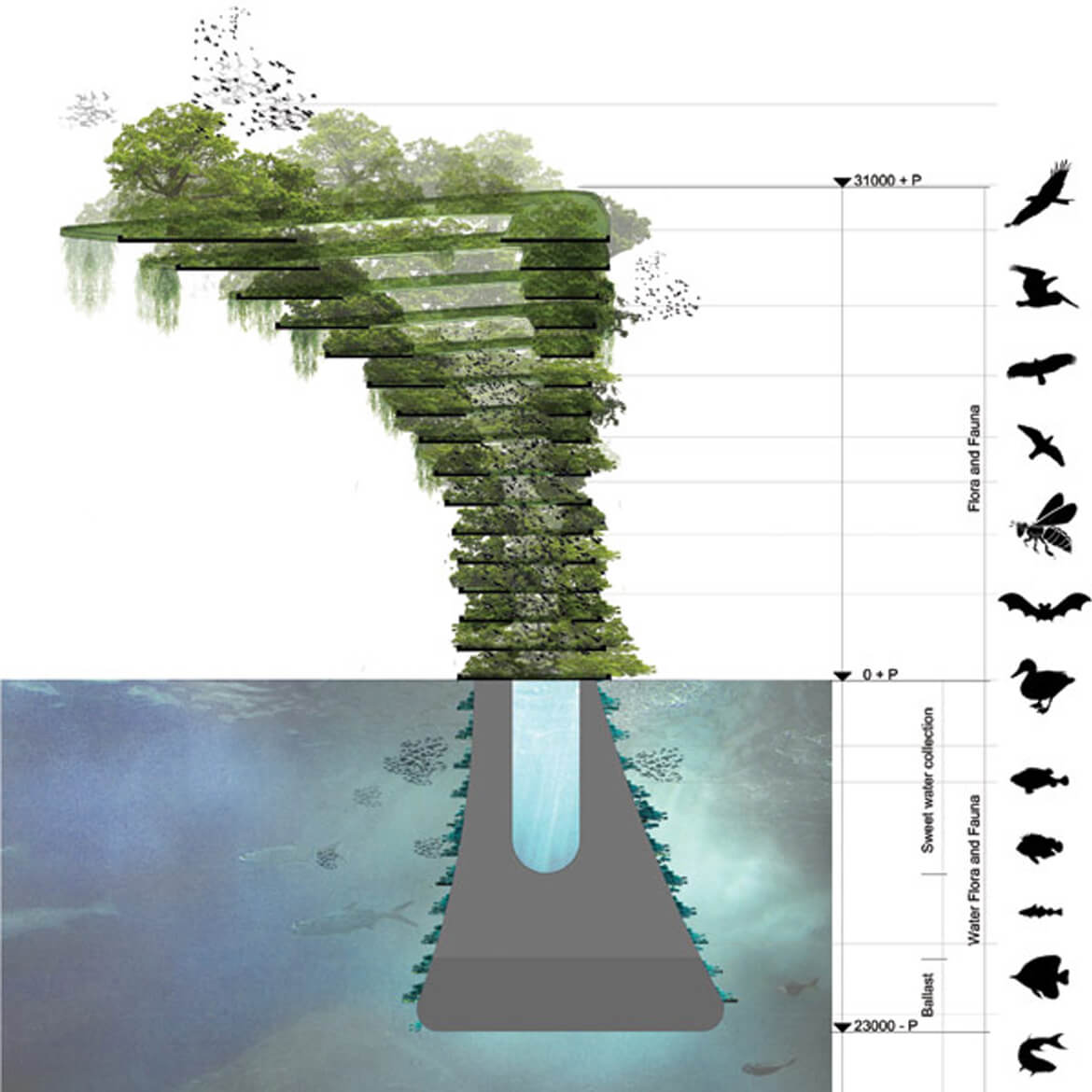

As a consequence, aqua living has since become a trend in the Netherlands; all over the country, people reside in what is called waterwoningen. Their foundation consists of a concrete tub filled with Styrofoam, which is considered unsinkable. To keep them in place, they are moored to poles with rings so they can easily adapt to rising sea levels. Electricity and water lines are connected via hoses and cables.

Olthuis has designed countless waterwoningen: transparent villas sitting elegantly on the water, such as in Aalsmeer, Zwolle, Leiden or Amsterdam, which received an entire floating neighborhood in 2012, the steigereiland. In Antwerp, Olthuis designed a floating boulevard on the Scheldt, in Paris he created a restaurant on the Seine. And in a polder between The Hague and Delft, he wants to build de Citadel, Europe’s first floating apartment complex on a foundation of 140 by 90 metres. “Technologically speaking, all of this is easy to do,” he stresses.

The technology developed and patented by Olthuis virtually eliminates size limits on foundations for waterwoningen. In other words, the foundation can be a platform large enough to accommodate entire blocks of houses, complete with yards and parking garages: “The larger an object, the more stable it is on the water,” the architect explains.

Olthuis is therefore convinced: The city of the future consists of floating platforms that can be moved around like floes of ice. “It will evolve one step at a time,” the bold Dutchman predicts: The next fifteen years will see churches, schools and sports fields move out onto the water, then in 50 years, we will have platforms as large as 200 by 200 metres, with houses, roads and parks – until a century from now, the city of the future will be a reality: a flexible delta-metropolis of floating elements. For Olthuis, this new type of urban design, this new flexibility is “the great challenge for the architects of the climate change generation.”

By Tanja Lina

By Tanja Lina

Hi Europe

Hi Europe

Med hjälp av cityappar vill arkitekterna på Waterstudio tillgodose grundläggande behov i världens vattennära slumområden. Foto: Sebastian van Baalen

Med hjälp av cityappar vill arkitekterna på Waterstudio tillgodose grundläggande behov i världens vattennära slumområden. Foto: Sebastian van Baalen