Testing the Waters: Floating home development in Florida

By Amy Martinez

Florida Trend

February.2015

A 2013 U.S. Supreme Court ruling could lead to a first-of-its-kind floating home development in south Florida.

(Amy Martinez)

In 2005, Hurricane Wilma destroyed a pair of dilapidated marinas in North Bay Village where Fane Lozman, a former Marine pilot and software developer, kept a two-story floating home.

The Category 3 storm struck from the south, scattering splintered docks and other large debris into more than a dozen neighboring floating homes.

For years, Lozman had relished the camaraderie and convenience of living on Biscayne Bay, especially the easy access to deep-sea diving and fishing and his favorite Miami Beach restaurants. “Your speedboat was tied up right outside your front door. And you could enjoy the south Florida water lifestyle immediately and at any time,” he says.

After Lozman’s floating home, which had been docked at the north end of the marina community, emerged relatively unscathed, he quickly began looking for another place to anchor. In 2006, he had his home towed 70 miles north to Riviera Beach and rented a slip at a city-owned marina.

His new neighbors told him not to get too comfortable, however, because a planned, $2.4-billion marina redevelopment project soon would displace them. Lozman sued Riviera Beach to stop the project. And that led to another dispute, which eventually wound up before the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 2009, after failing to evict Lozman in state court, Riviera Beach went to federal court, seeking a lien for about $3,000 in dockage fees and nominal trespass damages.

The city argued that because Lozman’s floating home could move across water, it was a vessel under U. S. maritime law. A federal judge in Fort Lauderdale agreed, and the home was seized, sold at auction and destroyed by Riviera Beach, which cast the winning bid.

Lozman countered that his home was similar to an ordinary landbased house and should have been protected from seizure under state law. The home consisted of a 60-by- 12-foot plywood structure built on a floating platform — with no motor or steering — and could move only under tow.

Lozman’s appeal caught the Supreme Court’s eye. And in early 2013, it handed him a victory. Justice Stephen Breyer wrote in the majority opinion that because Lozman could not “easily escape liability by sailing away” and because he faced no “special sea dangers,” his home was not a vessel and not subject to seizure under maritime law. Lozman is still seeking compensation from Riviera Beach for his home’s destruction.

After the Supreme Court’s ruling, Kerri Barsh, a Greenberg Traurig attorney who helped argue Lozman’s case on appeal, contacted Netherlands-based Dutch Docklands, a developer of floating homes.

Founded in 2005 by architect Koen Olthuis and hotel developer Paul van de Camp, Dutch Docklands had designed hundreds of floating homes in Holland and was looking to expand to the United States. Barsh believed the high-court ruling created an opening for the company to pursue a first-of-its-kind floating home development in south Florida.

It meant, for example, that buyers could get a mortgage and homeowners insurance, though they’d also have to pay property taxes. The Coast Guard couldn’t enter their homes to inspect for life jackets and other safety measures — and “if a gardener or maid is injured on your property, you don’t have to comply with strict workers’ comp standards,” she says. “You also may be entitled to a homestead exemption.”

