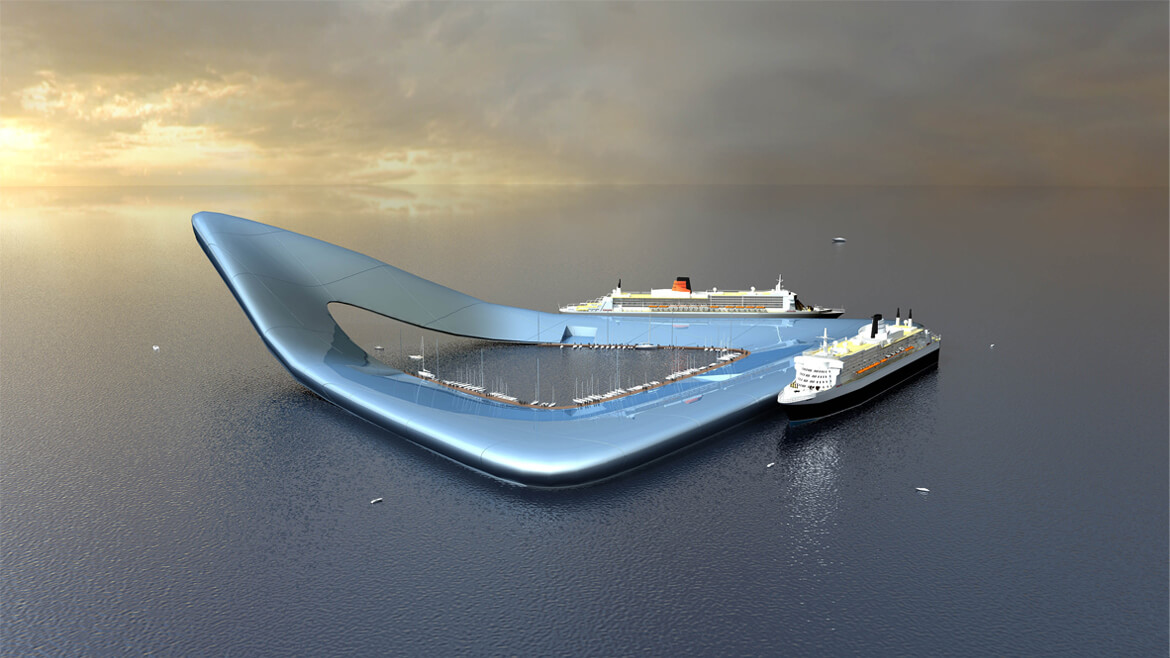

Floating Sea Wall one of 365 top initiatives of 2015

Waterstudio’s Floating Sea Wall is choosen as one of the 365 initiatives in 2015 that will reinvent our world.

Het conflict van de dynamische mens met statische steden en gebouwen

By Tanny de Nooy

Blandlord

July.1.2016

1 Juli 2016 Blandlord

Vastgoed móet flexibiliteit gaan bieden

Koen Olthuis studeerde Architectuur en Industrieel Ontwerp aan de TU Delft. Hij werkt sindsdien als architect en heeft water als specialisme. In 2007 noemde Time Magazine hem in de lijst ‘most influential people’ vanwege zijn werk in het wereldwijd groeiende interesseveld waterontwikkeling. Het Franse tijdschrift Terra Eco verkoos hem in 2011 tot een van de honderd ‘groene’ mensen die de wereld zullen veranderen. Olthuis’ architectenbureau Waterstudio en is gevestigd in Rijswijk.

“In Nederland kennen we als geen ander de mogelijkheid om van water bouwgrond te maken. We hebben een lange historie als het gaat om het bewoonbaar maken van natte gebieden. Dat fascineert me al sinds ik studeerde.” Koen Olthuis houdt zich al vijftien jaar bezig met architectuur op het water. In 2003 richtte hij Architectenbureau Waterstudio op en sindsdien is het bureau alleen maar gegroeid. Olthuis is een veelgevraagd architect, van China en Dubai tot aan de Oekraïne en de Malediven.

Olthuis is overtuigd van de vele kansen die water te bieden heeft als het gaat om te toekomst van vastgoed. “Waar het water vroeger nog benaderd werd als een vijand die in toom gehouden moest worden, is het de afgelopen twintig jaar een vriend geworden, die ongekende mogelijkheden biedt: we kunnen met z’n allen op het water gaan wonen! En ja: dat kan overal ter wereld. Van woonboten en waterwoningen tot drijvende resorts: als er water is, kun je erop bouwen.”

“Ik weet zeker dat de vastgoedwereld de komende jaren enorm gaat veranderen”, zegt Olthuis. “Kijk om je heen; de wereld is vandaag écht anders georganiseerd dan tien jaar geleden en dit is nog maar het begin! Bedrijven veranderen de manier waarop ze werken onder invloed van de mogelijkheden van internet en nieuwe technologieën en ook in onze privélevens veranderen onze behoeften onder invloed van deze ontwikkelingen. Je kunt op je vingers natellen dat wat wij verwachten van de fysieke ruimtes waarin we wonen en werken óók zal veranderen.”

De wereld om ons heen verandert

Olthuis wijst op de grote leegstand van kantoorgebouwen die zich het afgelopen decennium in veel steden ontwikkeld heeft. Hij verklaart die leegstand door de luiheid en traagheid van de vastgoedwereld. “Onze steden zijn statisch, onze gebouwen zijn statisch, maar wij, de mensen die er gebruik van maken zijn dynamisch. Je kunt de prachtigste gebouwen maken, maar omdat de wereld om ons heen zo snel verandert is dat gebouw over tien jaar al achterhaald. Als we op deze manier blijven werken zal er niets veranderen. Gebouwen die we nu ontwerpen zullen niet meer voldoen aan de dan geldende wensen en behoeften als ze gerealiseerd zijn. Vastgoed zal meer flexibiliteit moeten gaan bieden.”

“Er zijn zoveel veranderingen dat je die als architect onmogelijk allemaal kunt voorzien”, stelt Olthuis nuchter vast. “En dus is flexibiliteit bieden het enige wat je kunt doen. Vastgoed zou niet statisch moeten zijn. Vastgoed evolueert. Nu bouwen we gebouwen die zo lang staan dat ze overbodig worden en een negatief effect op steden hebben. Architecten moeten gaan ontwerpen voor verandering. We moeten gebouwen ontwerpen die snel en eenvoudig aanpasbaar zijn, zodat ze mee kunnen golven met onze veranderende wensen.” Dat meegolven mag je van Olthuis vrij letterlijk nemen: “Alles wat je op water bouwt is makkelijk aanpasbaar. Je kunt elementen snel verbinden met elkaar en je kunt andere dingen wegschuiven. Maar ook kartonbouw en panden die bestaan uit een lichte houtstructuur, piepschuim of containers zijn oplossingen die veel meer passen bij de wensen en behoeften van deze tijd. Nog geen twintig jaar geleden spuugden we erop, maar nu zien we de logica ervan in. Het biedt precies díe flexibiliteit die de vastgoedsector nodig heeft.”

Flexibiliteit is de sleutel

En flexibiliteit is ook precies wat bouwen op het water te bieden heeft, weet Olthuis. Als het aan hem ligt bouwen we over tien jaar hele steden op het water zoals dat in andere landen al lang gebeurt. “Denk bijvoorbeeld aan de RAI in Amsterdam. In feite is dat een ontzettend log gebouw, dat voor veel events die er worden georganiseerd nét te klein of veel te groot is. Ik kan me voorstellen dat je zegt: ‘we slopen de RAI en bouwen woningen op die gewilde plaats in de stad’. Met het geld dat dat oplevert zouden er drijvende expositieruimtes in de Amsterdamse havens gebouwd kunnen worden. Daar is immers plek zat! Bij een groot event laat je die nieuwe ruimtes naar een plek in hartje centrum drijven. Op die manier benut je de ruimte die je ook echt nodig hebt.” Olthuis droomt van een dynamische stad met flexibele gebouwen.“De ziel van zo’n stad wordt bepaald door vaste iconische gebouwen als kerken en universiteiten. Maar daaromheen bouwen we flexibele en verplaatsbare functies die gedurende hun levensduur niet meer perse locatiegebonden zijn. Helemaal ingespeeld op wat de gebruiker van het gebouw op dat moment nodig heeft.”

Het aantrekken van de economie en daarmee de woningmarkt is voor Olthuis hét moment om op te roepen tot meer innovatie in de vastgoedsector. “Juist nu het weer beter gaat moeten we in durven zetten op verandering. Als we blijven doen wat we altijd al deden zullen we vroeg of laat weer tegen dezelfde problemen aanlopen. Als we met behulp van de nieuwe technologieën die we nu voorhanden hebben durven te werken, plukken we daar al heel snel de vruchten van.” De kern van Olthuis’ verhaal? “Denk na over hoe we kunnen bouwen voor ‘change’. Wat er over 10 jaar gaat gebeuren weten we niet. Bouw dus met een kortere levensduur. Van nieuwe, slimme manieren van investeren en financieren tot het durven gebruiken van nieuwe bouwmaterialen: gebouwen moeten weer van en voor de mensen zijn. Dát is de toekomst.”

These next-level underwater villas are making waves

By Kate Springer

CNN

July.11.2016

Citadel, Westland

An ambitious project from Dutch developers ONW/BNG GO, the Citadel is Europe’s first floating apartment building. It’s part of the New Water development project, which will comprise six floating apartment buildings — all designed to adapt to flooding and rising water levels.

Dubai is still waiting for its floating mosque

By Neil Churchill

EDGAR daily.com

june.26.2016

UAE residents could pray at sea should a new developer take up the project.

Heard the one about Dubai’s underwater hotel? Of course, everybody’s heard that urban myth. But what about Dubai’s floating mosque?

Yes Dubai, not so long ago, had plans to build a mosque out at sea. In fact it was due to be completed only in March last year, with these renderings showing what it would have looked like. Judging by the images, it may have made our list of the 10 most beautiful mosques around the world.