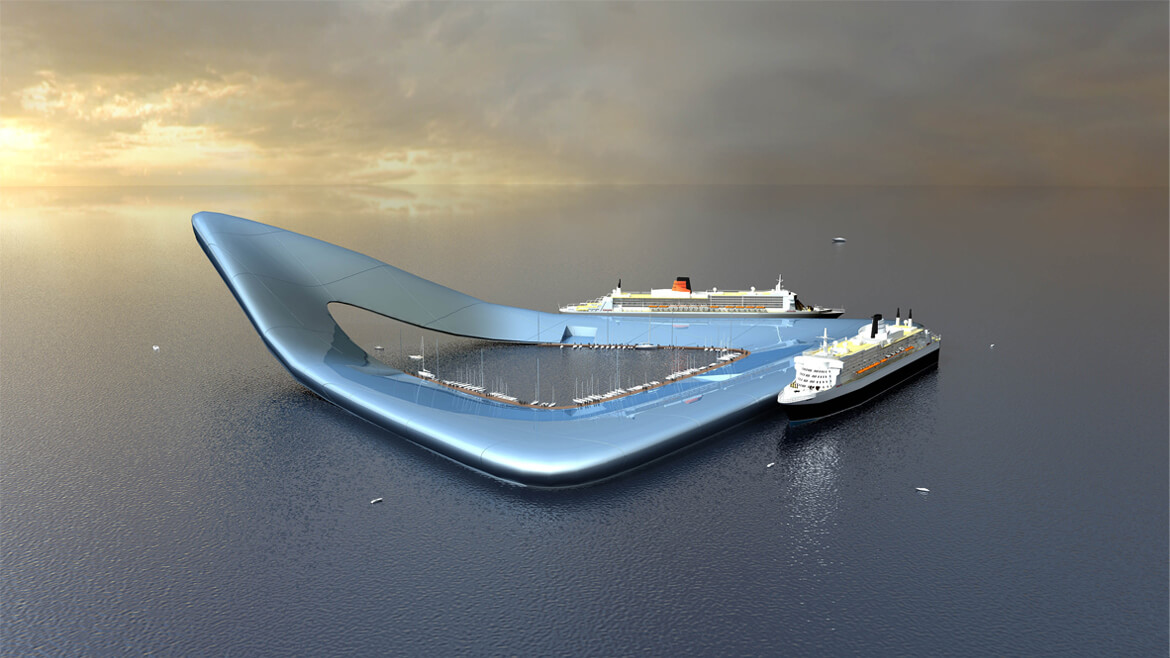

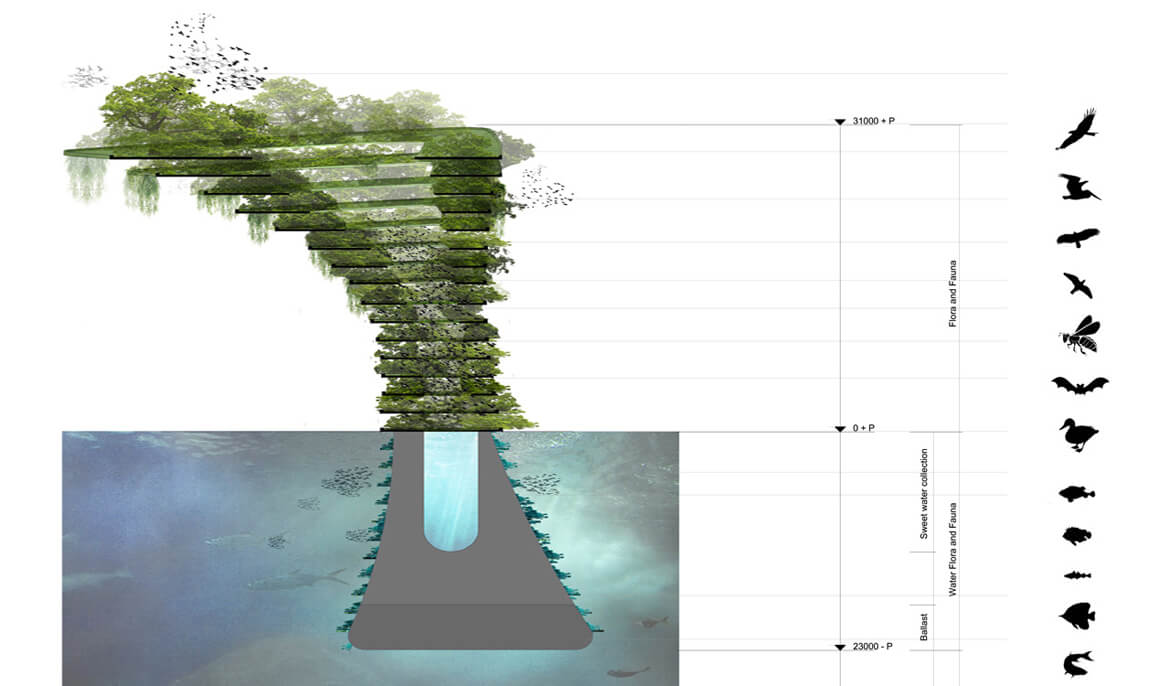

Dutch Docklands now is proposing a collection of multimilliondollar floating homes at a privately owned lake in North Miami Beach. Plans call for 29 man-made, private islands that are attached to the lake bottom with telescopic piles to guarantee stability.

Each island would cost an estimated $15 million and include a 7,000-sq.-ft. home, infinity pool, sandy beach and boat dockage, plus access to a 30th “amenity” island with clubhouse. The target market is celebrities and wealthy foreigners who want both privacy and proximity to downtown Miami, says Frank Behrens, a Miami-based executive vice president at Dutch Docklands.

“Buying your own island is a very complex process, and yet it’s a dream a lot of people aspire to,” he says. “Basically, what we’re offering is a way to realize that dream. Within two minutes, you can be on land and go to a Heat game or fancy restaurant.”

Historically, floating homes have not been widely embraced in Florida. A case in point is Key West’s Houseboat Row, which started in the 1950s as a playground for the rich, but in the 1970s deteriorated into floating shacks and live-aboards. In the 1990s, then-Mayor Dennis Wardlow repeatedly criticized Houseboat Row as an eyesore and environmental hazard. And by 2002, the community’s residents had been evicted and moved to a city-owned marina at Garrison Bight.

Today, the city marina has 35 floating homes and won’t accept any more. “We prefer to take in a registered marine vessel that’s Coast Guard certified,” says marina supervisor David Hawthorne. “Most marinas have moved out of it because of the liability, and there’s just more money in” short-term boat rentals.

To succeed in Florida, Dutch Docklands will have to change perceptions. The company promotes its brand of floating homes as a response to rising sea levels and climate change. And south Florida — as ground zero for sea level rise — could prove a receptive audience. Because of how they’re anchored, the floating homes move vertically with the tides, but not horizontally, enabling them to adapt to longterm climate changes and also hold steady in storms, Behrens says.