But the local developer put the plans on hold, and the floating place of prayer never left the drawing board.

The sustainable mosque was designed by Waterstudio, a Dutch architecture firm specialising in water-based projects, and was being prepared for its client Dutch Docklands International, a Dubai-based company that also specialises in on-sea developments.

But even though the initial plan was shelved the floating mosque dream is not yet over, with the blueprints still available to be used.

“It is still on the drawing board. We are waiting for a new client to bring this project to life,” said Koen Olthuis, principal architect at Waterstudio, speaking to EDGAR.

“It was first designed for Palm Jebel Ali but when that project was put on hold by Nakheel we had to search for a new location and client. There has been a lot of interest in this project by the media and developers, but not a definitive signature yet.”

Olthuis gave a breath of oxygen to the project, suggesting it hasn’t been dismissed and that he is waiting for “the perfect user for this sustainable and water-cooled floating mosque”.

Should a new developer take up the project, the plans show that the interior of the mosque would feature several funnel-shaped, transparent columns that would not only support the roof but also allow in natural light to illuminate the inside. There would also be an open air courtyard area.

With the UAE’s history of fishing and pearl diving, it would be one of the more nostalgic modern projects the country has seen. Following the design of the Dubai Opera building, which resembles a traditional dhow, maybe this is the direction UAE architecture is heading; taking inspiration from its past.

Flotter vers Léau-dela

By Gabrielle Anctill

Esquisses

2016 volume 27 nr 1

Projets exemplaires

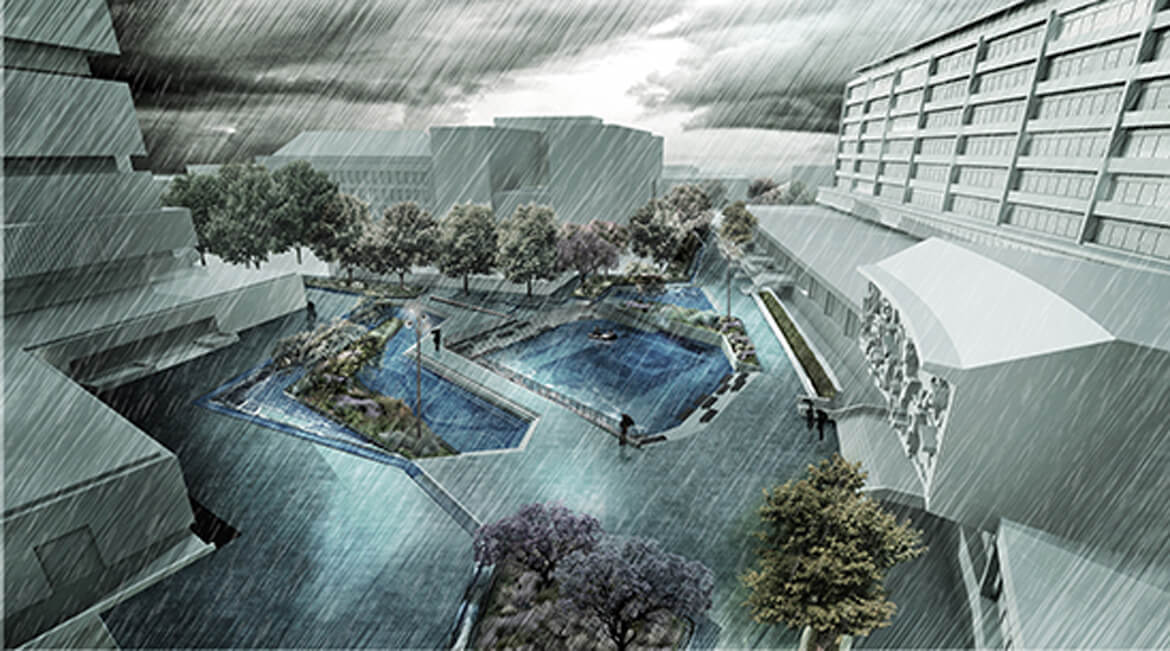

Carré d’eau

Waterplein (square d’eau), Rotterdam (Pays-Bas), De Urbanisten. Illustration: De Urbanisten

L’ennemi des villes de demain sera l’eau. En première ligne, Rotterdam aux Pays-Bas, qui doit se préparer à combattre les pluies torrentielles causées par les changements climatiques. Pour vaincre les flots, une arme : la place publique.

Gabrielle Anctil

Plutôt qu’une catastrophe à prévenir, la Ville de Rotterdam a décidé de voir les changements climatiques comme une occasion à saisir. C’est pourquoi elle a mandaté en 2005 la firme de recherche urbaine et de design De Urbanisten pour trouver des solutions novatrices en matière de gestion de l’eau. De ces réflexions a émergé l’idée du waterplein ou « square d’eau », une place publique servant aussi de bassin de rétention des eaux.

« La mission du square est de réconcilier la population avec l’eau. Nous voulions créer la même magie que lorsqu’un enfant joue dans une flaque d’eau », explique Dirk Van Peijpe, ingénieur et cofondateur de la firme. Un premier spécimen, le Waterplein Benthemplein, a vu le jour en 2013. Composé de trois bassins de différentes profondeurs, le plus profond faisant office de terrain de basketball, il est conçu pour servir principalement d’espace public. La communauté, qui a participé pleinement à sa conception, se l’est rapidement approprié : en plus des sportifs et autres flâneurs, on peut même y croiser des fidèles assistant à un baptême, gracieuseté de l’église avoisinante.

Lors d’une averse, les trois bassins servent à stocker l’eau de pluie. Avec style. « Nous avons voulu mettre l’accent sur le design », précise Dirk Van Peijpe. Ainsi, les gouttières en acier inoxydable qui transportent l’eau depuis les bâtiments adjacents vers les bassins sont assez larges pour accueillir les planchistes par temps sec. D’autres détails permettent de contrôler la façon dont l’eau atteint les bassins, pour rendre le tout le plus spectaculaire possible. Une fois les égouts libérés, l’étang cède de nouveau l’espace à la place publique.

Le square d’eau est un concept qui porte ses fruits : la firme en planifie déjà un deuxième dans la ville de Tiel, toujours aux Pays-Bas. « La beauté du square, c’est que nous avons repris une idée simple : l’eau descend », souligne Dirk Van Peijpe. Comme quoi certaines idées novatrices coulent de source…

Soigner contre vents et marées

Hôpital Spaulding, Boston (États-Unis), Perkins + Will. Photo : Anton Grassl/Esto

Sous sa façade grise, l’hôpital Spaulding est comme Superman dans les habits de Clark Kent. Portrait d’un bâtiment prêt à tout.

Gabrielle Anctil

L’ouragan Katrina qui a frappé La Nouvelle-Orléans en 2005 a causé un choc dans le milieu hospitalier américain. « Le monde médical a vu les hôpitaux hors d’usage et s’est dit : plus jamais », se remémore Robin Guenther, architecte et associée principale chez Perkins + Will, une firme d’architecture américaine. Mais, lorsque l’ouragan Sandy est tombé sur New York sept ans plus tard, les télévisions ont encore une fois relayé les mêmes images.

C’est avec ces leçons en tête que l’architecte s’est attelée à la conception de l’hôpital Spaulding, à Boston. « Notre client était parfaitement conscient de ce qui s’était passé à La Nouvelle-Orléans et voulait construire un hôpital qui résisterait aux effets des changements climatiques », explique Robin Guenther. Situé dans le port, le bâtiment devait absolument être à l’épreuve de la hausse du niveau de l’eau. Une mission de taille, compliquée par la quantité de données avec lesquelles jongler. Élever le bâtiment était une évidence, mais quelle sera l’élévation du niveau de la mer dans 50 ans ? Comment composer en même temps avec les besoins d’accessibilité d’une clientèle à mobilité réduite ?

L’élévation du bâtiment n’est qu’une des multiples caractéristiques qui le préparent au pire : les génératrices sont situées sur le toit, plutôt qu’au sous-sol, emplacement inondable où on les trouve habituellement, les fenêtres peuvent s’ouvrir et la végétalisation des toitures contribue à réduire les îlots de chaleur.

Les architectes ont tenté de penser à tout, sans pour autant faire exploser les coûts. En fait, moins de 1 % du budget total a été consacré aux mesures d’adaptation aux changements climatiques. Pour Robin Guenther, c’est une évidence : « Quand on y réfléchit à l’avance, comme nous l’avons fait, les coûts sont minimes, alors que réaménager un bâtiment déjà construit coûte extrêmement cher. D’où l’importance de parer dès la conception à la prochaine tempête du siècle. »

Il semble bien que l’hôpital Spaulding sera prêt à l’affronter.

Les jardins suspendus de Milan

Bosco verticale (forêt verticale), Milan (Italie), Stefano Boeri. Photo: Paolo Rosselli.

Le rêve de l’empereur Nabuchodonosor II serait-il devenu réalité ? Devant la menace des changements climatiques, l’idée de verdir en hauteur comme à Babylone n’a plus rien de fantaisiste, tel que le démontre le projet Bosco verticale de Milan.

Gabrielle Anctil

En construisant à Milan les deux tours d’habitation du projet Bosco verticale (forêt verticale), l’architecte italien Stefano Boeri ne voulait pas que leur architecture soit uniquement ornementale. « Les bâtiments sont volontairement plutôt sobres, explique le concepteur. Ce qui compte le plus, c’est l’intégration de la nature. »

Les tours de Bosco verticale sont, comme leur nom l’indique, couvertes de végétation. Mais Stefano Boeri a vu plus loin que les toits verts que l’on connaît déjà : sur les balcons des bâtiments poussent de vrais arbres. « En fait, chaque habitant en a deux, plus huit arbrisseaux et 20 plantes. » Beaucoup plus original qu’une cour de banlieue, et surtout, bien plus durable. « Les villes doivent être plus denses, rappelle l’architecte. Nous ne pouvons plus nous permettre de maintenir le rêve de la maison de banlieue. »

Pour Stefano Boeri, la nature a un rôle primordial à jouer dans la lutte contre la pollution des villes. « Les arbres permettent d’absorber la poussière ambiante et le CO2, de minimiser l’impact des îlots de chaleur urbains et de réduire la température à l’intérieur des logements pendant l’été, réduisant du même coup la consommation d’électricité », énumère l’architecte. Une attention toute particulière a d’ailleurs été accordée au choix des arbres afin de maximiser leurs bienfaits. Ainsi, du côté nord, on a sélectionné des essences à feuilles caduques pour laisser le soleil réchauffer les logements en hiver.