He hopes to begin construction next year at Maule Lake, a former limestone rock quarry with direct access to the Intracoastal Waterway. But his plans may be optimistic. The company recently filed for zoning approval and still faces questions about environmental impacts, the homes’ ability to withstand hurricanes and visual effects on the surrounding community.

“One of the big struggles we’ve had in this state is coming to grips with the fact that there’s a finite amount of land and water,” says Richard Grosso, a land-use and environmental law professor at Nova Southeastern University. “We tend to not recognize the importance of open space — the aesthetic and psychological value of it.”

Condominium towers — some pricier than others — surround Maule Lake. Behrens says local residents are understandably concerned about the project.

“If all of a sudden, a foreign developer comes and says, ‘Hey, we’re going to build private islands on this lake,’ I’d be upset, too,” he says. “But if you live in a $200,000 condo, and you get a $15-million private island on the lake in front of you, where a celebrity lives, you can imagine that the value of your real estate will go up.”

Even if all goes as planned for Dutch Docklands, it’s unlikely to spark copycat projects throughout Florida. Maule Lake presents “a pretty unique set of circumstances,” says Miami environmental lawyer Howard Nelson. At 174 acres, it’s big enough to accommodate a floating development without blocking boats — “and there’s very few bodies of water where the submerged land is privately owned,” says the Bilzin Sumberg attorney.

Meanwhile, Lozman has bought 29 acres of submerged land on the western shore of Singer Island in Palm Beach County. He says he’s talking with developers about building his own floating home community.

“I could see maybe 30 floating homes out there one day,” he says. “It would essentially duplicate the North Bay Village community that was destroyed in Wilma.”