Toute originale qu’elle soit, la forêt verticale doit pouvoir être reproduite à moindre coût pour avoir un réel impact. « Il est tout à fait possible de copier-coller l’idée n’importe où dans le monde, à condition de sélectionner des arbres adaptés au climat », affirme Stefano Boeri. L’architecte s’est d’ailleurs vu confier la mission de concevoir une ville de 100 000 habitants en Chine, selon le modèle de ses tours milanaises.

Si l’idée prend racine, les enfants de demain pourront peut-être grimper aux arbres… sur leur balcon.

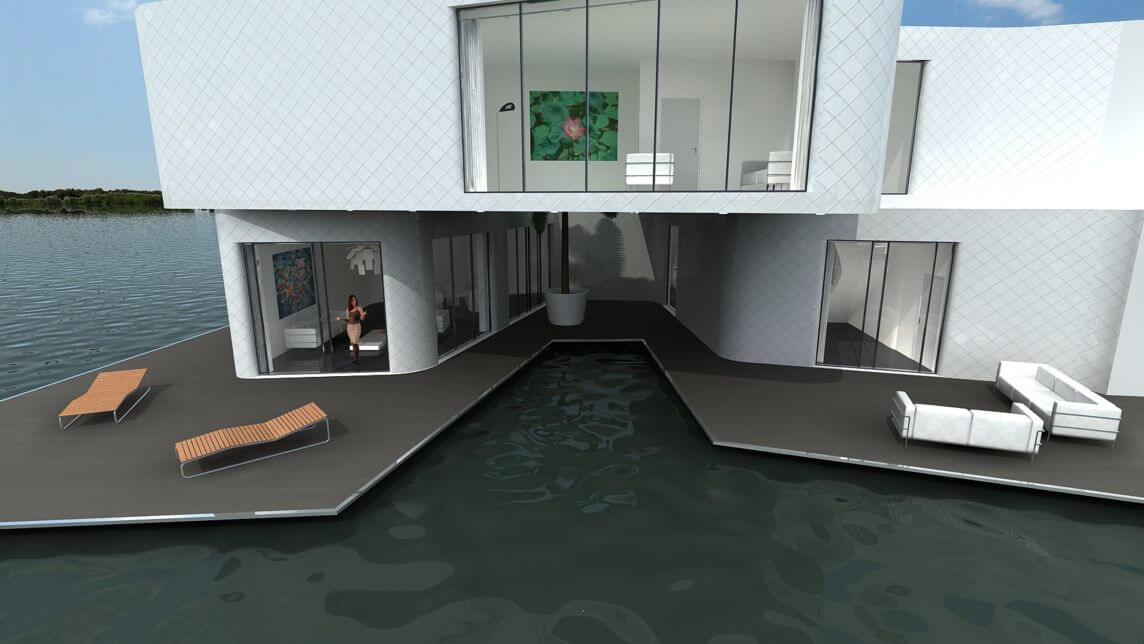

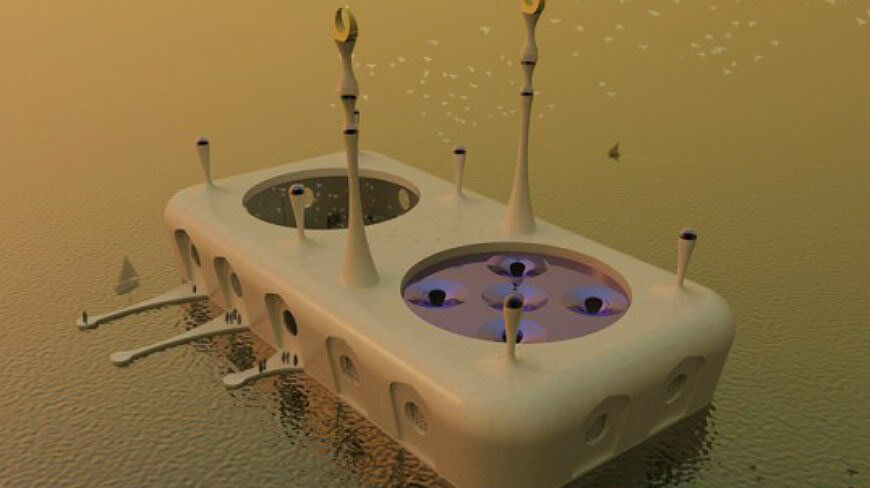

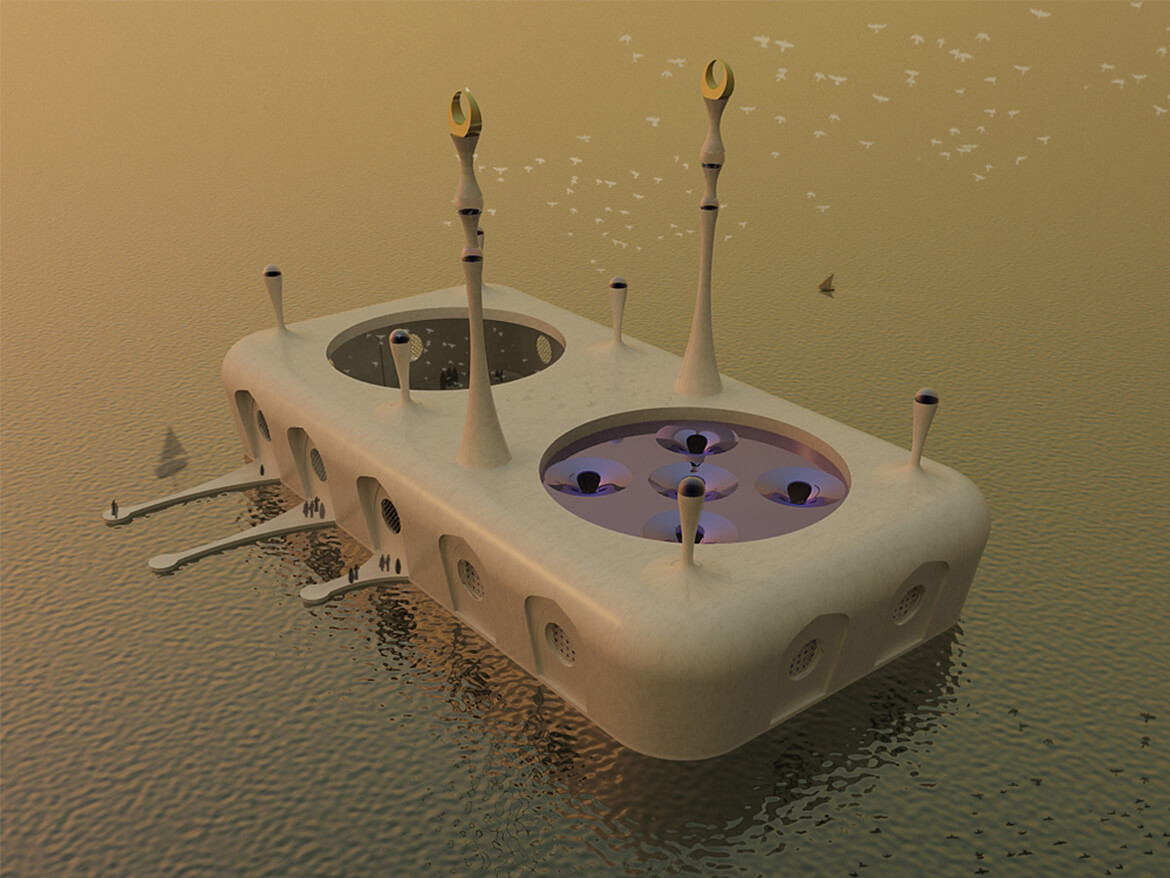

Flotter vers l’au-delà

Concept de mosquée flottante à Dubai (Émirats arabes unis), Koen Olthuis Waterstudio.NL. Illustration : Koen Olthuis – Waterstudio.NL et Dutch Docklands

Une mosquée flottante? L’idée peut sembler loufoque, voire sacrilège. Pourtant, ce type de construction est peut-être la solution idéale pour défier les inondations dans les villes de demain.

Gabrielle Anctil

La firme Waterstudio, de l’architecte néerlandais Koen Olthuis, ne construit que sur l’eau. Quand on lui demande pourquoi, le fondateur répond du tac au tac : « On est en sécurité sur l’eau. Plus besoin de s’inquiéter des inondations. » Pour étonnant qu’il soit, le concept n’a rien de nouveau. « Aux Pays-Bas, on construit sur l’eau depuis plus de 200 ans », affirme l’architecte.

Son expertise a mené Koen Olthuis à travailler à Dubai, aux Émirats arabes unis, où on lui a confié en 2007 le mandat de concevoir un lieu de prière inédit : une mosquée flottante. En plus d’avoir les deux pieds dans l’eau, le bâtiment utilise les flots comme système de climatisation. « En été, les températures montent jusqu’à 50 °C, mais l’eau reste toujours à environ 27 °C », explique l’architecte. L’eau est pompée à travers les murs et passe par le toit avant de retourner dans le golfe Persique, rafraîchissant l’air au passage.

Un bâtiment flottant ne pose-t-il pas des contraintes architecturales importantes ? « Pas du tout, affirme Koen Olthuis. Mise à part la fondation, qui doit s’adapter au type d’écosystème où on la placera, l’architecture est presque identique à celle d’un bâtiment traditionnel. » Le plus gros défi ? Changer la perception du public. À Dubai, l’idée d’une mosquée sur l’eau a causé des remous dans la communauté. « Il y avait des débats à la radio où on se demandait si la mosquée serait assez sacrée ! » se remémore l’architecte. La conclusion ? Oui, mais seulement si elle pointe toujours dans la direction de la Mecque.

Retardé par une économie vacillante, le projet ne verra peut-être jamais le jour. Mais si on en croit Koen Olthuis, les constructions flottantes sont la voie de l’avenir. « On peut construire presque n’importe quoi sur l’eau. Avec l’urbanisation accélérée et les coûts élevés des terrains dans les villes, l’idée de construire sur l’eau devient une évidence. » À quand un quartier flottant au Québec ?

Has Floating Architecture’s Moment Finally Arrived?

By Rachel Keeton

Next City

October.01.2014

Resilient Cities

The Sea Tree, a floating natural habitat. (Photo by Waterstudio)

In a quiet, shady street in Rijswijk, the Netherlands, Koen Olthuis and the design team at Waterstudio are changing the world. From this deceptively nondescript headquarters, Waterstudio is designing the cities of the future. If Olthuis has his way, they will be safer, more flexible and more resilient than current cities. How will he do this? Olthuis is designing floating cities. As we sit down at the table, the busy office buzzing around us, my first question to Olthuis is direct: “How realistic are floating cities?” Olthuis grins and nods, he’s heard this question before.

Floating cities have captivated society’s imagination for centuries, from the development of Venice a millennium ago to Triton, designed for Tokyo Bay by Buckminster Fuller in the 1960s. But it wasn’t until the last decade or so that more fully realized, just-might-actually-happen sea-based urban endeavors have emerged, made more urgent by rising sea levels and rural-to-urban migration. In the last six months, Business Insider, Bloomberg and The Guardian have all run stories asking the same question: “Has the time come for floating cities?”

Olthuis dives right in: “It depends what you mean by ‘floating city.’ If you’re talking about a community of 100,000 in the middle of the sea, we’re probably about 50 years away from achieving that. If you want it to be completely self-supporting, it’s probably going to take another 20 years after that.” Bending over a roll of tracing paper, Olthuis quickly sketches a timeline of floating architecture. If we take it from the present moment, about midway on Olthuis’ sketch, hybrid cities are the next step in this evolution. Built on the edge of the existing city, these developments could easily connect to electrical and sanitation grids. “Technically, this stuff is easy to engineer: we’re already there,” says Olthuis. That makes them more straightforward to regulate and less risky for investors.

It’s the images of sparkling new cities lost at sea that have people raising skeptical eyebrows. “We’re working on a set of guidelines, a toolbox that will ultimately get us to the floating city you imagine. We’re working out these concepts that all give a glimpse of the future, but we have to find out what we need, how it works and what it adds to current urban development. We have to map out the steps to get us from today to the future and have to think about the entire process. And we need that, because if we don’t answer these questions, we get all these architects with beautiful renderings and fantastic ideas, but they don’t tell you the steps in-between and they don’t tell you why. And then your question is, but how realistic is it?”

Listening to Olthuis, it quickly becomes apparent that this scenario is actually incredibly realistic. With the technology and market demand in place, it’s political will and ownership issues that are holding development back. People have trouble imagining an urban future where city halls can be swapped for theaters on opening night, or entire Olympic villages can simply be towed around the world instead of rebuilt every four years. “Our cities today are too static. We make static cities for dynamic societies. We should be cities that can adapt to new demands and external influences. Water gives us three things: it adds more space (in old harbors, rivers, lakes), it’s safer (from storm conditions, rising sea levels) and it’s flexible. If you only construct the buildings you will use for 100 years statically, on land, and construct the buildings you will only use for 20 to 30 years flexibly, on water, then you’ve created a much more adaptable city that can respond to changing needs quickly and efficiently. If someone isn’t happy with their house anymore, they can ship it to someone who needs it in the Philippines.”

Governments are slowing starting to see the potential of this approach. If cities like New York or Tokyo build two to three percent of their development on the water, they can sell this to developers, tax the owners and create a more flexible city. Win-win. Governments are interested in this because it presents a new market for them. While most land is privately owned or already built up, by changing policies to make floating structures available the government expands its real estate. It’s a business model that is attractive because it solves multiple problems. Floating structures can reinvigorate former industrial areas like old harbors or riversides, they can adapt to extreme weather conditions better than traditional structures and they create a profit from space that is currently unmarketable.

Still, the idea of bobbing around permanently makes some people understandably squeamish. If one floating house goes up and down on waves, it may tilt: one half sits on the crest of a wave and the other end is stuck in the trough. This doesn’t happen when you start to build big enough to have a project that is always supported by multiple waves. On the water, the bigger the project, the more stable is it. In fact, floating cities are actually something that works better all around on a larger scale. If Olthuis is designing a watervilla for a single family, he has to calculate all kinds of factors to design a single, site-specific home. This ends up costing a lot more than a traditional house. If he’s designing a community of 10,000 water villas, the price is the same as a comparable urban development.

Moving functional amenities like prisons, stadiums and airports onto the water is already becoming more common as cities try to create more elbowroom for residents. Alvaro Siza’s recently completed chemical plant in Huai’An City, China, was built on the water, and BREAD Studio recently designed a floating cemetery to be rafted off the coast of Hong Kong – a city long on elderly citizens but short on space. Today there’s a floating skate park on Lake Tahoe and floating freshwater pools in the River Thames. There’s even a floating cinema in London by UP Projects, echoing Aldo Rossi’s iconic Il Teatro del Mundo from 1979.

Less whimsical but more crucial are floating developments for informal settlements located on waterfronts or in delta regions that are most vulnerable to rising sea levels. Kunlé Adeyemi’s floating school in Makoko, a picturesque shantytown in Lagos, Nigeria, will provide classroom space for 100 students. The problem with one-off projects like NLE’s floating school, according to Olthuis, is that the Lagos government has been against it from the beginning (it’s been declared illegal), and it’s not even being used because of this controversy. “If you want to really make a difference, it can’t be just one thing. It has to be a system with a sound business model,” says Olthuis.

“I think the current generation of architects really wants to help, they want to make a difference. If you tell the story of one billion people living in slums in places like Thailand, India, Bangladesh — where water is threatening those people and no one is helping them because anything that gets built can be wiped out by the next tsunami — we think, well we have to help those people. The City Apps project — retrofitted shipping containers floating on trash — is a system where we bring in floating schools, sanitation, electricity, water treatment facilities, bakeries, internet cafes, or whatever is most needed. We can connect these floating functions to the slums or disaster sites and they will slowly help upgrade these areas.

We’re investing in this ourselves, by funding the first prototype that will be deployed to Manila. We’ve started a foundation, working with Cordaid, where we lease the City Apps directly. It costs us about €50,000 to design and build a City App in a recycled shipping container, then it gets deployed to wherever it’s needed and there they construct a floating platform out of old plastic bottles and other rubbish. Ultimately, it should be a business model that provides an entrepreneurial opportunity for residents of these areas. It’s cheap — they just pay a small monthly fee — it’s safe, since it goes up and down with the water, and it provides a solution to real problems. If you don’t need it anymore, you just send it back to us and we lease it out to someone else. Next year we’ll have ten, the year after, a hundred, and it will grow to a few thousand containers around the world. Of course, it’s just a small help to these millions of people, but we hope it will act as a model and show that we can shift from giving aid to providing an opportunity for employment.”

On the other end of the inclusiveness spectrum, there are politically motivated projects like the Seasteading Institute’s Floating City. Promoted with viral videos and backed by private donors and crowd funding, these mobile communities are envisioned as new experiments in governance, giving each community total political autonomy over itself. After attending the third Seasteading Institute conference in 2012, Josh Harkinson of Mother Jones summarized the Institute as “a hacker’s approach to government with a Waterworld-esque conception of Manifest Destiny. More than a mere repository for political dreamers, it brings together engineers, scientists, and entrepreneurs of the sort one often finds in the Bay Area: techtopians who might be brilliant or delusional — or both.”

Olthuis accepts that different floating communities may have different goals. “I think we’ve only seen about 10 percent of the ideas that are actually possible in terms of floating architecture. In the next century, we’ll have thousands and thousands of new architects who can think about these possibilities.” Waterstudio calls their floating designs “scarless,” meaning they can be repositioned without leaving any trace of their presence. But the next step is to build designs like the Sea Tree, a floating natural habitat that would give small fish a sanctuary, increase the oxygenation of water, and potentially collect trash as it drifted about.

Olthuis is adamant that we have to embrace the water rather than run from it — we don’t have any other options. “Today, the momentum is there because we see the effects of climate change and we can’t be sure about our safety. We see millions of people moving to the cities and we don’t know where they will live. These issues are finally making people think twice about floating architecture. If we can convince them that it’s also financially profitable and help governments change building regulations, we’ll have a future where it’s normal to see cities that are 95 percent built on land and five percent built on water — just enough to give them the flexibility they need for an uncertain future.” It’s a revolutionary way of thinking about the city: puzzle pieces that can be reconfigured according to changing needs and desires. Olthuis’ concern with marketability and political interest makes his story much more convincing than the glossy renderings popping up on design websites. “Many architects are using technical solutions to approach this problem and just showing us the images without any information. I think a floating city is only something that works when it makes sense economically, socially, spatially — and should also look nice. It should be a normal development that is open to everyone, rather than an alien form for an elite few.” His belief in the advantages of these projects is clear, and the built examples in the Maldives, China and the Netherlands are proof of their viability. Just as it was for Buckminster Fuller 50 years ago, the floating city remains an exciting and mysterious model of urban development. Only now, it’s closer than ever. And Koen Olthuis can tell you exactly how to build it.